Ep. 40 - Awakening from the Meaning Crisis - Wisdom and Rationality

(Sectioning and transcripts made by MeaningCrisis.co)

A Kind Donation

Transcript

Welcome back to Awakening from Meaning Crisis.

So last time, I tried to make some tentative suggestions as to what religion that's not a religion would look like. And how it can make use of and be integrated with ecology of psychotechnologies for addressing the perennial problems and a cognitive scientific worldview that can legitimate and situate that ecology of practices.

And then I made some suggestions as to the relationship between Credo and religio in our determination of our mythos and the issue of criterion setting. I made again, another argument for open-ended, in that sense, Gnostic mythos. Talked about a mythos that always puts therefore the credo in service of the religio. And that is always directed towards top-down, the propositional being ultimately grounded in the participatory, and also affording the emergence up out of the participatory through the perspectival and procedural into the propositional. I've suggested some ways in which we might set up a way of engineering credo, something analogous to a Wiki and create a structure that is distributed. A co-op structure facilitated by things like the internet.

And so, again, [I] remind you, I was not trying to offer anything definitive or set myself up in any kind of way. That is not what I want to do. I want to try and help facilitate the people who are already doing this so that they have ways of talking to each other, coordinating with each other and facilitating each other's development and growth.

I then turned towards one of the culminating things we need to do, picking up on one of the deepest relationships between meaning—sorry, one of the deepest relationships that meaning has, which is the relationship between meaning and wisdom. We need wisdom, of course, to, as I've argued, because it's the meta-virtue for the virtues. And we need that in order to give the individual pool for the relationship with the collective creation and cultivation of the meta-psychotechnology for creating the ecology of psychotechnology. We also, of course, need wisdom before, during, and after the quest for enlightenment, the quest for a systematic and reliable response to the perennial problems.

Insight: Systematic Seeing Through Illusion and Into Reality

I then proposed to take a look at the cognitive science of wisdom. And we did that by taking note of an important article that comes out, sort of, after the first decade and a half of the resurgence of scientific interest in wisdom. And that's the article of McKee and Barber, and they're doing something consonant with what we've been trying to do in this series. They're trying to, in a sense, salvage what we can from the philosophical theories, the legacy and the Axial Age of wisdom and the psychological theories that were emerging at that time. And then they set them into dialogue with each other, a process of reflective equilibrium trying to get a convergence between them. And they argue that all of these theories, the philosophical and the psychological theories converge on a feature, a central feature of wisdom. And then following work that I did with Leo Ferraro in 2013, we can sort of expand beyond the explicit thing to what is also set alongside their phrase and also directly implied by their phrase. And so a central feature of wisdom is to systematically—sorry, the systematic seeing through illusion and into reality, (Fig. 1a) (writes systematic seeing through illusion and into reality) at least comparatively so. And this, (places a bracket underneath Seeing through illusion) of course, is insight, (writes Insight under the bracket) but it is a fundamental insight. (draws an arrow from Systematic to Insight) It is a systematic insight. It is an insight, not just into a particular problem, but into a family of problems.

Fig. 1a

And McKee and Barber make use of a point that I made use of when I was talking about: systematic insight in higher states of consciousness. They make use of the work of Piaget. If you remember Piaget found systematic errors in the way children are seeing the world, remember, things like, they fail at conservation tasks, counting numbers, or pouring liquids, right? So you have these systematic errors, which reflect a systematic way in which the children have over-constrained their cognition, their—they have to constrain their cognition it's adaptive, but they have to go through that process of assimilation and accommodation, constantly optimizing and complexifying their system of constraints.

