Ep. 42 - Awakening from the Meaning Crisis - Intelligence, Rationality, and Wisdom

(Sectioning and transcripts made by MeaningCrisis.co)

A Kind Donation

Transcript

Welcome back to Awakening from the Meaning Crisis. So last time, we were taking an in-depth look at the work of Stanovich and rationality, 'cause we are building towards an account of wisdom. Because that is deeply intertwined with the cultivation of enlightenment and, of course, with the cultivation of meaning.

We noted that rationality is an existential issue. It's not just a matter of how we're processing information. It's something that is constitutive of our identity in important ways and our mode of being in the world. And we'll come back to that again.

One of the core things we saw as we took a look at the rationality debate in which Stanovich's work is situated, is that debate showed us a couple of important things. It showed us if I can put this as a formula that rationality does not equal logicality and it does not equal intelligence (Fig. 1) (Writes Intelligence ≠ rationality ≠ logicality). That debate also showed us that we need multiple competencies when we're talking about rationality. We need an inferential competency, but we need an independent competency of construal. And then I proposed to you how we could understand what that competency is and what the normative theory is acting upon it. Namely insight, good problem formulation.

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

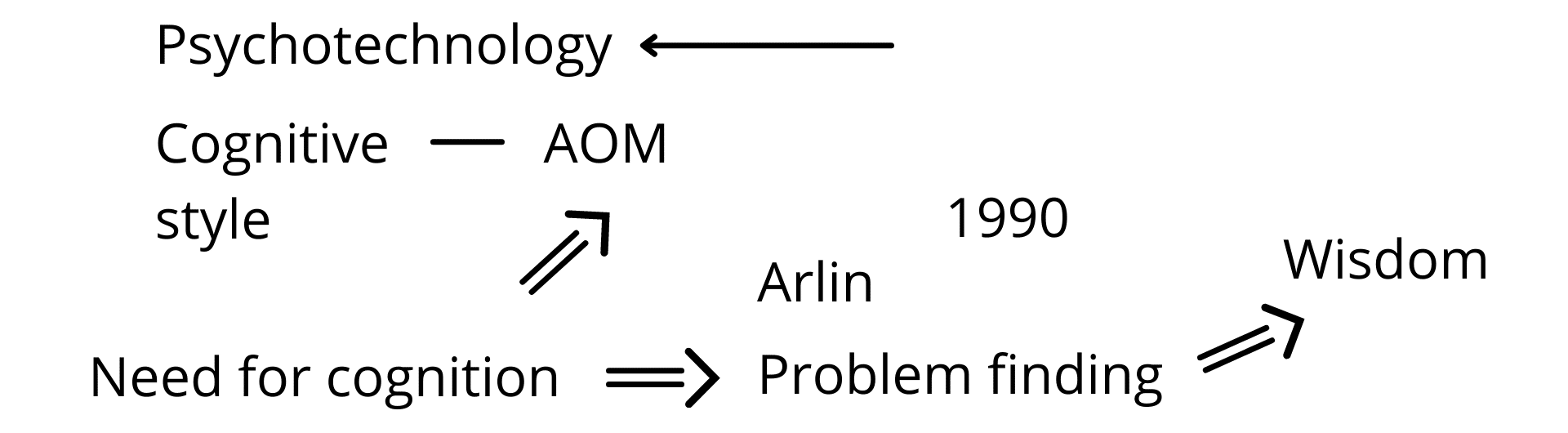

We then moved into what Stanovich saw as the missing piece. If intelligence doesn't give us rationality, what's the missing piece? There's two missing pieces. They overlap in some important ways. One is the notion he calls it mindware, what I've called psychotechnology (Fig. 2a) (writes Psychotechnology) and the other is a cognitive style (writes Cognitive below Psychotechnology). And the cognitive style that he talked about was active open-mindedness (writes AOM beside Cognitive), which he gets from Jonathan Baron. And this is the idea that what you should do is cultivate a sensitivity and an ongoing awareness of the presence and effect of cognitive biases in your cognitive behavior and your cognitive life, and to actively counteract them.

Fig. 2a

Fig. 2a

I pointed out that, unlike Stanovich, who doesn't emphasize this as much, Jonathan Baron, who's the originator of this idea (AOM) as a constitutive of feature of rationality points out that you can't do that too much. 'Cause if you try to override too many of your cognitive biases, you, of course, will be also overriding them in their functioning as heuristics, that help you avoid combinatorial explosion. So getting an optimal form of active open-mindedness rather than a maximum form of it is crucial to rationality.

Defining Psychotechnology

I want to just briefly stop here and be a little bit more precise about how I want to use this term (draws an arrow pointing to Psychotechnology). I've been using it throughout, and I basically defined it by example, and then through exemplification. But I want to be a little bit clear about it because it's going to be relevant as we go forward and talk about wisdom.

So here's the definition I want to offer to try and clarify what I mean and how I'm using the term psychotechnology. As I said, I don't claim to be the originator of this idea, but I am claiming that this is the particular slant I'm taking on this idea of psychotechnology. The psychotechnology is a socially generated and standardized way of formatting, manipulating, and enhancing information processing that's readily internalizable into human cognition, and that can be applied in a domain general manner. That's crucial. It must extend and empower cognition in some reliable and extensive manner and be highly generalizable among people. Prototypical instances are literacy, numeracy, and graphing.

So I want to just make it very clear. It's not just that anything we use mentally will count as a psychotechnology. So the cognitive style of active open-mindedness will probably make use of psychotechnologies in order to help track bias. But obviously, Stanovich means something much more comprehensive. He means a set of skills, psychotechnologies, sensibilities, and sensitivities that will help you in a domain general manner, note and actively respond to the presence of cognitive bias. We can then ask, what is it about people that if intelligence is insufficient for this (indicates Fig. 1), what is it about people that is predictive of them acquiring this (draws an arrow pointing to AOM). Now, this is learnable (indicates Psychotechnology), right?

Need For Cognition And Problem Finding

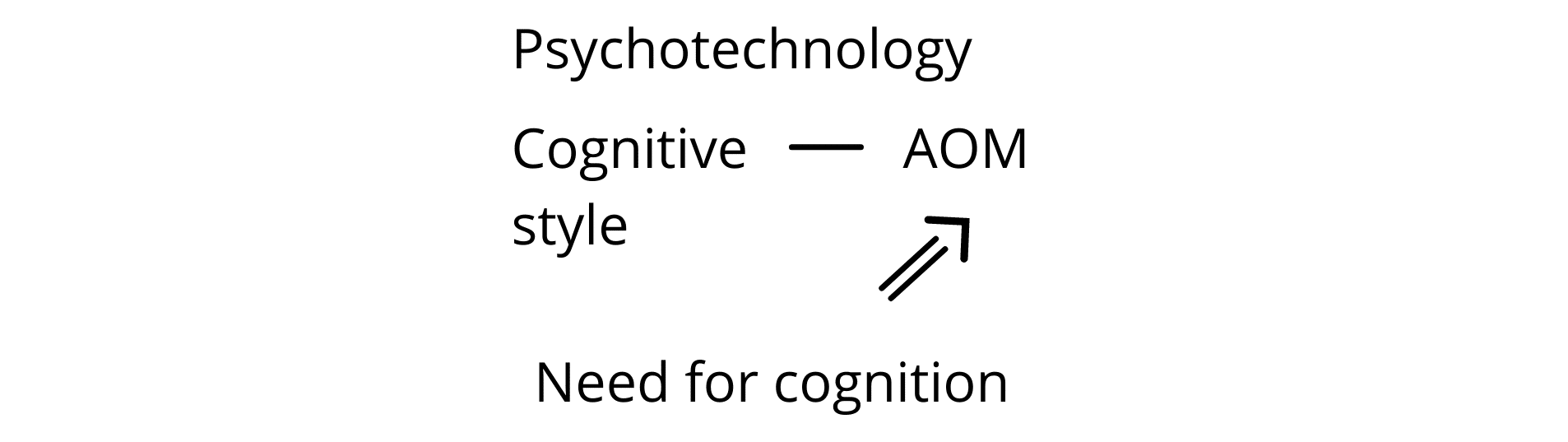

And we talked about the need for cognition as being an important predictor (Fig. 2b) (writes Need for cognition at the end of the arrow below AOM). So this is the degree to which you are motivated to go out and look for problems. You're trying to find, formulate, and solve problems. And so in that sense, you are generating your own instances of learning and problem solving in a quite directed and comprehensive manner. I suggested to you that there's two ways in which we can think about this curiosity and wisdom (Text overlay appears saying "John means "Curiosity and Wonder" instead of "Curiosity and Wisdom").

Fig. 2b

Fig. 2b

I want to stop here and note something about this need for cognition (draws an arrow from Need for cognition) that I'm now going to be making use of in today's lecture. Which is the connection between the need for cognition and what Arlin calls (writes Arlin), problem finding (Fig. 2c) (writes Problem finding below Arlin). Because that's a very central feature, I would think. I would say an essential feature of what it is to have a high need for cognition. Arlin argues that problem finders are very good at finding problems. As the name indicates there, they are able to realize problems and connect things together in ways that other people have not previously done. Some people have argued that this is central to creativity. But important for our purposes is that Arlin—and this is kind of prescient of this whole argument. She made this argument in 1990 (writes 1990 above Arlin). She argues that this is central to wisdom (draws an arrow pointing from Problem finding and writes Wisdom). That one of the crucial features of being a wise person is the capacity to find problems that other people have not yet found.

Fig. 2c

Fig. 2c

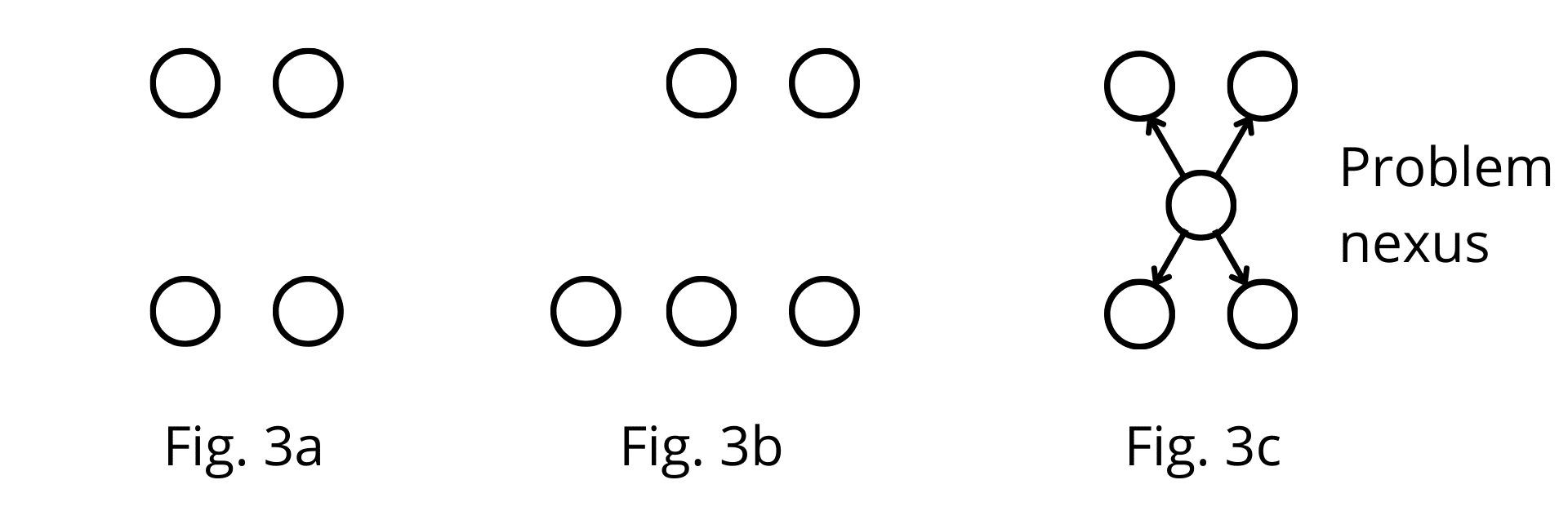

I want to take a moment here and offer a suggestion of how we can think about what makes somebody a good problem finder. I want to—this is not in Arlin, this is my attempt to extend, to develop Arlin and make it a little bit more concrete and practicable. So I want to propose to you this idea (erases the board).

Becoming A Good Problem Finder

We don't find problems typically in a vacuum. We don't do anything in a vacuum. There's always, you know, already a background of existing issues we're dealing with, other people are dealing with in our culture. I would suggest to you that a good problem finder can do this. Here's some existing problems in the space in which human beings are operating (Fig. 3a) (draws 4 circles). And what a good problem finder does is, I think, not just simply add to that (Fig. 3b) (draws a 5th circle). I mean, that would be kind of a basic skill in problem finding (erases the 5th arrow). But I think people that we regard as being exemplary in this and doing it very well and therefore demonstrating an aspect of creativity, it helps to explain why problem finding sort of overlaps between wisdom and creativity. They can do the following thing. They can find a problem (Fig. 3c) (draws a 5th circle) that if solved would make a significant impact on these existing problems (draws arrows from the 5th circle). So what I'm suggesting to you is that good problem finding is the ability to generate a problem nexus (writes Problem nexus). So then if you go in and say, "Here's some problems in various domains (indicates the circles) and then they are all centered on this core problem (indicates the circle in the middle). And if we can address that core problem, then we can go back and make a significant impact (indicates the arrows) on this.

I think many of the people—I don't take credit for this. I think the person who should be given credit for this, and I'll talk about that later today is Dreyfus. The idea that many of the central problems of cognition are centered on this ability to realize relevance. I think that's a very powerful kind of problem finding it's the generation of a real problem nexus. And I've tried to show you how it can be very generative of theoretical and empirical research. So I think that's part of what it is to be a good problem finder. It is to generate the problem nexus. I also want to point out something that I'm going to come back to, which is this is going to overlap with an important aspect in some current theories of the nature of understanding that have to do with the effectiveness of how we are relating to knowledge. Now, that sounds very vague and I will come back to that more carefully, but I need you to understand right now is that this problem finding, the ability to generate a problem nexus will also make a significant impact and interact with some of the best accounts, I think, that are emerging about the nature of understanding. And that's going to be important because we want understanding to be part of our theory, our account of wisdom (erases the board).