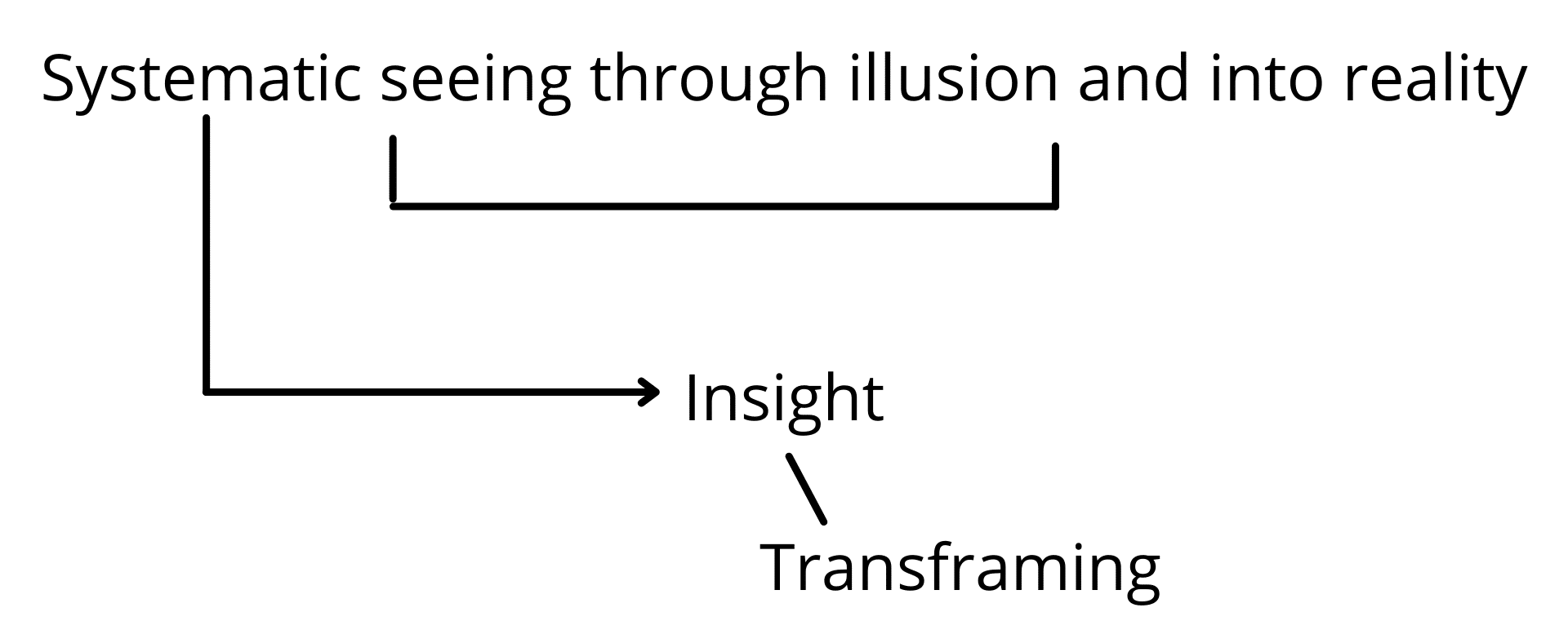

But what we see with the children is eventually they get a systematic insight and we've all done it. We go through qualitative change, qualitative development. There's an actual change in our competence. Because it's not an insight into this problem or this instance where I'm failing to conserve, or this instance, or this instance where I'm egocentric, or this instance, but it's a[n] insight into failures of conservation as a kind of error. Failures of egocentrism as a kind of error and having a[n] insight that is not just at the level of framing, but at the level of transframing, because it not only is reframing the problem. It is transforming my competence so it is a transframing insight. It is a systematic insight. (Fig. 1b) (writes Transframing below Insight) Because what it gives you is sensibility transcendence.

Fig. 1b

Fig. 1b

That's literally what's happening to the children. Their sensibility is going through a form of transcendence. That's exactly what development is. And they use that as a way of explaining what they mean. Of course, without realizing it they're making use of one of the paradigmatic metaphors for talking about wisdom. Which is, as the child is to the adult, right? (Fig. 2) (writes Child : Adult) The adult is to the sage (writes Adult : Sage below Child : Adult). Just like the adult has had systematic transframing, gone through development so that in a way, compared to the child, they much more systematically see through illusion and into what's real, the sage, right, similarly in comparison to an adult, right, sees systematically through in a transframing fashion, illusion and into reality.

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

So this a core constitutive feature of what it is to be wise. And you can see something, and this is not something that McKee and Barber said, okay, but you can see how this (indicates Transframing) is automatically, I would argue—I would argue; they're not, but I would argue, this is automatically, you know, connected to the project of enlightenment in some very important fashion. Alright.