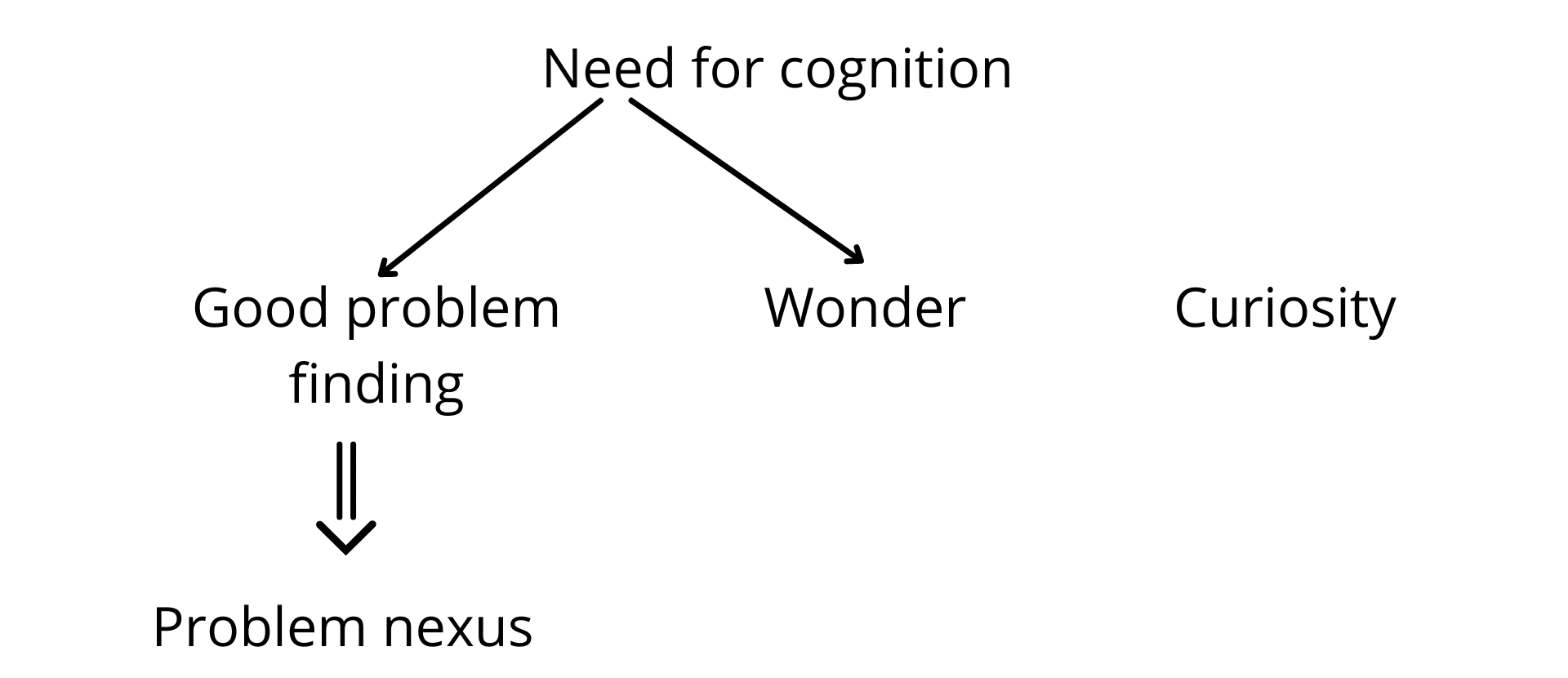

I want to come back to the affective side of this. So I've suggested to you. That one part of good problem finding—sorry, one part of need for cognition (Fig. 4) (writes Need for cognition) is good problem finding (writes Good problem finding below Need for cognition). And then good problem finding is the ability to generate a problem nexus (draws a downward arrow below Good problem finding and writes Problem nexus). The need for cognition. Look at this word here (underlines Need) also points to obviously an affective, a motivational component. And this takes us into the few things I talked about before. Wonder (writes Wonder below Need) and curiosity (writes Curiosity beside Wonder). And I propose to you that, although these terms (indicates Wonder and Curiosity) are slippery, one way in which we can pick up sort of polar opposites is that curiosity is much more in the having mode. It's much more about manipulating and controlling things and wonder is much more in the being mode. It's much more about encountering mystery and calling into question one's worldview, one's identity, etc. So that's why wonder can shade into awe or potentially even into horror.

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Two Different Interpretations To Wonder

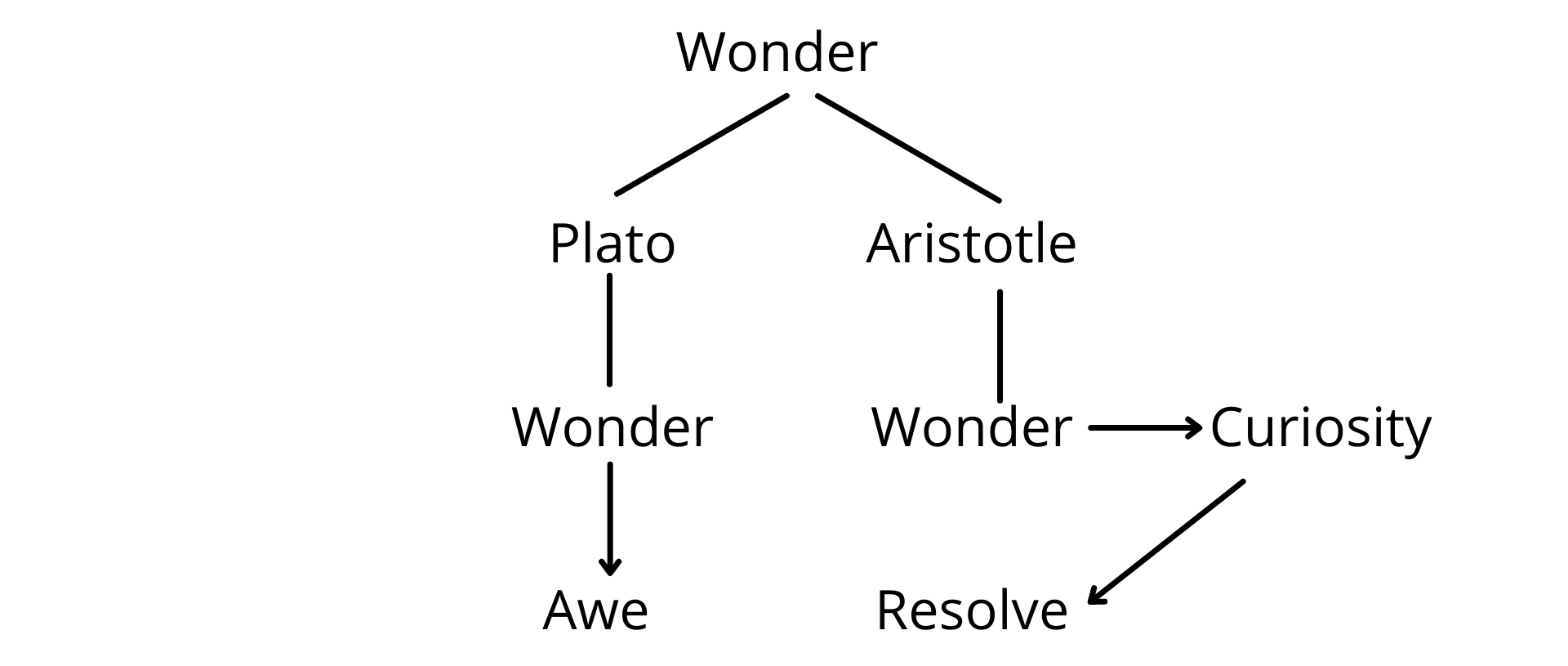

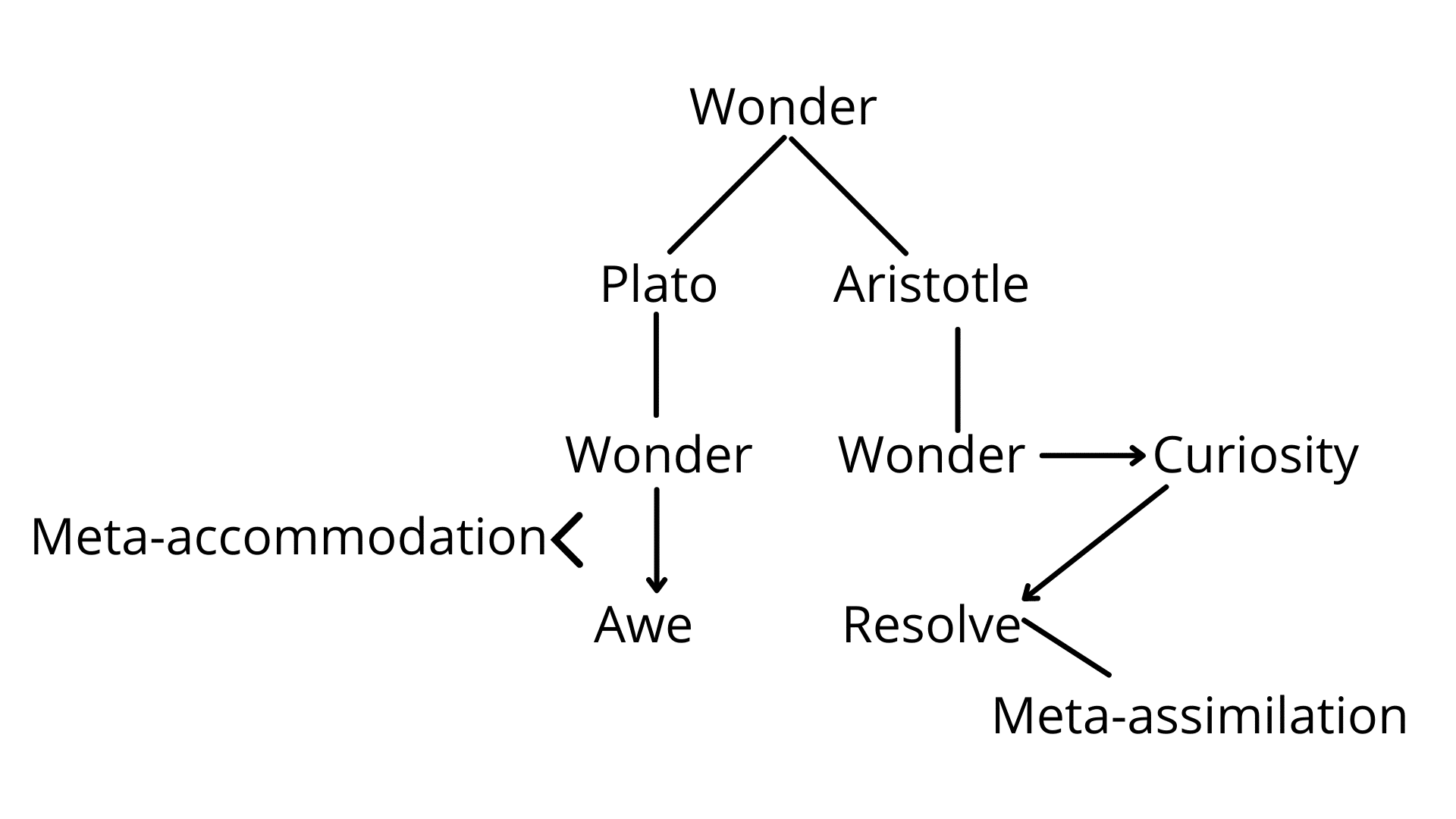

Now I want to pick up on something here, because this again has some very deep connections to wisdom. So I actually have this on a, like a plaque in my apartment. It's a famous quote from Socrates, which is, "Wisdom begins in wonder." Wisdom begins in wonder. And like everything about Socrates, it is simultaneously provocative and enigmatic as to what did Socrates actually mean by that? And there's two different interpretations. And you can see this in the different ways in which wonder (writes Wonder) is treated by Plato (writes Plato below Wonder) and, of course, by Aristotle (writes Aristotle below Wonder). You can see this sort of distinction to some of the current work on wonder.

But for Plato, the point of philosophy is to develop and extend that sense of wonder so that what you're actually trying to do, for Plato, is you're trying to deepen wonder into awe (Fig. 5a) (writes Wonder and Awe below Plato). Because he feels that this awe will have the greatest capacity for transforming us for getting us deeply involved in the anagogic ascent. That makes sense.

Fig. 5a

Fig. 5a

Aristotle also thinks that philosophy begins in wonder, but, I think you could make a good case that—many people have—that Aristotle sees this more in line with curiosity (writes curiosity below Aristotle), trying to figure things out. And then what you're ultimately doing (erases Curiosity), I would say for Aristotle, is this. You're trying to basically shape wonder into curiosity (writes Wonder and an arrow and writes Curiosity) in philosophy and then resolve the curiosity (draws an arrow from Curiosity and writes Resolve) in some answer to some question.

So for Plato wonder sets you on a quest of anagoge, but for Aristotle wonder gets you to formulate questions that you then answer. And that's a fundamental difference between them. And it's interesting because you see Plato is here sort of pushing for meta-accommodation (Fig. 5b) (Writes Meta-accommodation beside Awe) as we've seen before. Well, we talked about this, when we talked about the numinous. And Aristotle is, of course, putting for Meta-assimilation (writes Meta-assimilation beside Resolve). Of course, when I answer questions that may force me to do conceptual accommodation, but overall, this is trying to stabilize and assimilate and sort of home things for you. Now the kind of stuff we saw in Geertz.

Fig. 5b

Fig. 5b

So philosophy is working within that whole structure. And why am I pointing this out? Because of course, again, we're invoking this higher order relevance realization that's at work within this need for cognition within wonder and curiosity (indicates Wonder and Curiosity in Fig. 4).

Alright. So we saw that Stanovich was able to respond to many of the defenders of human rationality in the rationality debate (erases the board). He was able to respond to Cohen by crucially noting that we have to challenge Cohen's assumptions. We do not have a single competence. Well, I also added in that we shouldn't think of it as static or completely individual.

He was able to respond to Cherniak by pointing out that Cherniak was quite right about the centrality of dealing with computational limitations, but that what Cherniak is really giving is not a theory—because Cherniak's theory is a theory of relevance realization—it's not a theory of rationality, but a theory of intelligence. Something that's Stanovich also agrees with, and then to Smedslund, Stanovich acknowledges that we need an independent normativity on construal, and we've already seen that we can answer that. Well, at least I'm proposing that we can answer that by a different area in psychology, which is the work on good problem formulation and insight of problem formulation that avoids the combinatorial explosion ill-definedness and the way in which we can be misdirected by salience to misjudge what is relevant.

Dual Processing Theory

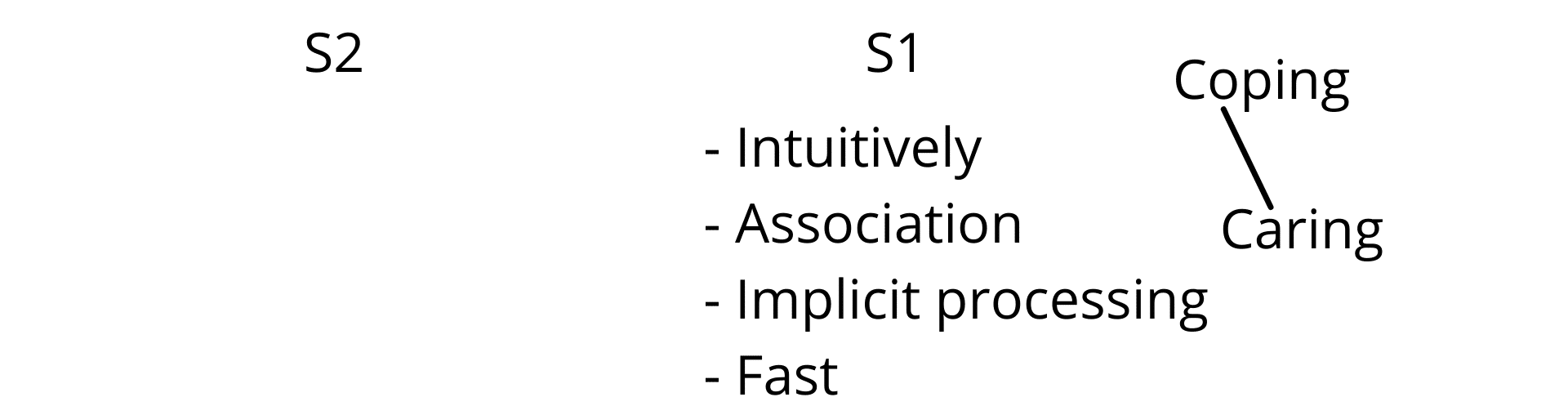

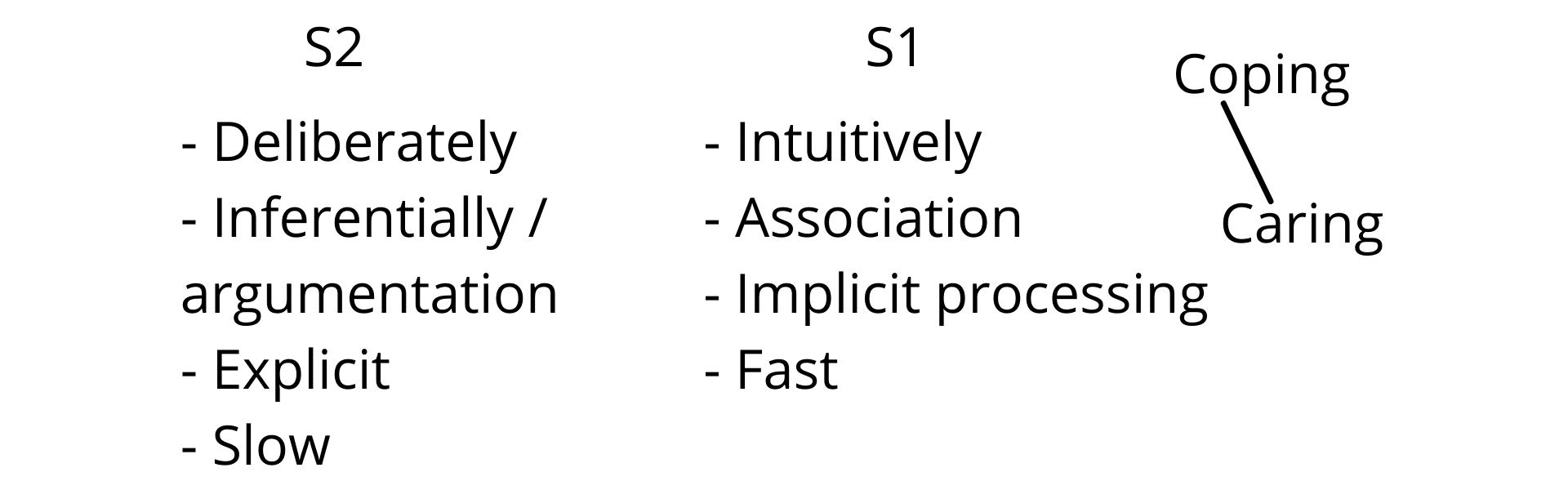

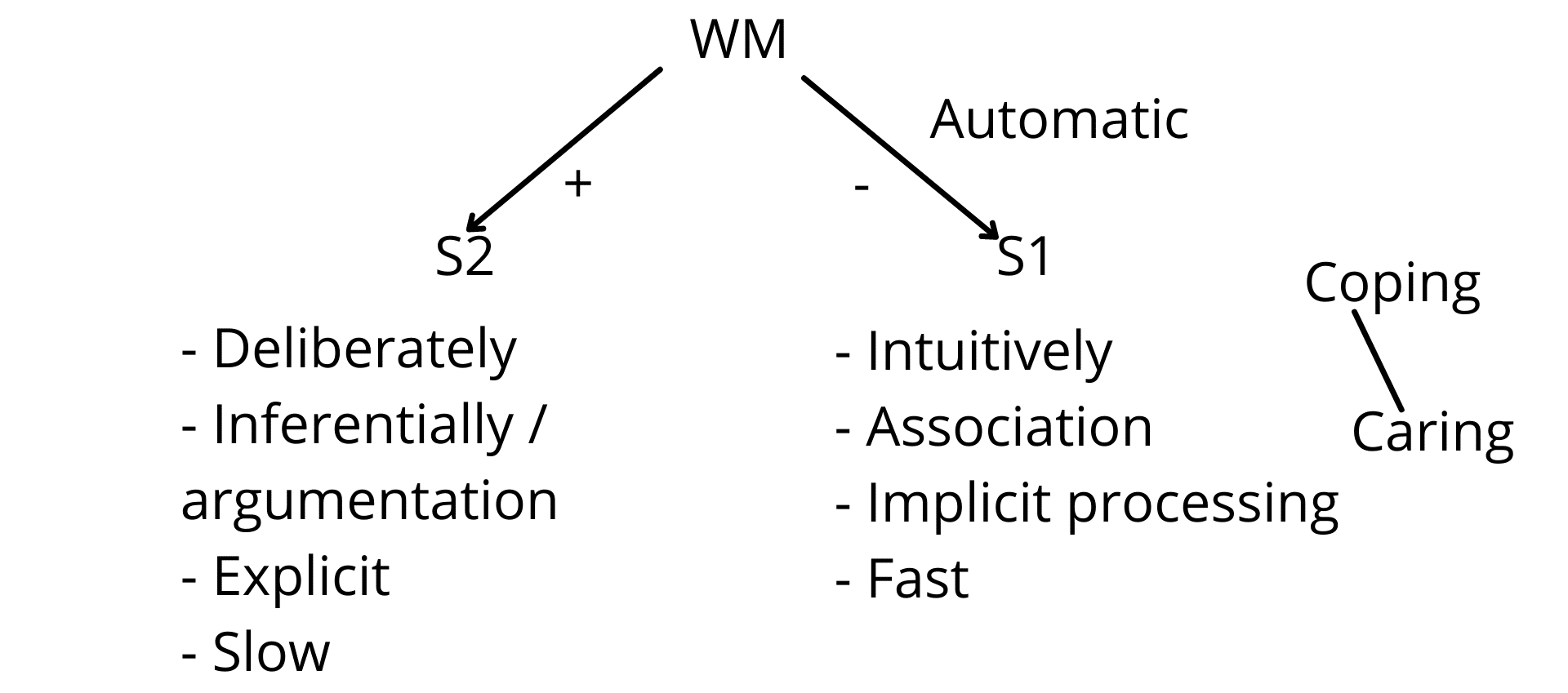

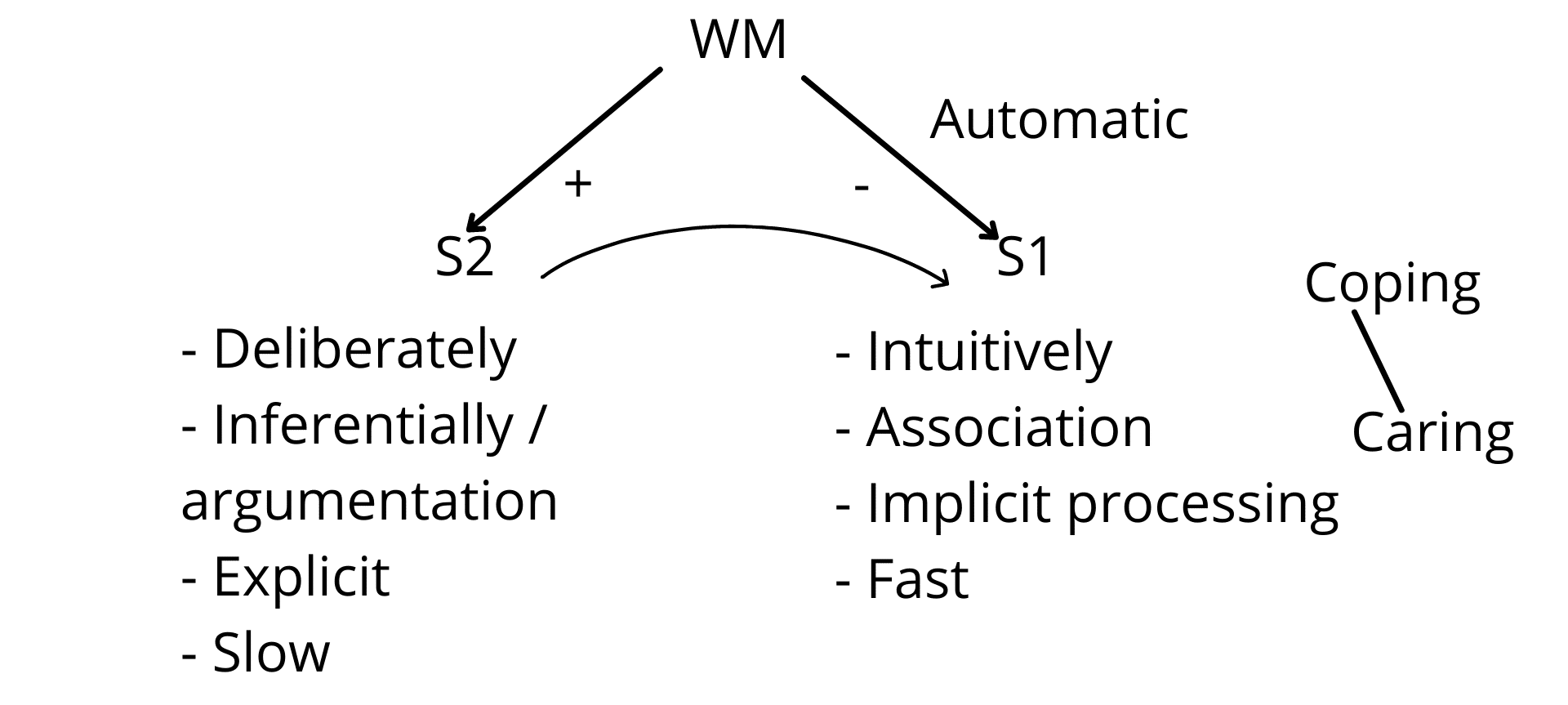

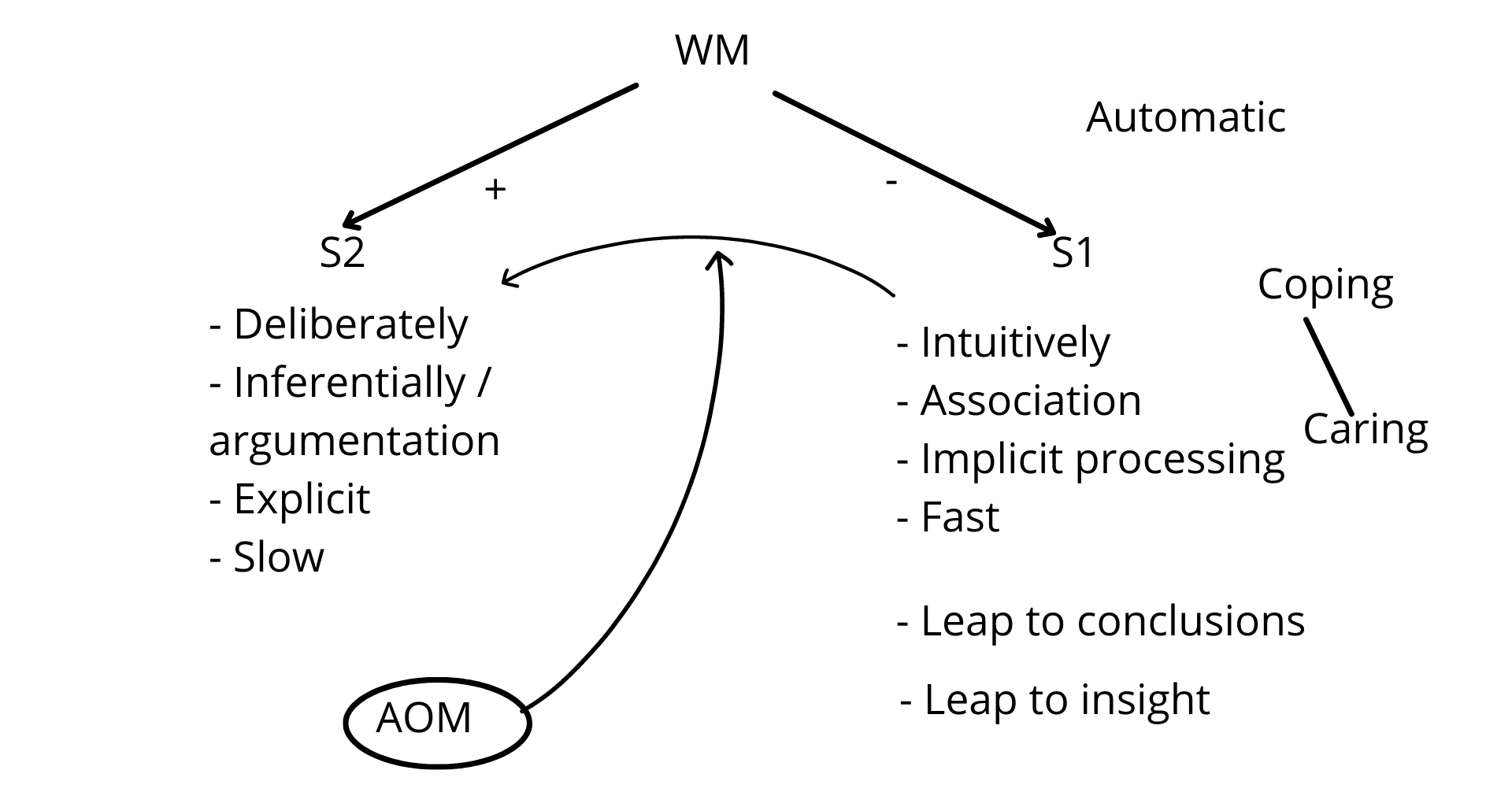

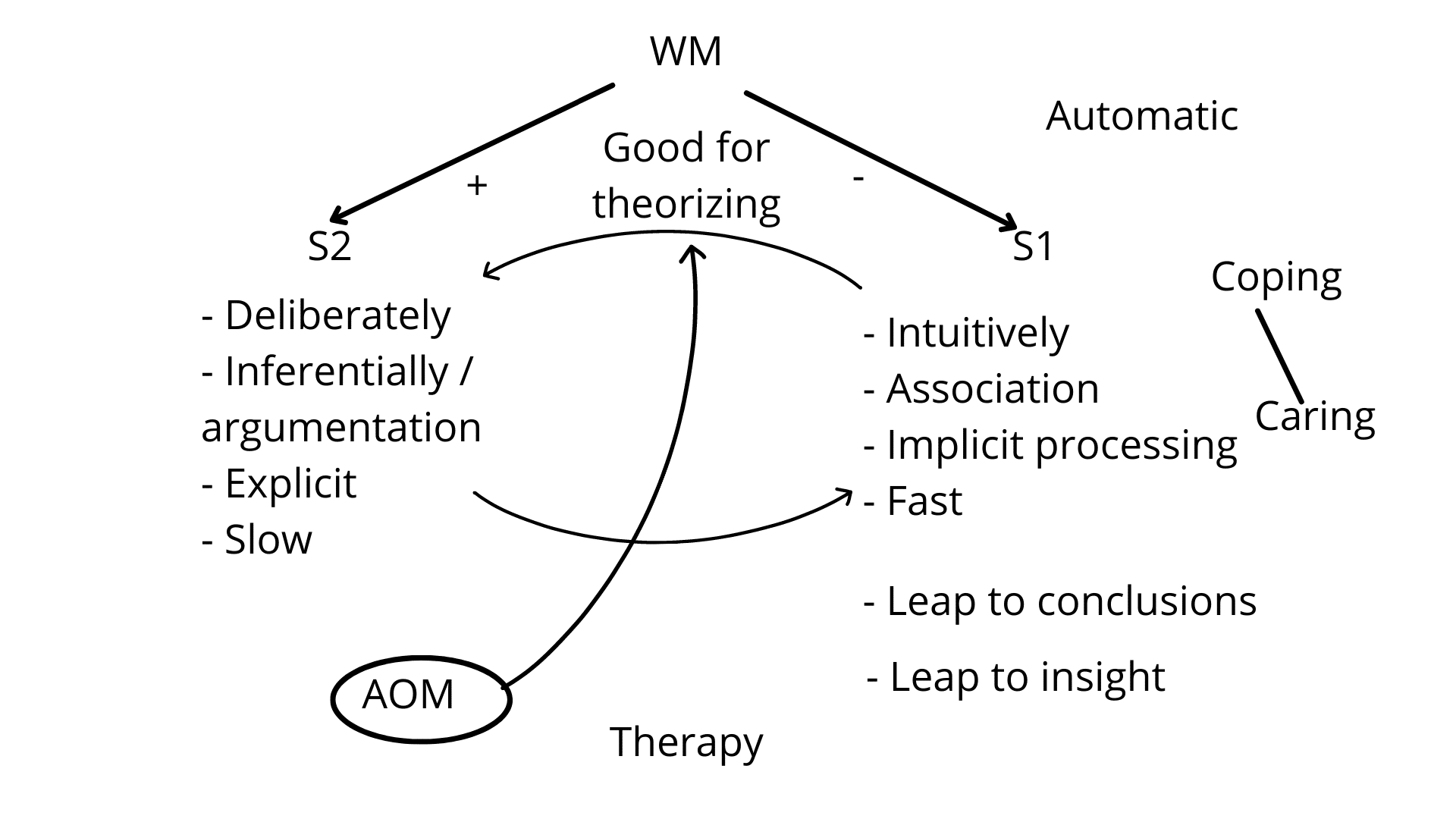

I now want to to return to Stanovich's theory properly. What's his positive account of what rationality is? So the way Stanovich does this —and I don't want, sorry—the way he's doing this overlaps with a lot of other work, and this is a point that he himself made. There's a lot of convergence in psychology on the idea of a dual processing theory that we have multiple competencies. Now, what this dual processing is itself very controversial. Initially, people talked about two systems and then they talked about two styles. And because of critiques, it was hard to maintain those terms. And I'm not even convinced that they are, you know, that there are distinct things. They might lie on a continuum, but the basic idea—so to avoid all that controversy, they're simply called S1 and S2 (Fig. 6a) (writes S2 and S1). And like I say, I'm not claiming that they're discrete systems or even discrete styles, it's quite possible that they are polar positions on a continuum of processing. I'm going to put all of those aside because it's not relevant for what we're talking about here. Right?