Wisdom vs. Knowledge

What are a couple of other important things that McKee and Barber talk about? They talk about that wis—and this is the beginning of the important distinction between wisdom and knowledge that we've been sort of also making use of throughout the course, that wisdom is not about what you know, wisdom has to do with how you know it.

And there's two senses of How that I want to explicate that they leave rather implicit, right? There's how you know it is, how you have come to know it; what's the processing involved as opposed to the product? So wisdom has a lot more to do with the process (Fig. 3) (writes Wisdom - Process) than with the product. (writes Product) Knowledge is often the product, "I know—this is what I know, and I know this and this and this," but wisdom is, "How am I knowing? How am I knowing?" Right? So definitely that. And that's going to be pivotal because—and that's going to immediately link wisdom to rationality because one of the key features of rationality, I've mentioned this before—we're going to come back to this—the work of Stanovich; is a rational person is not only fixated on the products of their cognition, they pay attention to and find value [in] the processing of their cognition. That's what it is to be rational. Right?

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

So that's one aspect of what they mean by the How, and then there's another aspect of How you know. And that has to do, and this goes to a point made by Kekes between descriptive—John Kekes. (Fig. 4) (writes Kekes) Excellent. Philosopher does work on wisdom, right? But Kekes makes a distinction between descriptive knowledge (writes Descriptive knowledge) and interpretive knowledge. (writes Interpretive knowledge) I often prefer to use the word knowing rather than knowledge, but that's his way of talking about. So again, this is (indicates Descriptive knowledge) grasping the facts, whereas interpretive knowledge this points towards an aspect of wisdom that we're going to have to come back to. This has to do with understanding. (writes = Understanding beside Interpretive knowledge) This is to grasp the significance of what you know. (writes Grasp the significance below understanding) And of course, relevance realization is being invoked. They're grasping the significance, right? Connecting to the relevance realization, so understanding is grasping the significance. So part of what we're talking about with wisdom. And we're talking about the how, rather than the what you know. We're talking about the process rather than the product and we're talking not about the description of the facts, right? But we're talking about you grasping—understanding by grasping the significance of the facts that you have.

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

So wisdom has to do with these things. It has deep connections to understanding (indicates Understanding), again, which has to do with the relevance realization. It has to do with the process (indicates Process) rather than the product (indicates Product), right. And that is all tied into this (indicates Systematic seeing through illusion and into reality) systematic transframing realization of what's real.

Perspectival and Participatory Aspects of Wisdom

They then point to one other important feature of wisdom. They point out: there's a perspectival participatory aspect to wisdom. They talk about what's called a pragmatic self-contradiction. A pragmatic self-contradiction is not a contradiction in what you state (indicates Descriptive knowledge), it's a contradiction in how, in the perspective from which you make the statement and the identity, the degree of identity you have in making the statement.