Fig. 6a

Fig. 6a

So the main idea here is that these are different ways in which you process information. And this process (S1) works largely intuitively (writes intuitively below S1). It works very much in a highly associational fashion (writes association below S1). It makes use of a lot of implicit processing (writes implicit processing below S1) and it's very fast, right (writes fast below S1)? It's very fast. So this is the kind of processing that you're using all the time in what we've, you know, when we talked about this, when Varella talked about your ability to cope (writes Coping beside S1). This is your coping, right? So when I'm moving around the environment, I'm relying a lot on my intuitive knowledge, my capacity for implicit learning, the way I can quickly associate things together, right? And so I would add to this, of course, as I argued before, that this is also (writes Caring below Coping) sort of how we're primarily caring for things, being involved with them, finding them salient, et cetera. But nevertheless, this (indicates S1) is the part of your cognition that is operating a lot of the time in the background.

In fact, I want to, I'm going to step aside from Stanovich for a moment and propose to you that instead of thinking that these are discrete systems, we can think of different states where you're in, where one style or other is more foregrounded, and the other is more backgrounded. So I'll come back to that.

Let's do the—what's S2?, Well, S2 operates more deliberately (Fig. 6b) (writes Deliberately below S2) in both senses of the word, like deliberation, where I'm engaging in reflection and deliberate in the sense that I am aware of it and intentionally directed in it. So it's deliberately, right? So it tends to not work associationally, it tends to work inferentially, argumentatively (writes Inferentially / Argumentation below S2). Right? Argumentation in the philosophical sense, not in the sense of having an emotional conflict with somebody. The processing, of course, all processing has—and this is an important point—some aspects of it that are implicit. So this is more of a contrast of emphasis, but this processing is much more explicit (writes Explicit below S2) and it tends to be very slow (writes Slow below S2).

Fig. 6b

Fig. 6b

So Kahneman has a book out right now, Thinking fast and thinking slow that is a very good sort of discussion of this dual processing model. Because, as I said, there's a lot of theoretical argumentation and evidence that is converging on this. So this is a very highly plausible thing. And you see it showing up in many, many different domains within psychology.

Alright, so one way of thinking about this, and this is a way in which Stanovich and Evans have tried to get a clearer, more precise way of distinguishing the two is the degree to which they're tapping, making use of working memory. So the idea is S2 really relies on working memory (Fig. 6c) (writes WM and draws an arrow pointing to S2), whereas S1 (draws an arrow from WM to S1) relies much less on it (writes + beside the arrow from WM to S2 and writes - beside the arrow from WM to S1). And so it's much more automatic (writes automatic beside the arrow from WM to S1) in that sense and its operation.

Fig. 6c

Fig. 6c

So let's, let's take an example where you use the two systems, right? So you're grocery shopping and you come up to the cashier and they're ringing you in. And you've got a normal sort of basket full of normal groceries. And the cashier says to you, well, "It'll be $1,000 please." And you go, "What?" Now, where did that "what" come from? Where did that "what" come from? Well, you have associations between sort of these objects, their prices, sort of the amount you've picked up implicit patterns, right? Notice how intuitively associationally, implicit and quickly you do, "What? That's wrong. It can't be a thousand dollars. That makes no sense." So you call the cashier in the question by using your S1 processing. Now what the cashier has to do. She can't just—she or he can't just respond this way (indicates S1) to you. The cashier can't go, "Nah, it's a thousand. I can sense it." What do they have to do? They have to deliberately—no, they have to take out each thing. They have to get out the bill, they have to deliberately, right—Notice that—to concentrate, they have to pay attention step-by-step, make the argument to you explicitly and slowly (indicates Explicit). "No, no look, look, look. Look at—this matches this..." They're using S2 processing.

Now, these, of course, are in a tradeoff relationship because the problem with—and this, of course, is, and Stanovich acknowledges this but part of the problem with this (indicates S2) is how much demand it puts on your working memory (indicates WM), how slow it is. So you cannot rely on it. Yet another argument why you can't Descartes your way through your whole of your existence, right? You can't rely on it (indicates S2) for most of your behavior because you will just head into the ocean of combinatorial explosion. You will get so slowed down and so overwhelmed that you won't be able to live your life. You'll commit cognitive suicide. But, of course, we have this (indicates S2) for a reason. We have this because it is supposed to override to a degree this (indicates S1). So notice that these two systems are in a, basically, an opponent relationship. They are both working towards the same goal of making you adaptive but they tend to work in opposite fashions and Stanovich sees S2 as largely having, and there's deep truth to this, having a corrective function for S1 (Fig. 6d) (draws an arrow from S2 to S1).

Fig. 6d

Active Open-Mindedness

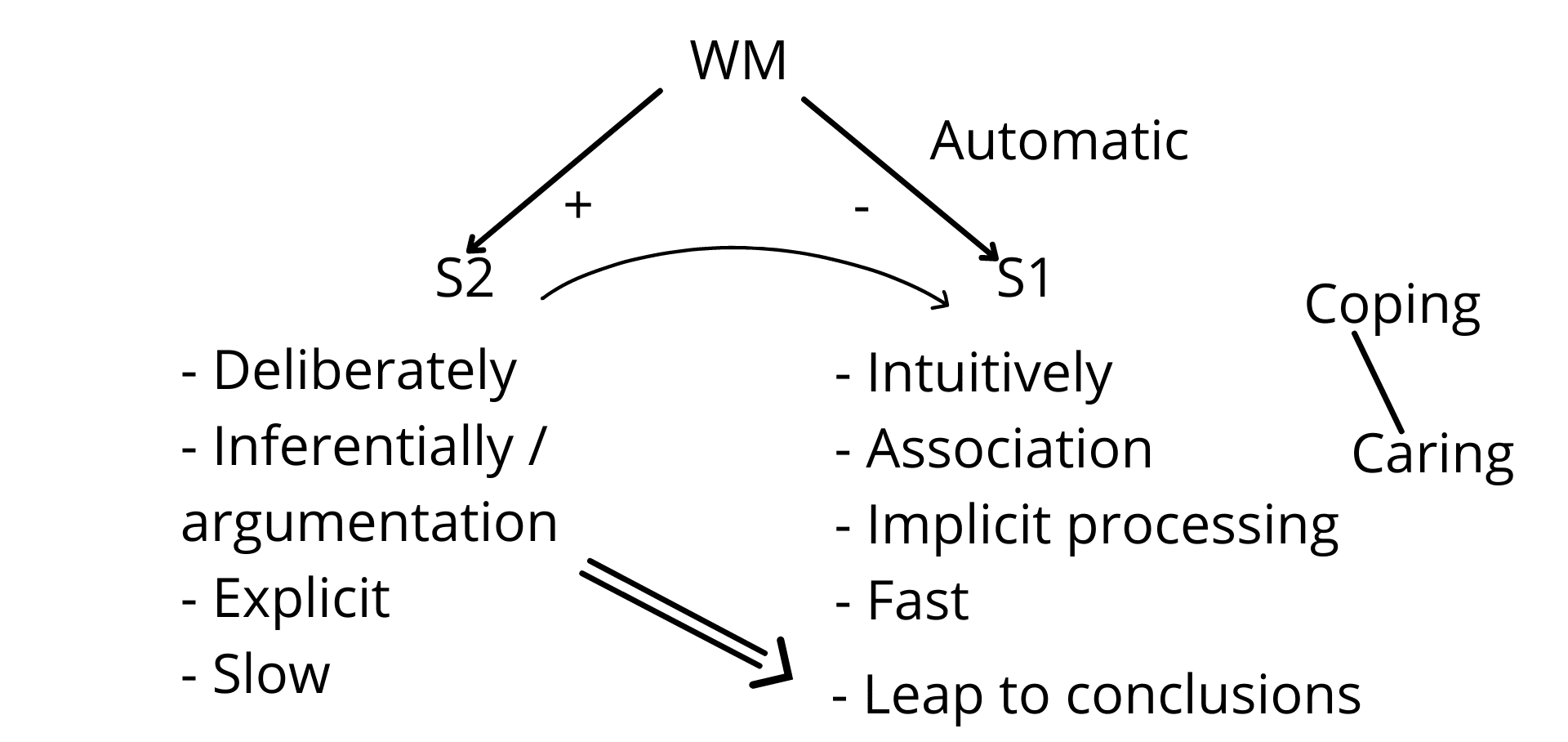

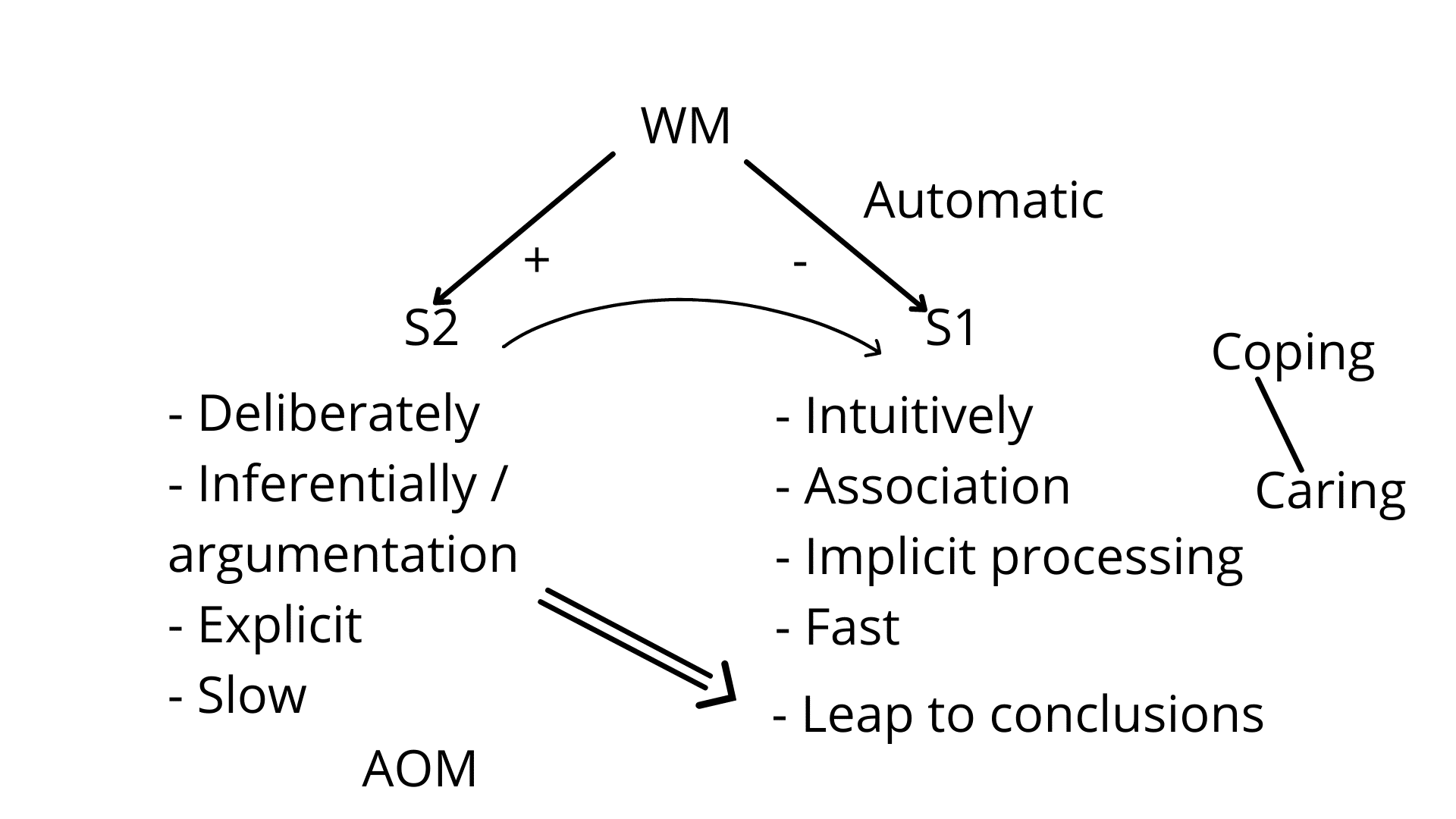

Alright, so now I can first give you his theory of foolishness, which he understands as dysrationalia (writes Dysrationalia), like dyslexia. And then, by implication, his theory of rationality, which, because, it's a comprehensive kind of rationality it deals with a comprehensive kind of foolishness, it's now bordering on an account of what wisdom is. So here's the idea: what is active open-mindedness doing? Well, what's happening is this (indicates S1) is the place where, you know, all the heuristics and biases are. This is where they're operating. And what happens here is they make you leap to conclusions (Fig. 6e) (writes Leap to conclusions).

Fig. 6e

Fig. 6e

Remember when I did the problem with you, you know where you've got the pond and on day one, there's so many lily pads and it doubles every day. And on day 20, it's done. On what day was the pond half-covered? And your S1 shouts at you, "10 days. 10 days in 'cause it's half and half. And that's how it works." And that's wrong because on day 19 half, the pond was covered, right? And what you have to do is S2 has to basically override (draws an arrow from S2 to Leap to conclusions) how you're leaping to conclusions. How you leap to the conclusion that the people at the airport are in danger because of the representative heuristic or the availability heuristic. So S1 is constantly giving, but I need this—that's what makes me fast. If I'm not leaping, I'm not fast. I'm not coping. Leaping and coping are deeply interdependent. Okay? But the thing is sometimes, and again, it's unclear what the degree is, that's one of the ways in which I think Baron is a little bit more clear than Stanovich, but sometimes we need to override this leaping to conclusion.

So he sees that what active open-mindedness (Fig. 6f) (writes AOM) is basically doing is teaching you to protect this (indicates S2) processing from being overwritten by the way S1 makes you leap to conclusions. You are foolish. You have dysrationalia if you are highly intelligent and yet you do not—you have not trained S2 (indicates S2 and AOM) to be properly protected from the interference (indicates Leap to conclusions) from S1. Do you see what's going on here? This is how he's ultimately responding to Cohen. You have these two competencies (indicates S1 and S2) you need both of them. They are constitutive of your cognitive agency. So they're both (indicates S1 and S2) constitutive competences, but this one (indicates S1) can interfere with this one (indicates S2), and that can cause you to behave irrationally. What active open-mindedness does is to protect this kind of processing from that interference.

Fig. 6f

Fig. 6f

So that's Stanovich's central model. Now, I think that's definitely a good account of active open-mindedness (encircles AOM). My central criticism of this is I think it's an insufficient account of rationality (erases the arrow between S2 and Leap to conclusions). It's insufficient. I grant a lot of work has been done here. Rationality is not being equated to intelligence is not being equated to logicality. It's centered on overcoming self-deception. There's an account of self-deception. It's so platonic, eh? It's so platonic. Here's the monster (indicates S1) and it's interfering with the man, right? So platonic. And so we get that interference effect. That's, what's causing us to be foolish. That makes us self-deceptive. If we cultivate active open-mindedness, then we can reduce the interference. And that makes us more comprehensively rational. I think that's all, well, it's all elegant. It's beautiful. And the fact that this kind of work keeps getting replicated and massively convergent it's so highly plausible and profound. That's all, I think, that's all worthy of being noted.

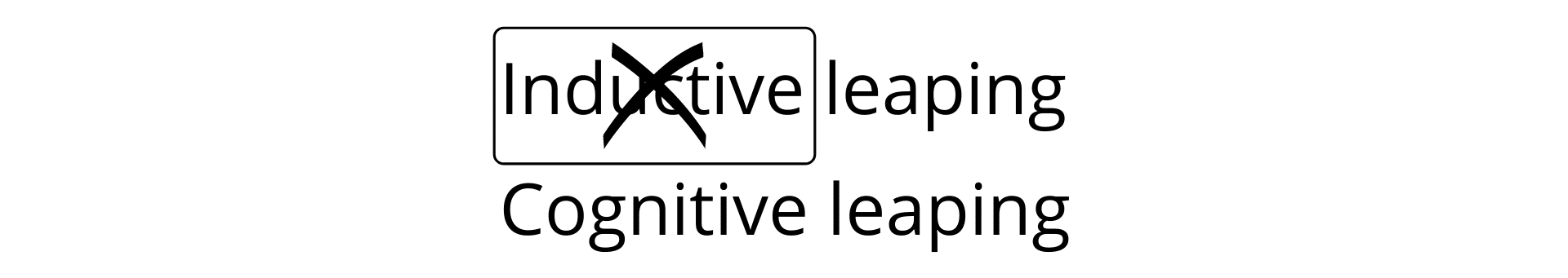

Cognitive Leaping

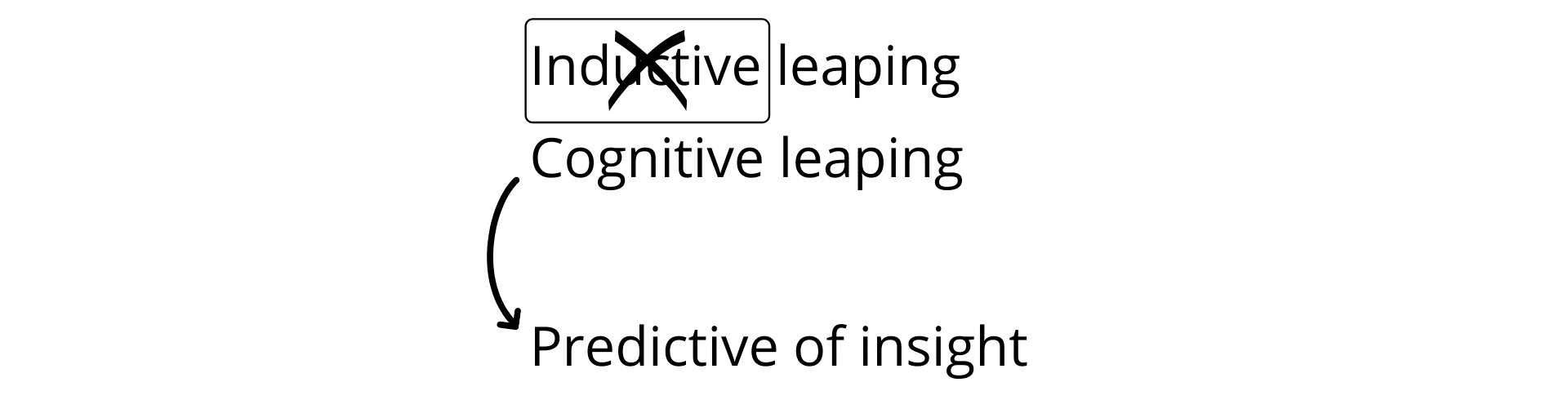

However, let's look to this (underlines Leap to conclusions). Because is leaping always a bad thing? Well, I already implied you need to leap to cope, but let's take a look at the work of Baker-Sennett and Ceci from 1996. Okay. So they investigated a thing they called inductive leaping (Fig. 7a) (writes Inductive leaping). I think calling it inductive leaping is a mistake because I understand induction (encircles inductive) as an inferential procedure and what they're explicitly doing is not inferential in nature. So I'm going to suggest that we don't use that term (crosses out inductive). I'm instead going to use the more neutral term of cognitive leaping (writes Cognitive leaping below Inductive leaping).

Fig. 7a

Fig. 7a

What's cognitive leaping? Well, cognitive leaping—how did they test it? They tested it in the following ways. I give you various patterns that are unfolding across time. And that at various times, I stop and ask you, you can tell me what it's going to be. One version of it is there's, like—we talked about this before—a bunch of dots and what's it going to be? And more dots get filled in. Eventually you're able to leap and say, "Oh, it's going to turn out to be a sofa. I notice how you're doing —you're going from features to Gestalt. You're doing that leap. And you're going from looking at the dots to looking through them. You're doing an opacity transparency shift, all that stuff we talked about, right? Mindfulness is involved.

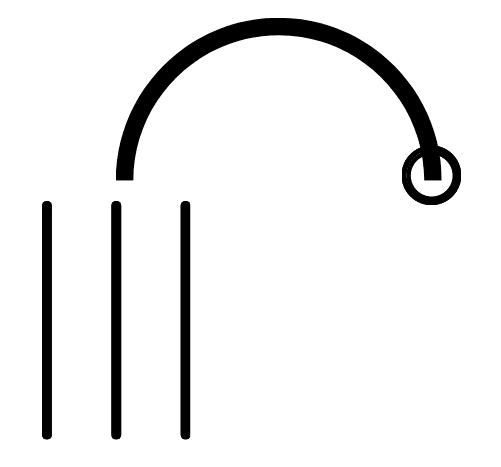

Now, why does that matter? Well, what they found was something very important. This (indicates Cognitive leaping) allowed them to operationalize kind of the, at least an aspect of the inevitability of insight, because often you don't know what's going on in an insight there's this leap. And what they—how they operationalized it was this. You're a good leaper. You're a good leaper if you can use fewer cues (Fig. 8) (draws three lines) and accurately say (draws an arc that intersects with a circle) what the final pattern is going to be. So if you use fewer cues and you're making lots of mistakes, you're not very good; if you're largely accurate, but you have to get a whole bunch of cues that you're not a very good leaper, but if you use few cues and get to the full Gestalt reliably, then you're a very good cognitive leaper. Okay, you're doing this. You have this skill, this facility with pattern detection, pattern completion.

Fig. 8

Why is that so important? Well, because that (draws an arrow from Cognitive leaping), and that's what the experiments show. This is directly predictive of insight (Fig. 7b) (writes Predictive of insight below Cognitive leaping). The better you are at leaping, the better you are at insight.

Fig. 7b

Fig. 7b

So do you see the tension here? If I try to shut off too much leaping to conclusions (indicates Leap to conclusions), I'm also shutting off the machinery (indicates Cognitive leaping) that makes me more insightful. It's—we have, look, we have to give up simplistic notions, naive, simplistic notions of rationality. Yeah, I'm not accusing Stanovich of this, not at all. But what I'm saying is we have to—being rational is a very complex process in which there are trade off relationships and a very complicated kind of optimization needs to be trained.

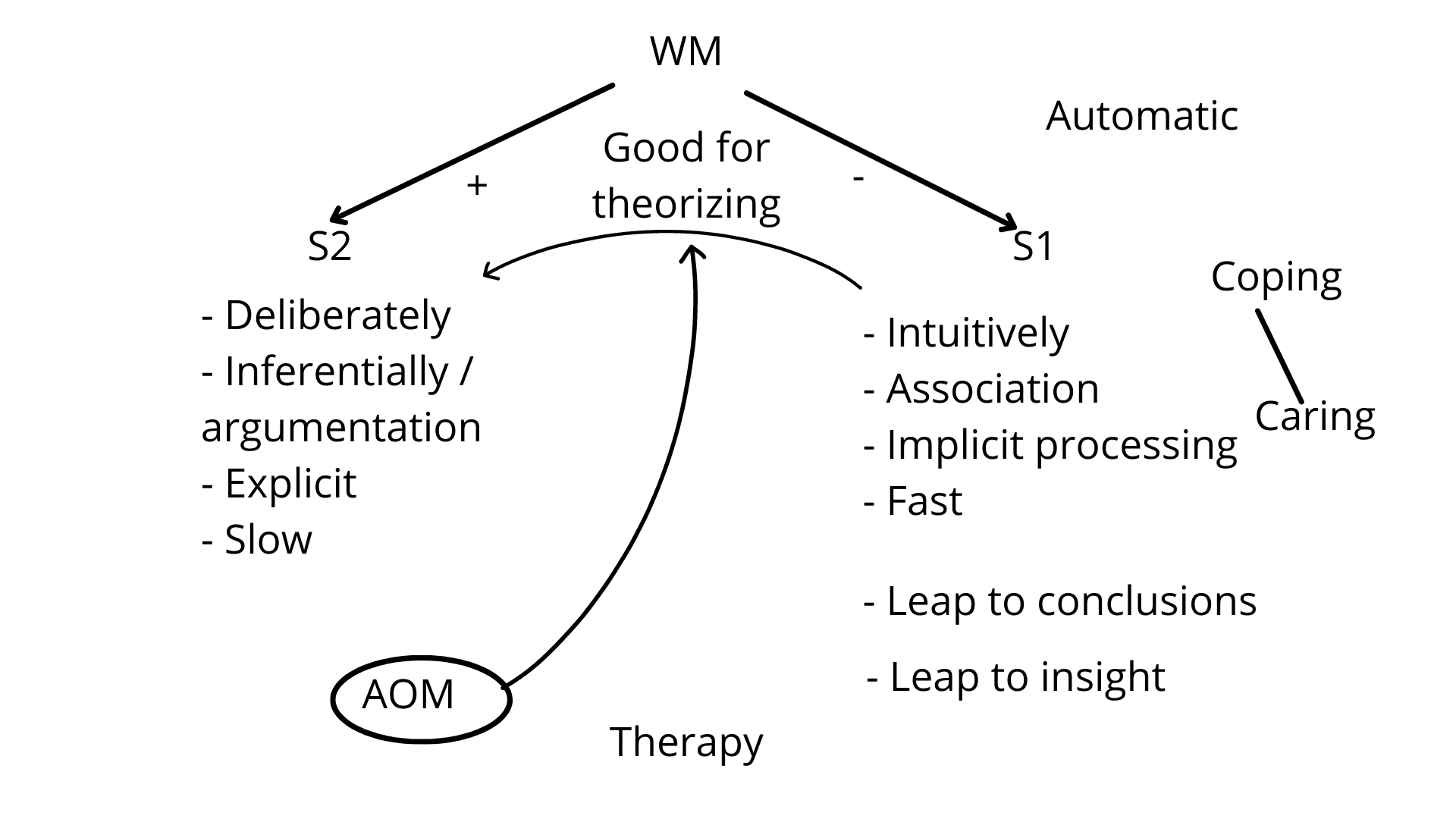

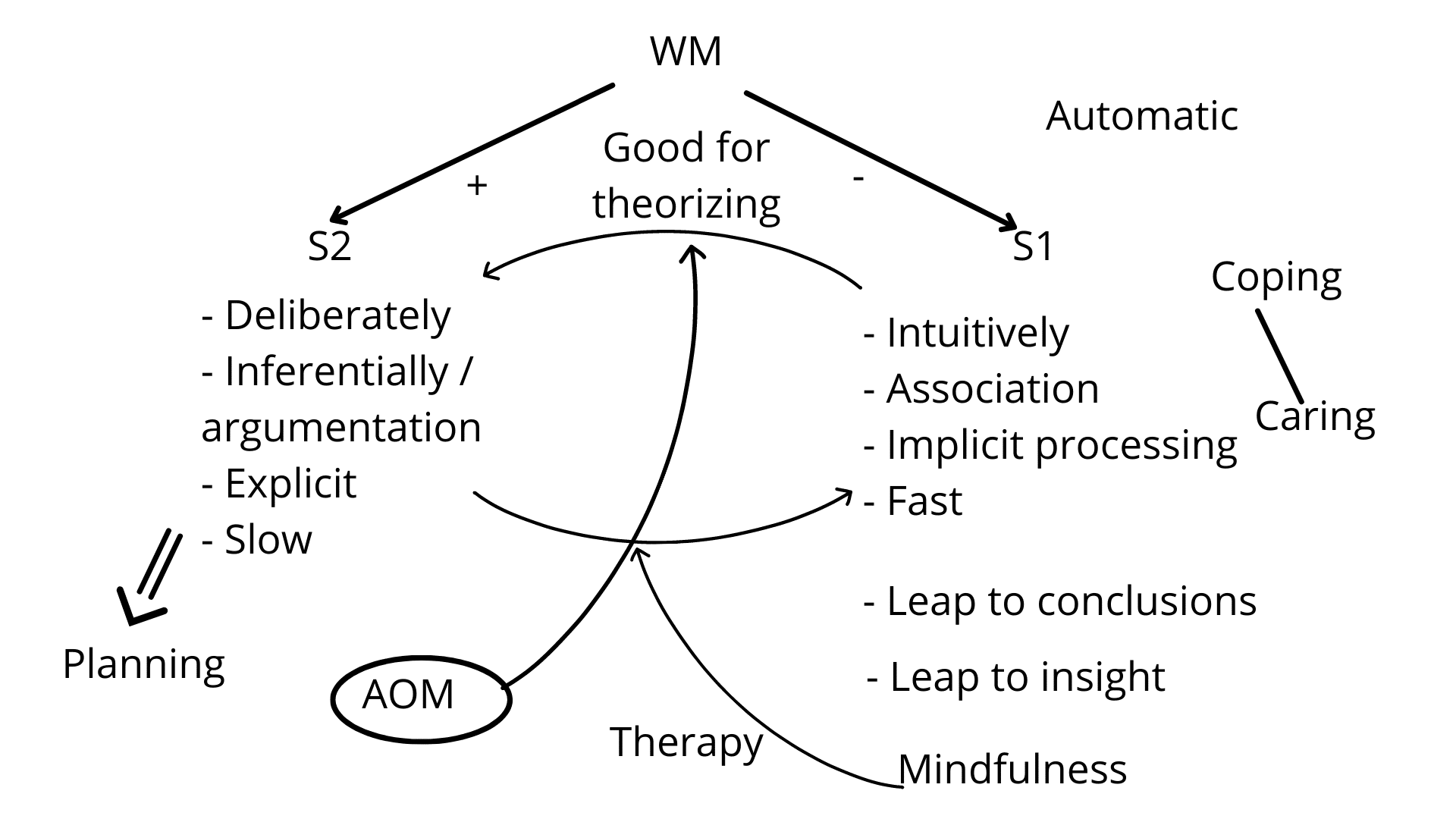

So we want active open-mindedness to pro— (erases the arrow between S2 and S1) Let's make this the error of interference. So sometimes I leap to conclusions (Fig. 9a) (draws an arrow from S1 to S2) and that causes a lot of mistake in inference (indicates S2), the kind of stuff Stanovich— And what I need is active open-mindedness to moderate that (draws an arrow from AOM to the arrow between S1 and S2) and ameliorate it in a significant degree, right? But I want to leap to insight (writes Leap to insight under S1). And I need that for good construal and good construal is central to being a problem solver. Central to being rational.