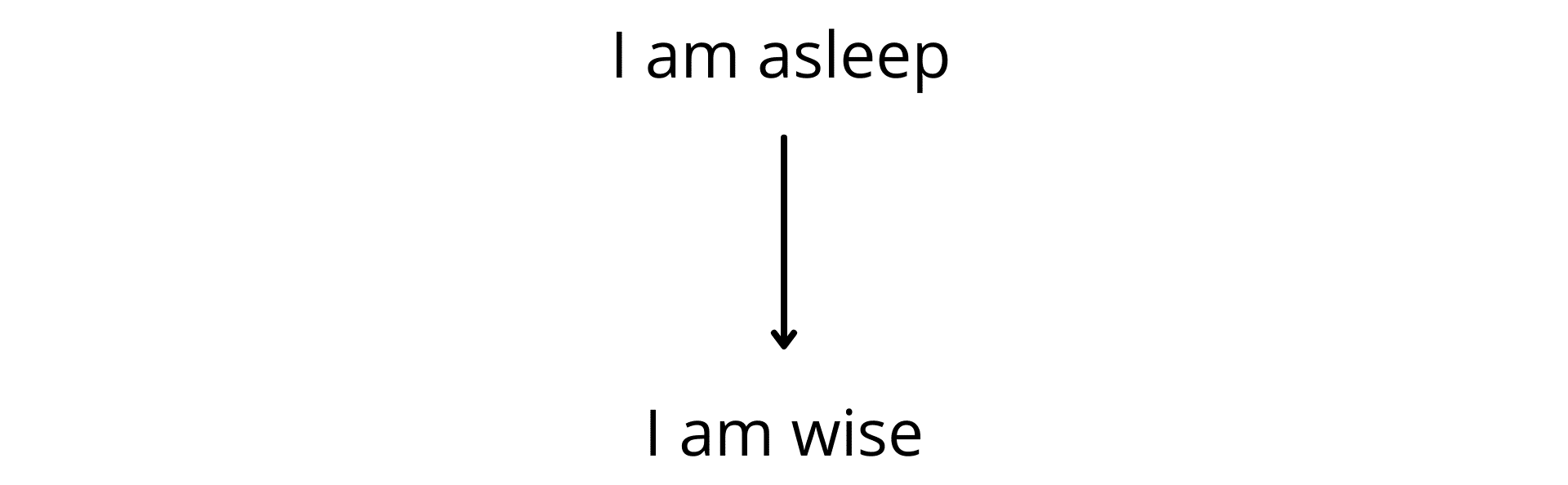

Let me give you a non-controversial example. Okay. So I am asleep (writes I am asleep). There is nothing logically wrong with that. If I'm pointing to the fact of John being asleep, you can—there's no conceptual contradiction in John being asleep. This is a pragmatic self-contradiction because uttering it means I'm uttering it from the perspective of somebody who is awake. Because I have to be awake in order to say it. And of course, there's a sense in which I'm not just pointing out a fact, I'm actually pointing to myself with it. And that's, of course, the degree to which I'm participating in the fact that's being disclosed. Now, that's very different, by the way, from lucidity in dreaming where people can realize in a dream that, "Oh, I am dreaming," right? Because you can realize you're dreaming and remain in the dream. There is nothing pragmatically self-contradictory about that.

Now they point out and think—you can just hear Socrates in this. They point out that this "I am wise" (Fig. 5) (draws an arrow from I am asleep and writes I am wise) carries with it a sense of very strong intuition of a pragmatic self-contradiction. To state that you are wise seems to be an indication that you are in a perspective, and you have an identity that is precisely not that of being wise. And, of course, this is part of the Socratic, you know, "I know what I don't know" idea.