Fig. 9a

Fig. 9a

Two Different Contexts: Theorizing And Therapy

So what do I need? Well, it's interesting because if you turn to a domain outside of the academic domain and we have to, because rationality is existential, we have to pay attention to the context, even in which we're theorizing about rationality. And if we're in a largely academic context, we're going to think of rationality as primarily about theorizing. And so this (indicates S2 and S1) is a great danger to theorizing. And so I would argue, if the rationality, if the project you're engaging in rationality is the project of theorizing. And I mean, that broadly in the sense of generating scientific, you know, or historical theory, then active open-mindedness is crucial. But there are domains where it goes the other way there's domains in which what you do not—what you need is you need to be able (indicates Leap to insight) to come up with a transformative insight where you need a radical reconstrual of the problem or the issue where that's crucial because you're somehow locked in. Where is the domain in where that's crucial? Well, we've talked about it.

So this is good for theorizing (Fig. 9b) (adds Good for theorizing above the arrow between S1 and S2). But Jacob's in his book, and you can see some related work by Teasdale, points out there's an opposite context. There's the context, not a theory, but there's the context of therapy (writes Therapy). I think it's broader than this (indicates Therapy), but I'm using this because it's a good contrast, there's an alliterative relation (indicates Theorizing and Therapy) to help for mnemonic purposes.

Fig. 9b

Fig. 9b

So in therapy very often what's needed is and we've talked about this, remember? You're existentially trapped and you need this fundamental kind of transformative insight and you cannot infer your way through it. We've already tackled that argument in detail. You cannot infer your way through it. And the problem in therapy is people try to think their way through it. That's Jacob's main point. And I say it related in a book called The Ancestral Mind. And the same point is being made I think by Teasdale, when he talks about metacognitive insight being central to therapy. Often, what you need is to try and shut this down (indicates S2), try to trigger this. (indicates S1). I mean, think of Freud and free association. You have to try and shut this down (indicates S2), prevent it from interfering (Fig. 9c) (draws an arrow from S2 to S1 and crosses it out and erases the cross). Bring this (indicates S1) into the foreground. Keep this (indicates S2) in the background.

Fig. 9c

Fig. 9c

So when we're theorizing, we need this (indicates S2) in the foreground and we need it protected. We need it to seriously background and constrain this (indicates S1). Active open-mindedness in doing this. But in the therapeutic situation, this (indicates S1) needs to be much more foregrounded this (indicates S2) needs to be backgrounded and it (indicates S2) needs where it needs to be constrained so it doesn't unduly interfere with this.

Mindfulness

Now, what we can ask ourselves is, well, what's a cognitive style that makes this (indicates S1) much more focal, tries to constrain this (indicates S2) and really improves insight (underlines Leap to insight)? Well, we know what that is. And Teasdale in fact, argues for it explicitly as to what triggers meta-cognitive insight. That's mindfulness (Fig. 9d) (writes Mindfulness below S1). So you think about how much in a mindfulness practice, I've tried to argue that there we need an ecology of psychotechnologies to cultivate the cognitive style of mindfulness. Think of one, think of meditation. Think of how much in meditation you are trying to really constrain this (indicates S2), shut this down, reduce all that inner speech, all that inferential processing that deliberate direction. And you're trying to open this (indicates S1) up in a very powerful way. So notice that I now have (encircles Mindfulness) a cognitive style that is (indicates AOM and Mindfulness), in a very important sense, opponent, not adversarial, but opponent to active open-mindedness.

Fig. 9d

Fig. 9d

Notice that they are both sharing the training of attention and what you're paying attention to and how you're paying attention. So, this is great for planning (writes Planning below S2). And this is, I said, this (indicates S1) is great for coping. And especially when the planning is epistemic, when we're trying to theorize, when we're planning for truth. This (indicates S1) is very good for coping, especially when we're doing a kind of coping that's therapeutic in a broad sense in which we are needing to transform and undergo important qualitative development.

So I think what's missing from Stanovich is a broader account of our competences and how they can be—how they are played off against each other, how there's a tradeoff relationship with them. And part of what, I would argue, and I'm going to come back to this more directly later, what goes into wisdom is a cultivation of both active open-mindedness for inference (indicates Good for theories) and mindfulness for insight (indicates S1), and then what we're going to need is—well, what coordinates them together (indicates S1 and S2)? How are they coordinated together? How do I optimize the opponent—not adversarial—how do I optimize the opponent processing between them? I want to come back to that and explore that in detail with you, because I can't push this any farther because as we push this farther, we're getting farther and farther away from Stanovich's theory and moving in towards a theory that I myself am going to propose to you. The work I've done with Leo Ferraro and then, sort of, critically reflect on that. So I need you to remember this for when we come back to more explicitly talk about a theory of wisdom and to be fair to Stanovich, he's ultimately not offering a theory of wisdom. And I think when he talks about rationality, He really means theoretical rationality, as opposed to what we might call practical or therapeutic rationality (indicates Therapy).

Okay. I want to stop here though and note it and continue on with our investigation now of explicit theories of wisdom, but I want to sort of pull one thing out of our discussion from Stanovich before we leave Stanovich's good company (erases the board). I want to use somebody else's work to extend that a bit and to just add more teeth to this claim that rationality is ultimately an existential issue.

Intelligence, Rationality, Wisdom

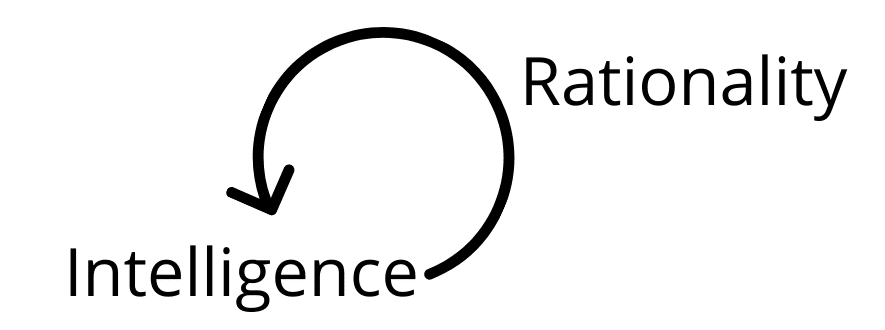

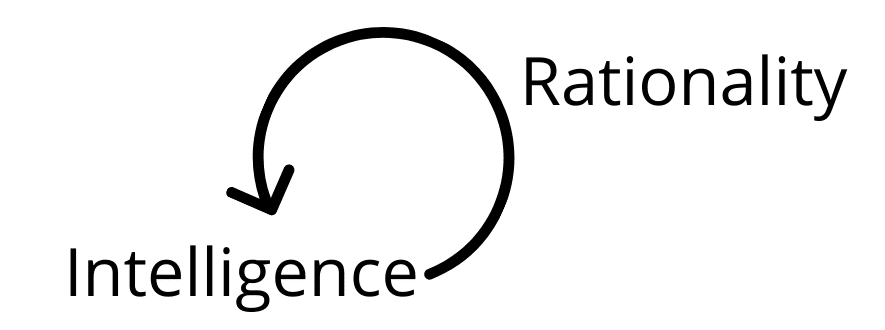

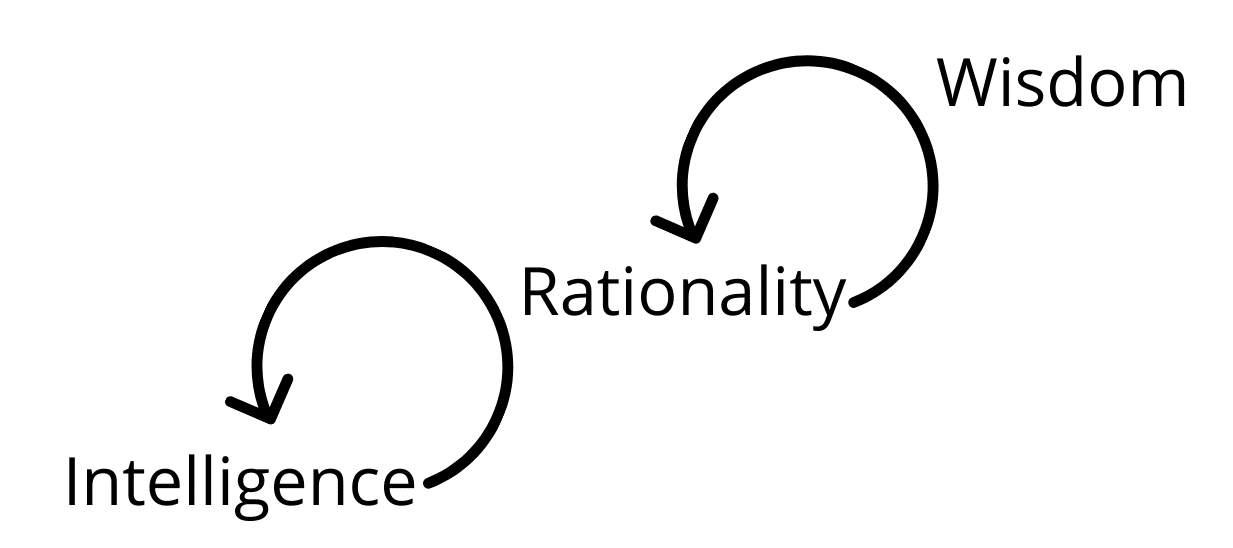

A way of understanding what Stanovich says is the following (Fig. 10a) (writes Intelligence). Right? When I use intelligence to learn the psychotech and the cognitive syle, I can use intelligence to actually improve (draws a circular arrow from Intelligence to intelligence) how I'm using my intelligence. I can use my intelligence to improve how the competencies are optimizing and I can therefore overall enhance my capacity for relevance realization. We can think of that as rationality (writes Rationality beside the circular arrow).

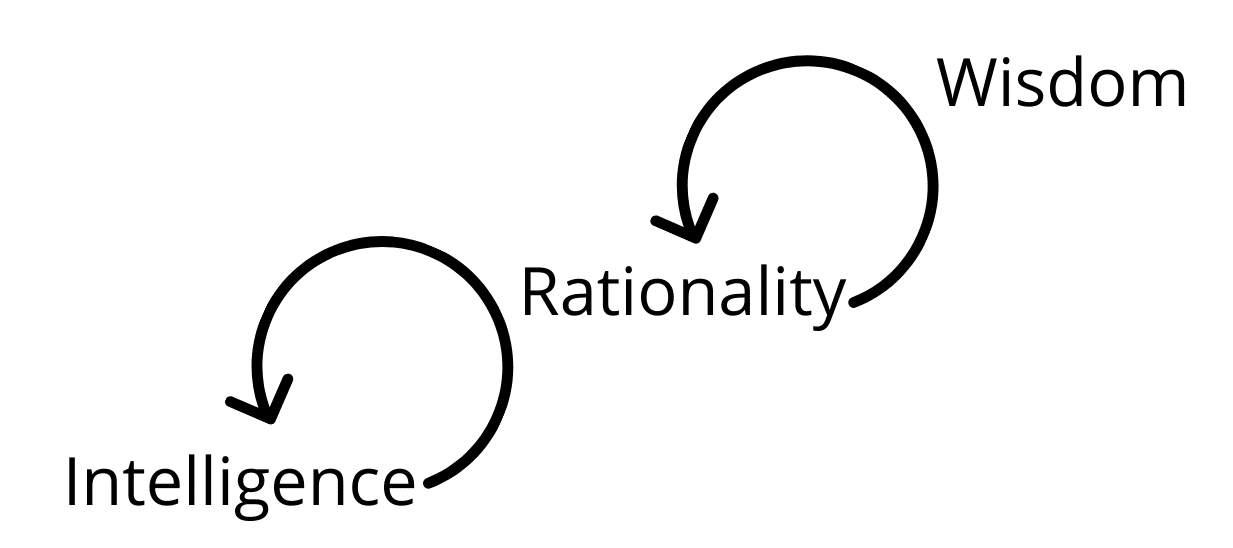

Fig.10a

But something else is emerging right out of this, which, I'm only suggesting now, but we may perhaps be able to use our rationality to improve our rationality (Fig. 10b) (draws a circular arrow from Rationality to Rationality), to make it more optimal overall. And I would suggest to you, that's going to be crucial to wisdom (writes Wisdom beside the second circular arrow). That's going to be an essential feature, I would argue—not everybody agrees with me on this I'm trying to be really clear about this—but I would argue that that (indicates Fig. 10b) is a place in which we can find the locus for understanding the nature of wisdom, how it relates to rationality and how it relates to intelligence. What the nature of this (indicates the circular arrow pointing to Rationality) is we're going to have to come back to one more time (taps Rationality). Please remember when you see this word (Rationality) that I am not equating it to logicality or intelligence, I've given you long arguments, but I've tried to expand this notion, right? It's as much more about the reliable and systematic ability to overcome self-deception and to afford the enhancement of development and meaning in life. That's what I mean by that. Okay. So (taps Wisdom). Let's keep this in mind (indicates Fig. 10b).

Fig. 10b

Let's take some time now (erases the board) to take a look at some more explicit theories of wisdom. I can't look at them all. This is a growth industry. I'm going to a conference tomorrow that has a lot of the people that are working in this. And it's going to be a discussion to try and see if we can come to some consensus about this precisely because it is such an important topic. A lot of good work has been done on it, but again, because there is such a multitude of viewpoints, getting a clear consensus on this is going to be a theoretical challenge.

The Existential Aspect Of Rationality

Okay. I want to, as I said, do one more thing before I do that before I move to the explicit theories. And I want to show you, I want to show you a bit about this (Fig. 11) (writes Intelligence with a circular arrow pointing to itself). And the point about this is to bring out something that Stanovich is not addressing, which is the existential aspect of rationality, the degree to which we identify with our higher cognitive processes.

Fig. 11

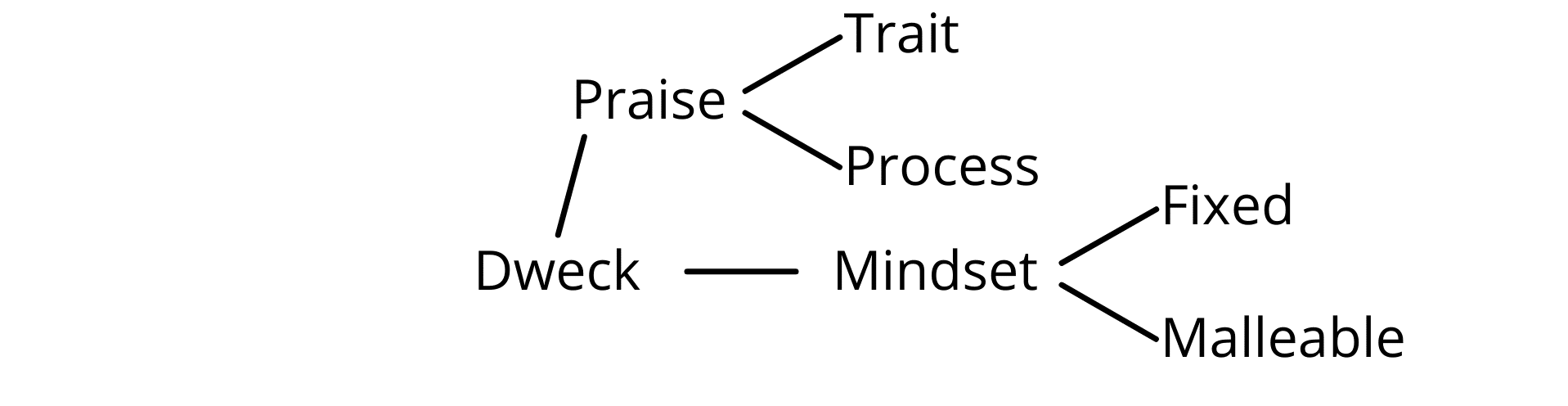

Okay (erases the board). So this is the work of Dweck (writes Dweck). Carol Dweck, and its work on mindset (writes Mindset beside Dweck). She has a book entitled that, and this is, of course, is again, an ongoing thing it's been taking up in a lot of different research.

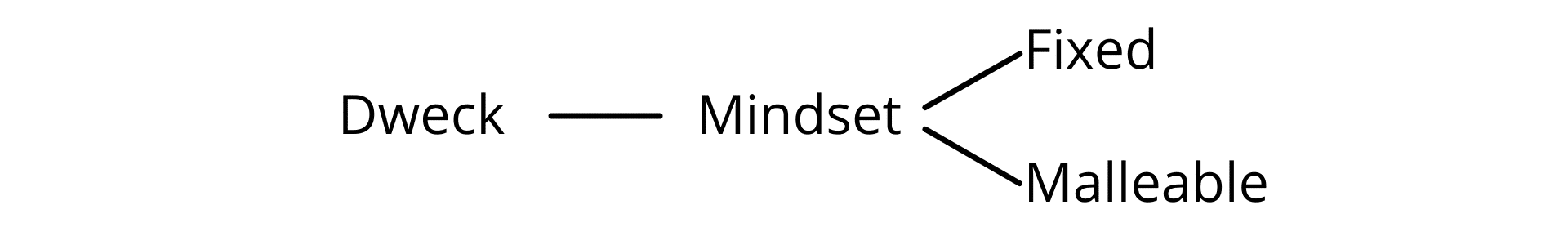

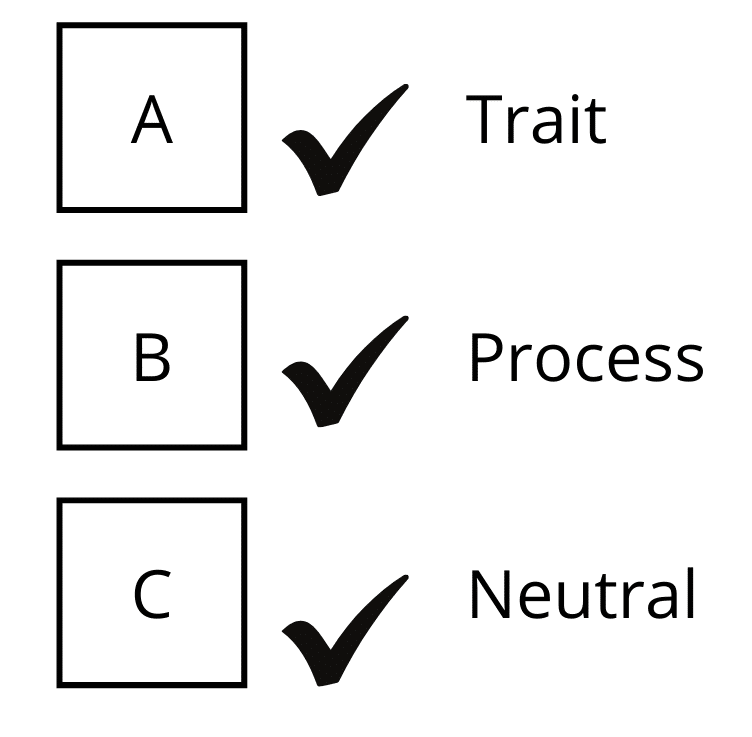

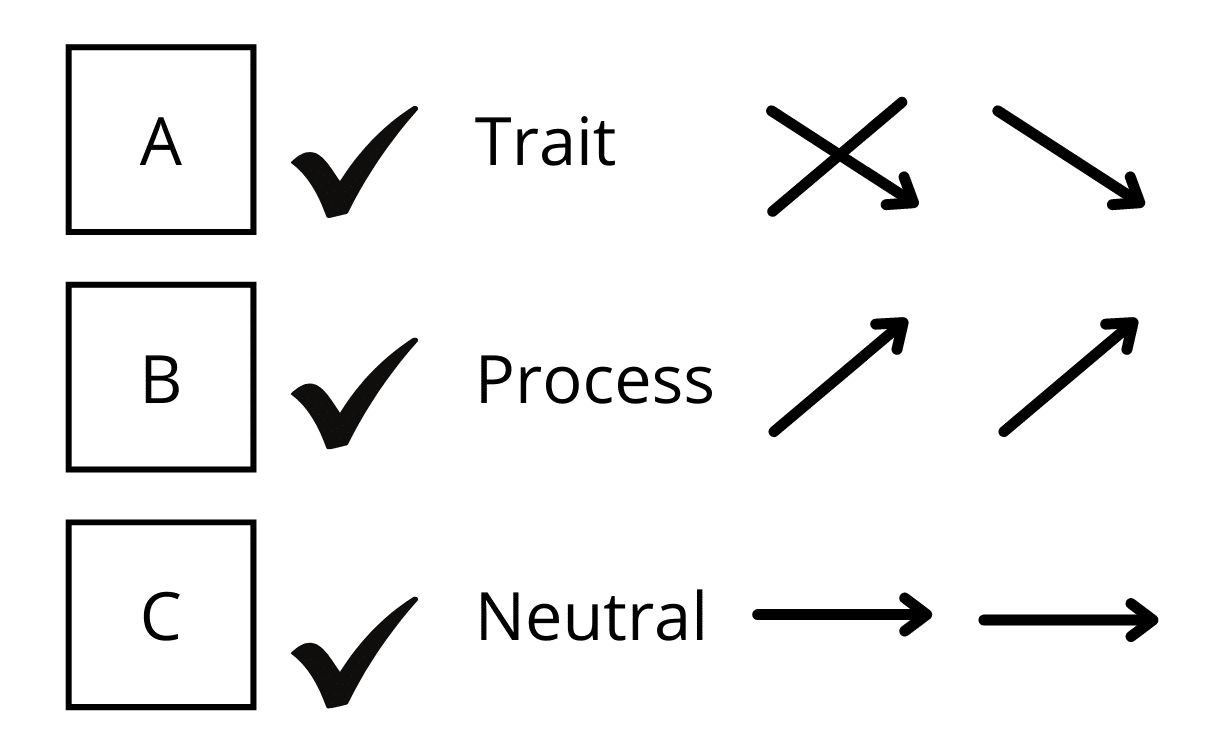

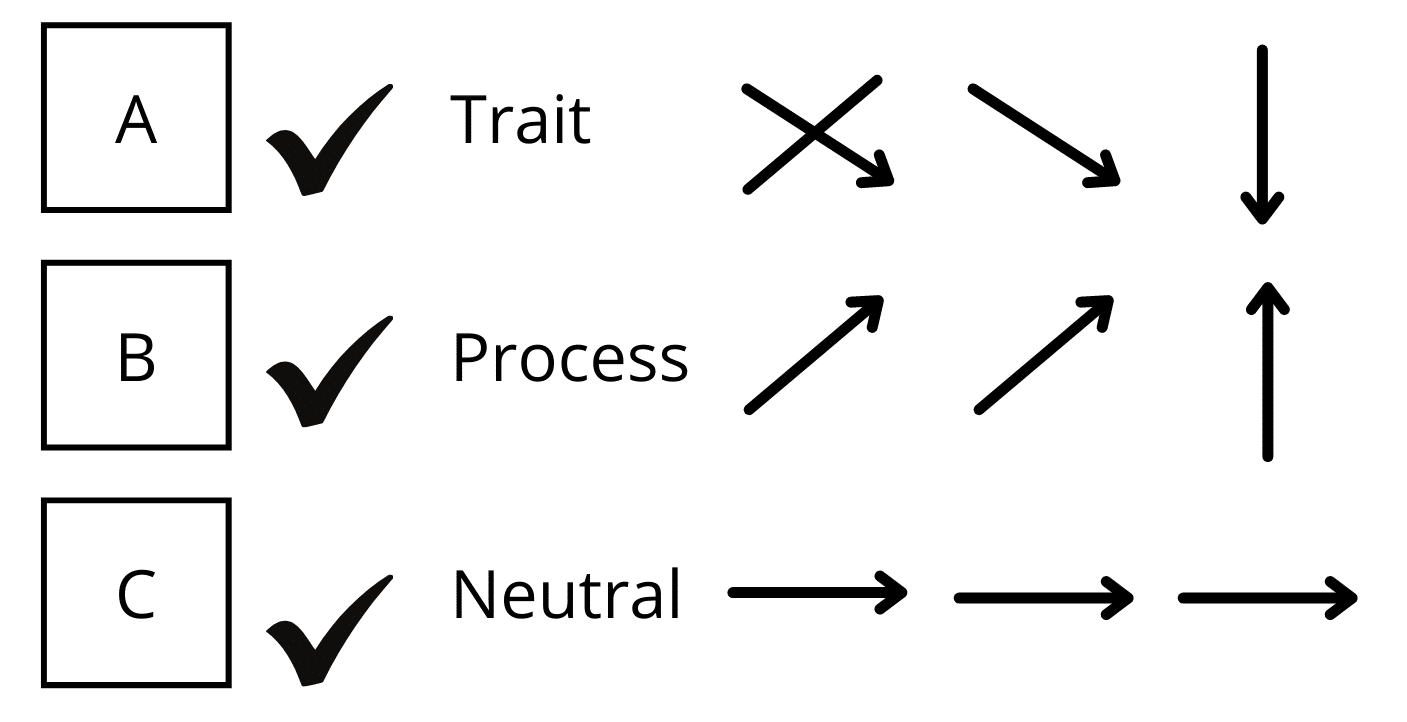

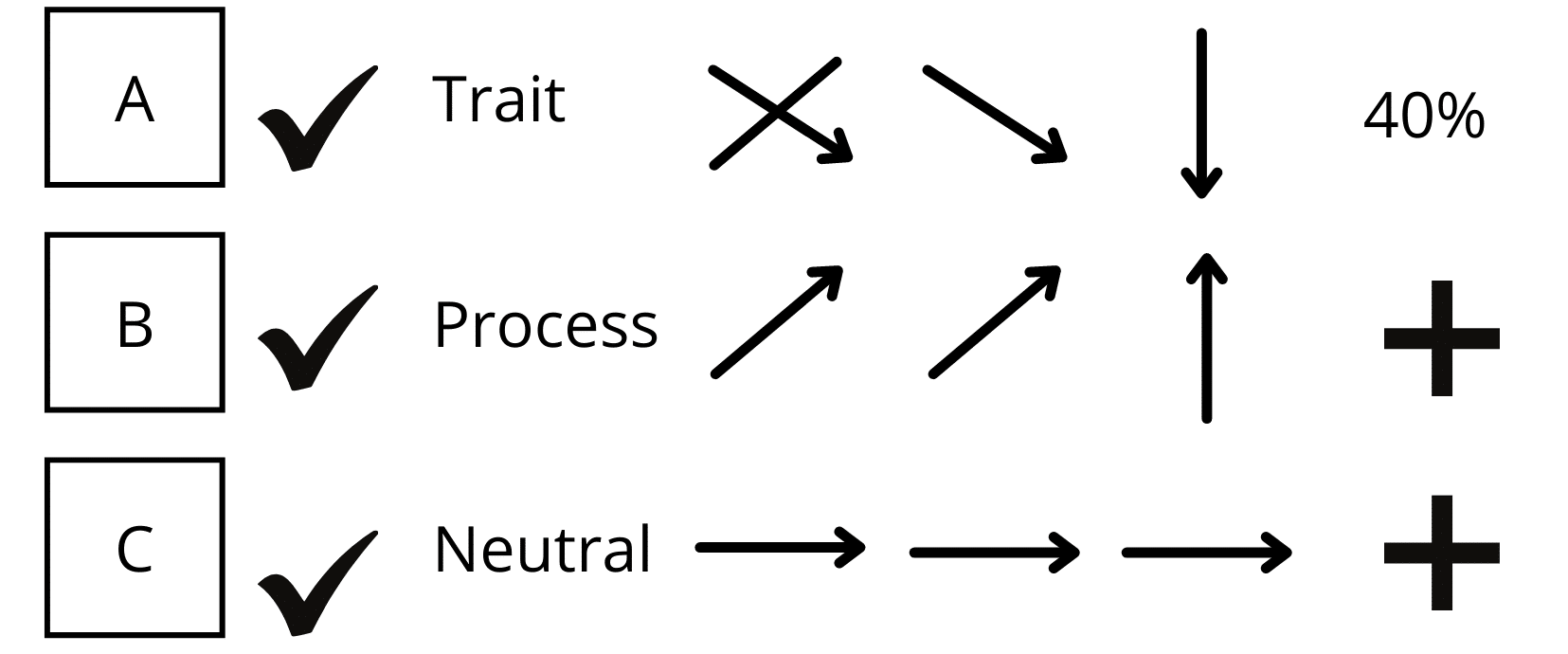

So I want to describe an experiment to you. And then I want to sort of challenge a little bit a potential ambiguity or confusion in Dweck that I think we can clarify by making use of this work from Stanovich. So Dweck did the following thing. She brought—she has a whole bunch of experiments, but let's talk about one. She brought in a bunch of school children and she randomly assigned them to three groups (Fig. 12a) (draws three squares vertically): group A, group B, and group C (writes A, B, or C inside each box respectively).

Fig. 12a

Mindset: Fixed And Malleable View

Now, Dweck talks about two different ways in which you can set your mind towards your traits. And the trait, it's really crucial, huh, and, this is relevant, is intelligence. So she talks about two views you can have. Two ways in which you can set your mind (underlines Mindset). Now it's a mindset because it's not just a belief, it's the way in which you identify with. It's the way in which you feel you are embodying the traits we're talking about. So you can have a fixed view (Fig. 13a) (writes Fixed beside Mindset) of your intelligence or a malleable view (writes Malleable beside Mindset). Okay. And so in the fixed view, you think intelligence is, like fixed, basically at sort of birth or early on. And then once it's locked in, there's not much you can do with it. So, for example, my height is a fixed trait. There's not a lot I can do to modify it. It's a fixed trait, okay? My weight is a much more malleable trait. I can change. It can—it's quite variable. It can change quite a bit. So you may think that intelligence is more like my height. You're sort of born with it. You're fixed. You got this number assigned and that's it. Or intelligence is malleable. It can develop and change.