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

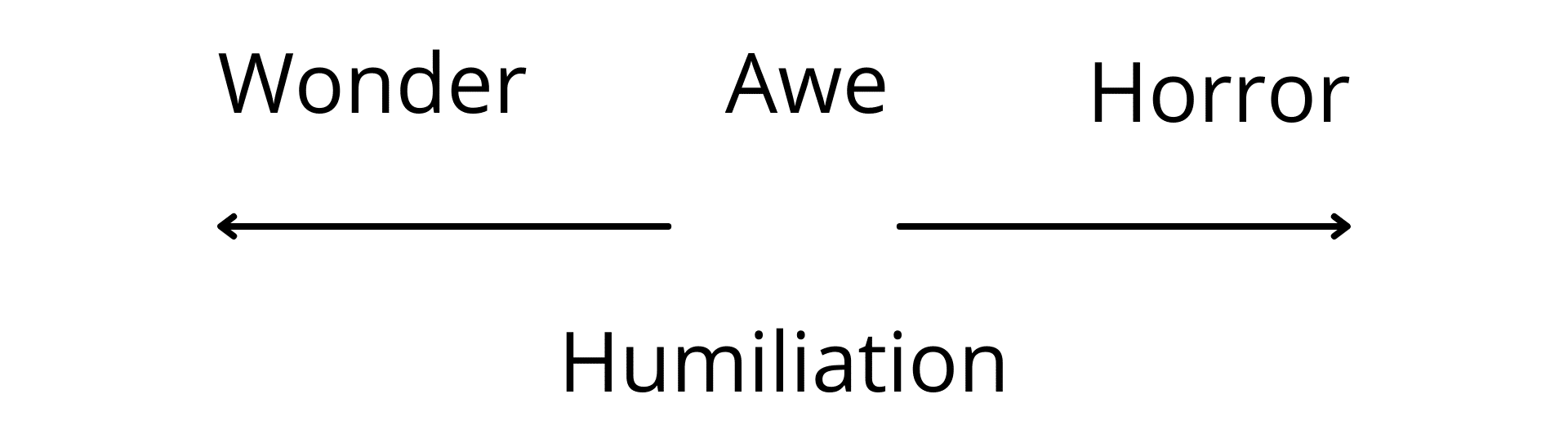

This is part of, again, how I've argued and this is why awe—Awe as this two-faced thing between horror and wonder, (Fig. 6) (writes Wonder, Awe, and Horror and draws two arrows pointing to the left and right) right? And that, what it does is it brings out, and again, I'm using this in the original meaning of the word, not what we mean by it now—humiliation, the inculcation of humility.

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

And so what that tells us right away is that wisdom has this perspectival and participatory aspects to it such that it's not a matter of making, of even having true beliefs (gestures at I am wise). There's a matter of: what perspective can you take? What perspectives? What identities are you assuming and assigning? So the participatory and the perspectival are also very central to wisdom. And that, of course, makes sense, again, with wisdom having to do with much more with the How than the What.

And, of course, this (indicates Systematic seeing through illusion in Fig. 1b) is also perspectival and participatory because I'm seeing through a misframing and I'm going through transframing. I'm actually going through developmental change. My world is opening it up and I in a coordinated resonant manner. I'm opening up to it and opening up through it, which is, of course, what wonder and awe are all about.

Rehabilitating What It Means To Be Rational

Okay (erases the board). So that gives us some very important things to take note of. And I've already indicated a connection to Stanovich with the idea of paying attention to process rather than product. And we can strengthen that connection by noting that at the core of wisdom is the capacity for overcoming self-deception. Now Stanovich himself has published about, at least, overcoming foolishness and therefore, at least by implication, what it is to become wise. But he normally talks about this ability to systematically overcome self-deception with another term. And this is the term rationality (writes Rationality). And throughout I've been proposing to you that part of what we need to do to rehabilitate wisdom is we also need in a coordinated fashion to rehabilitate what it means to be rational. Rational does not, cannot be reduced to, cannot be equated to a facility with syllogstic reasoning. Okay. Rationality cannot be reduced to logic.

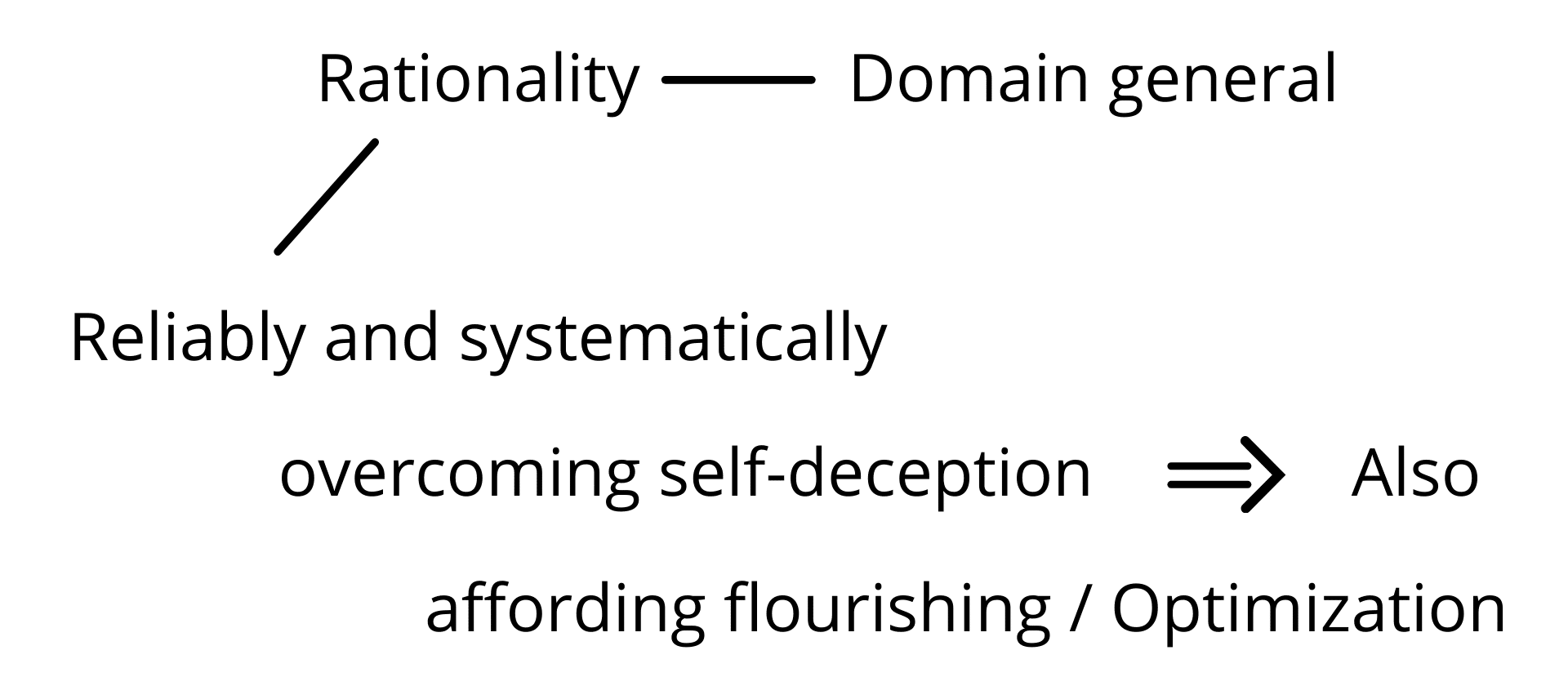

So let's broaden the notion right away and make it connect to what we're talking about, which is what we mean by rationality is a capacity—capacity to overcome self-deception in a reliable manner. So what I'm going to mean by rationality is reliably and systematically (Fig. 7a) (writes Reliably and systematically)—I'll [explain] what I mean by those in a sec. Overcoming self-deception (writes Overcoming self-deception). And this is also in a lot of the work on rationality, especially by people like Stanovich, and also affording flourishing (writes Affording flourishing/ optimization), which is afforded by some process of optimization of your cognitive processing.

Fig. 7a

Fig. 7a

Okay. What I mean by reliably, it can't operate according to a standard of perfection, completion, certainty. Reliably does mean, though, that it has a high probability of functioning successfully. Systematically means it's not operational just in this one domain (Fig. 8a) (draws a square). So let's compare rationality with expertise, okay? I can become an expert in, let's say, tennis. I'm not—Is tennis one n, I believe, my distraction is bad today (writes Tennis). Let's whatever. Maybe it's two n's. I can become an expert in this. Okay. We have to be careful ‘cause we equivocate on this term (writes Expertise). There is one in which we can—it's something that we can study and one in which this is just a synonym for being good at something (writes Being good at something below Expertise). Okay. I'm not using it in that sense. Okay. I'm using it in the sense in which it makes sense to say somebody is an expert in tennis, they have acquired a high proficiency in the set of skills, such that they have an authority about tennis playing. Okay, that's what we mean—you can become a legal expert, et cetera. Okay. So let the person—there is two n's in tennis. My brain is settling down. Okay. Or in the law (writes Law connected to the square), for example, to become a legal expert.

Fig. 8a

Fig. 8a

So what happens in expertise is precisely this. You find a domain, (indicates the square in Fig. 8a) a bounded domain that has a reliable set of very complex, very difficult, but nevertheless, reliable set of well-defined, or at least well definable for you eventually, set of patterns and problems. You know it's expertise precisely because it doesn't transfer. My expertise in tennis won't transfer even to things that are close. In fact, (draws another square beside the first square) it will interfere with when I try to play squash. (Fig. 8b) (writes Squash below the square) My expertise in golf will interfere when I try to play hockey. Not only does it not transfer, it will often interfere in [-] even to things that are relevantly similar to your area of expertise.