Fig. 13a

Fig. 13a

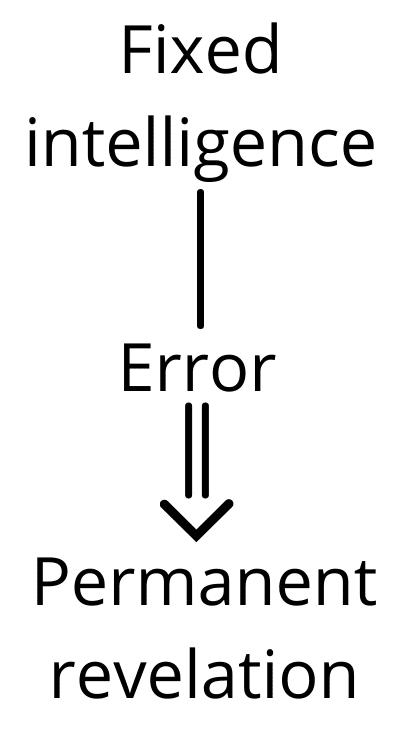

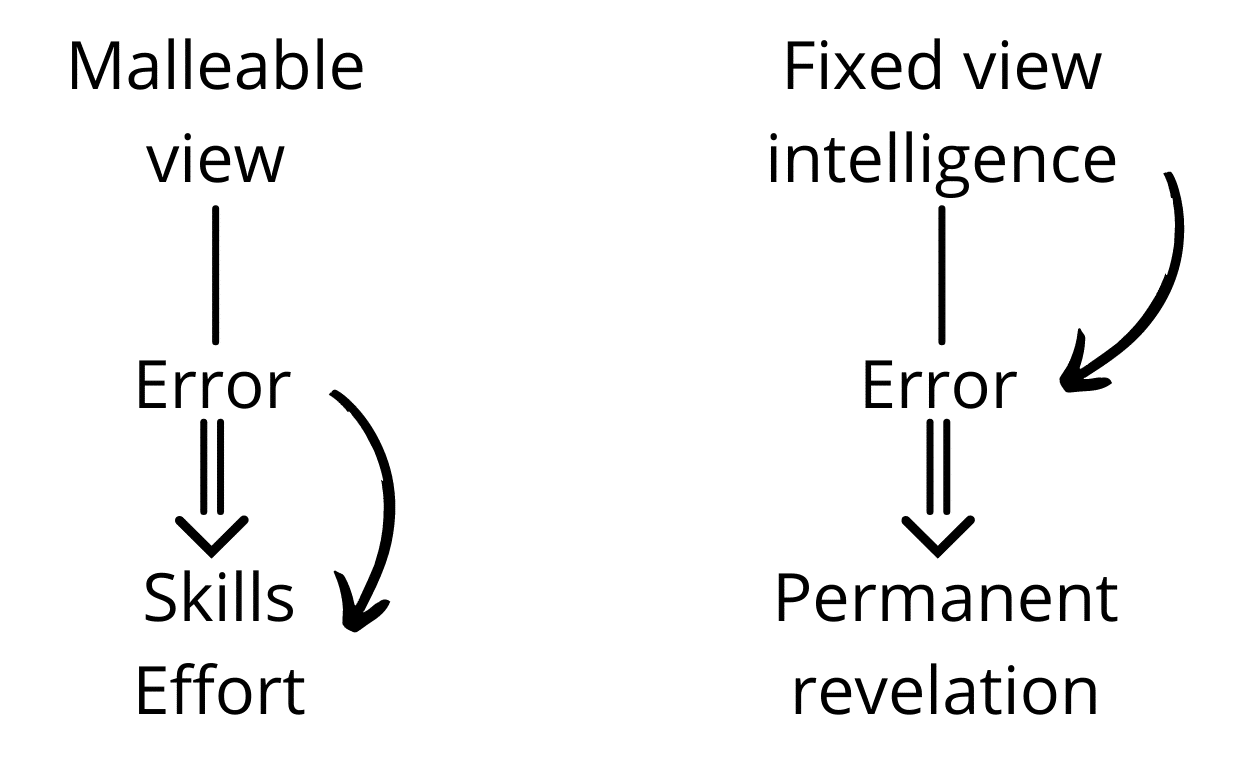

Now notice your behavior is going to be different if you think intelligence is fixed. If you think intelligence is fixed (writes Fixed intelligence), your attitude towards error (Fig. 14a) (writes Error under Fixed intelligence) is that error will reveal that you have a defect in a non-changeable trait. It'll reveal—it'll permanently disclose that you are not smart. So fixed intelligence tends to turn error into permanent revelation (draws an arrow from Error and writes Permanent revelation). If I make mistakes, that will show that I have low intelligence. And once everybody knows that, including myself, there's nothing I can do about it. And then I'm doomed to being a stupid person.

Fig. 14a

If you have the malleable view of intelligence (writes Malleable view beside Fixed intelligence, adds View to Fixed intelligence), error doesn't do that for you (Fig. 14b) (writes Error below Malleable view). Error doesn't see—error is now—oh wait, error points towards the skills I'm using. I need better skills or the effort I'm putting in (writes Skills and Effort below Error). I need to put in more effort because if it's malleable, I can do things to change it. So the error says the error is basically pointing, you need to make some changes. You need to cultivate more skills. You need to cultivate more effort. Now, notice something right away, please. Notice how the fixed view (draws an arrow from Fixed view to Error) focuses you on the product? It focuses you on—you just get fixated on the error. "Oh no." This (indicates Error under Malleable view) focuses you—remember the key of rationality? It focuses you on the process (draws an arrow from Error to Skills effort). The process.

Fig. 14b

Okay. So she has a lot of experiments showing that the fixed view and the malleable view have a huge impact on your behavior, but interesting thing, the way—how can you trigger people into this modal? If you were in sort of an authority position, like being a teacher at a school, the one way you can trigger the mode—and this is really a mode, right? The mode that people are in— is how you praise them, the kind of feedback you give them (Fig. 13b) (writes Praise above Dweck). If I praise you using trait language, like "You're so smart, you're so bright. That's going to tend to trigger this orientation (indicates Fixed view). If I praise you for the process, "Wow. You're really, you're using a really good skill. You're putting in a lot of effort for that." That's going to make the process salient to you. The more I make this (indicates Fixed view) salient, the more you're going to be in that mode. The more I make this (indicates Malleable view) salient, the more you're going to be in that mode. Okay. So I can praise the trait (writes Trait beside Praise), right. Or I can praise the process (writes Process beside Praise). I think about how important this is to parenting or schooling.

Fig. 13b

Fig. 13b

Okay. So let's go back to the experiment. We have these three groups (Fig. 12b), the C group is the control group. They're all given a set of problems that have been pre-tested for, I think they were grade 4. They could all solve these problems. They're challenging, but they're all solvable. They all solved them. So all groups solved them (checks each box). But group A is praised for its trait (writes Trait beside group A). Group B is praised for the process (writes Process beside group B). And then group C has given the neutral, just acknowledgement that, "Oh, the praises we used succeeded so well in that problem." Okay? So neutral (writes Neutral beside group C).

Fig. 12b

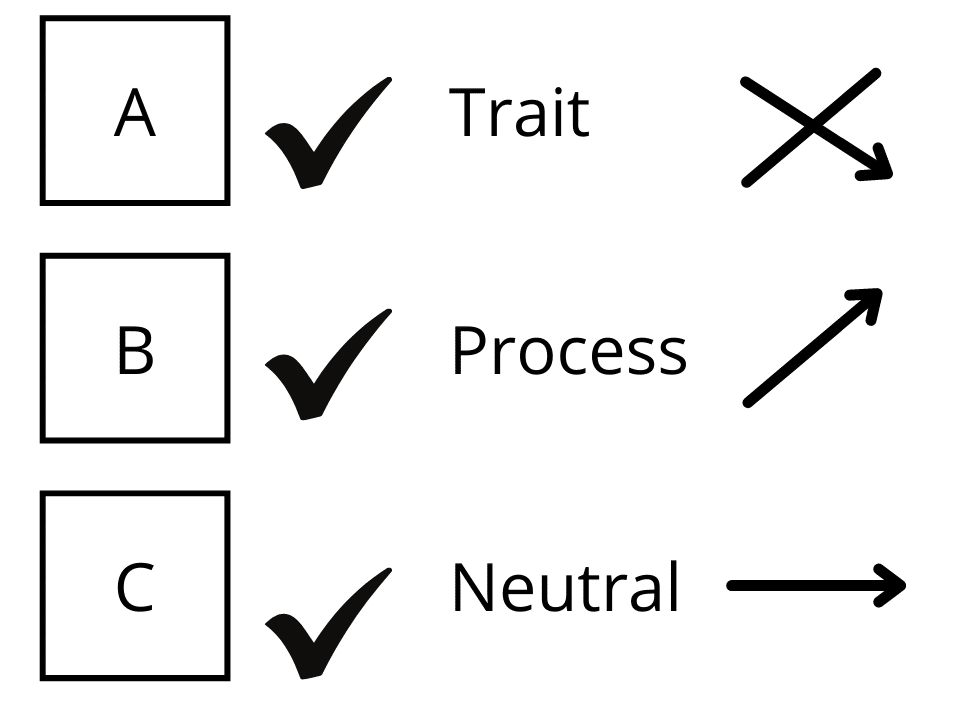

So the idea is this (indicates Trait) is going to trigger these people into the fixed view (indicates Fixed view), this (indicates Process) is going to trigger people into the malleable view (indicates Malleable view). So now what your do is, you give the kids a bunch of tests. You ask, which ones want to take on some more challenging problems. Notice what I'm doing here. I'm looking for need for cognition. Looking for need for cognition.

What I find is this group (Group A). Yeah (checks Group A but erases it again). Sorry, that was completely wrong. This group (Group A) says "No. I don't want to try harder problems (Fig. 12c) (draws a southeast pointing arrow and a line pointing northeast)." "Why?" Because if they try harder problems, there's a very good chance that they will generate error and then error will generate the recognition that they're less intelligent. And then they're permanently stained with that, permanently marked. The process people say, "Yeah, I'd like to try harder problems." (draws a northeast pointing arrow beside Group B). They have a need for cognition. C's to be triggered, of course, neutral (draws a horizontal arrow beside Group C). Right?

Fig. 12c

Then you give them some harder problems and ask, do they enjoy them? And the, "Oh, do not enjoy this." (Fig. 12d) (draws a southeast pointing arrow beside Group A) "Yeah, I enjoy this." Neutral (draws a horizontal arrow beside Group C). Now, here's the crucial thing.

Fig. 12d

Now you give them a set of problems that were equal in difficulty to the first set of problems. You give them a set of problems that were equal in difficulty to the first set of problem. This has all been massively pre-tested so it's safe. And what you find is this group does about the same (Fig. 12e) (draws a horizontal arrow beside Group C), this group does much worse, and this group does better than it did before. (Text overlay appears saying, "John means "Group A does much worse, Group B does much better!).

Fig. 12e

And now I want to, I want to extend this and notice how this is starting to fold into a kind of self-deception. Right? You ask these kids to write to—I believe the experiment was done in America. You ask these people to write to a student in Germany that they will never meet by the way and report how they did on the experiment. So these two groups (Fig. 12f) (draws a + sign beside Group B and C) largely tell the truth. They just took, you know. 40% of these people (writes 40% beside Group A) lie about their performance.

Fig. 12f

Okay. What am I trying to show you? I'm trying to show you the way you frame yourself, the way you identify with your processing has a huge impact on your problem-solving ability, your proclivity for self-deception and your need for cognition. Rationality is an existential thing. It is not just an informational processing thing.

Now. One thing that comes out of this is the question. Yeah, but is intelligence fixed or malleable? And Dweck is not quite clear about that. The evidence is pretty clear that there's a few things you can do to modify your intelligence. There's some suggestion that long-term mindfulness practice, by enhancing attention and working memory, can improve your measures of general intelligence. But by and large, intelligence is fixed. It's not that malleable. And then you may say, "Oh, then this whole thing is based on, you know, lying to the kids." Right? Basically getting them to relate to intelligence and something malleable. Not really, not really at all because what we're actually talking about here, and that's what I've been continually alluding to here is that something that is terrifically, there's a way in which intelligence is terrifically malleable.

And this is exactly what mindsetting is (Fig. 10a) (writes Intelligence and draws a circular arrow pointing to Intelligence) the way in which intelligence recursively relates to itself is a way in which we can think about it being rational, but that might—sorry, a way in which we can think about it being malleable. And my word slip shows you what my thinking is, a better way of talking about this is that intelligence is fixed (writes Rationality beside the circular arrow of Intelligence) and this is what Stanovich argues, but rationality is highly malleable. And then here's Stanovich's main point about this. We care too much for intelligence and not enough for rationality. Because, yes, intelligence is highly predictive of all these things. And that's why measurements of g are such powerful predictors. But if I wanted to know something about you now, following Stanovich's argument, I want to know not how intelligent you are (indicates Intelligence), I want to know how rational you are (indicates Rationality) and that is highly malleable.

Fig. 10a

Okay. So what I'm trying to show you is that rationality is an existential issue. It's about how you're identifying with your own cognitive processing and the way in which that identification process (indicates Intelligence) can impede how you're applying and using an intelligence, or it can enhance it. And then there's the possibility (indicates the circular arrow around Intelligence) of cultivating the right kind of recursion and identity, the right kinds of cognitive styles. So somehow we have to put processes of identification, processes of coordinating cognitive styles together, and we can get back a clear path for becoming much more rational. And as I'm suggesting to you therefore much more wise, because if we use rationality to better learn how to use rationality and identify with our rationality (Fig.10b) (draws a circular arrow around Rationality), then, of course, I'm suggesting to you that's wisdom (writes Wisdom). And as I promised, we should now next—we should now turn to some of the explicit, psychological theories of wisdom.

Fig. 10b

I can't, as I've already mentioned, I can't do all of them. I'm going to zero in on four theories that I think are quite representative of central ideas in the psychology of wisdom. And then I will then propose, I'll propose my theory the work I've done with Leo Ferraro. And I'll put that into sort of dialogue with these existing theories, as well as critiquing the theory the work that I did with Leo, and then ultimately what we want to do is resituate that account of wisdom into its connection with the cultivation of meaning and the pursuit of enlightenment. We will take a look at that next time.

Thank you very much for your time and attention.

Episode 42 Notes

Jonathan Baron

Jonathan Miller Baron is a Professor Emeritus of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania in the science of decision-making.

Dual processing theory

In psychology, a dual process theory provides an account of how thought can arise in two different ways, or as a result of two different processes.

Daniel Kahneman

Daniel Kahneman is an Israeli psychologist and economist notable for his work on the psychology of judgment and decision-making, as well as behavioral economics, for which he was awarded the 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.

Book Mentioned: Thinking Fast and Slow - Buy Here

Stephen J. Ceci

Stephen J. Ceci is an American psychologist at Cornell University. He studies the accuracy of children's courtroom testimony (as it applies to allegations of physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect), and he is an expert in the development of intelligence and memory.

Publication mentioned: Clue‐Efficiency and Insight: Unveiling the Mystery of Inductive Leaps

Gregg D. Jacobs, Ph.D

Book Mentioned: The Ancestral Mind: Reclaim the Power - Buy Here

John D. Teasdale

John D. Teasdale was a leading researcher at Oxford University, and then in the Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit in Cambridge.

Carol Dweck

Carol Susan Dweck is an American psychologist. She is the Lewis and Virginia Eaton Professor of Psychology at Stanford University. Dweck is known for her work on mindset.

Book Mentioned: Mindset - Buy Here

Robert J Sternberg

Robert J. Sternberg (born December 8, 1949) is an American psychologist and psychometrician. He is Professor of Human Development at Cornell University.

Book Mentioned: Why Smart People Can Be So Stupid - Buy Here

Keith E. Stanovich

Keith E. Stanovich is Emeritus Professor of Applied Psychology and Human Development, University of Toronto and former Canada Research Chair of Applied Cognitive Science.

Book Mentioned: What Intelligence Tests Miss - Buy Here

Other helpful resources about this episode:

Notes on Bevry

Additional Notes on Bevry