Fig. 8b

Fig. 8b

Now, this is a way again, (indicates the squares in Fig. 8b) in which we have to, we have to pay more attention in ways in which we could bullshit ourselves because we often confuse, right? Because we don't pay careful attention to how we're using similarity, we often confuse people's expertise. What do I mean by that? So here's somebody who's an expert, for example, in a particular domain, maybe in physics, they have expertise there. And of course, physics is about knowledge and about getting at what's real. And so that seems to be similar to, you know, philosophy, right? And so presumably somebody in physics can therefore just transfer their expertise to philosophy and just make pronouncements about philosophy and metaphysics, perhaps pronouncing that philosophy is dead or useless or some such thing, which of course itself is a philosophical statement and pragmatically self-contradictory. And if we don't pay attention to this fact about expertise, we may fail to see that the similarity between physics and philosophy may actually be good reason for believing that these people are the worst people to listen to for philosophical advice because their expertise in physics may be in fact, interfering with expertise in philosophy, for example, at least academic philosophy. Just the way that expertise in tennis actually interferes with you trying to play squash. Okay.

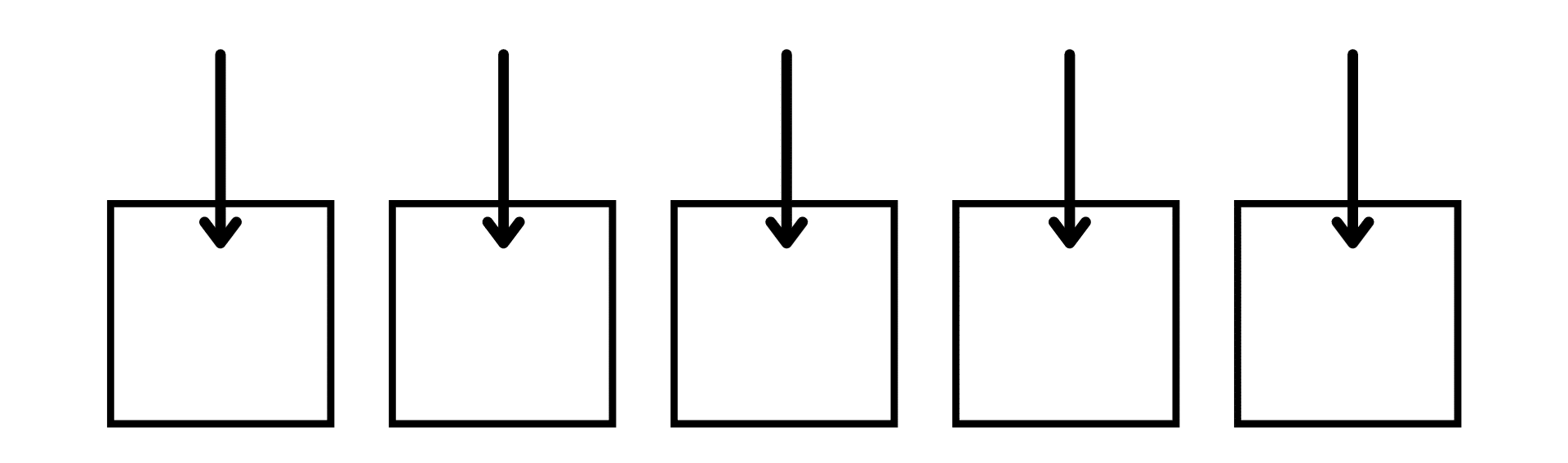

So expertise is not systematic. It is limited in its domain. Rationality (draws 5 squares) is supposed to apply within, it's supposed to be apt within each domain (Fig. 9) (draws lines into each square) and apply across many domains. Somebody is rational if they can know self-deception when they're doing their daily life, where they're doing their professional work, where they're engaged in friendship, where they're engaged in rational—sorry, romantic relationships, okay? So. (erases Fig. 9)

Fig. 9

Fig. 9

And this is an important thing to remember. Rationality is in this sense, a domain general notion, (Fig. 7b) (writes Domain general beside Rationality) as opposed to a context specific. Expertise tends to be a domain specific. Now, of course, this is a continuum. The more systematic somebody is, the more rational we can claim them to be. Somebody might be very rational in a couple of domains and irrational in others. So on balance, they're not that rational of a person, right? And, of course, I'm not claiming that everybody is rational in the domain general way. I'm claiming that that (indicates Domain general) is the achievement that we are aspiring to.

Fig. 7b

Fig. 7b

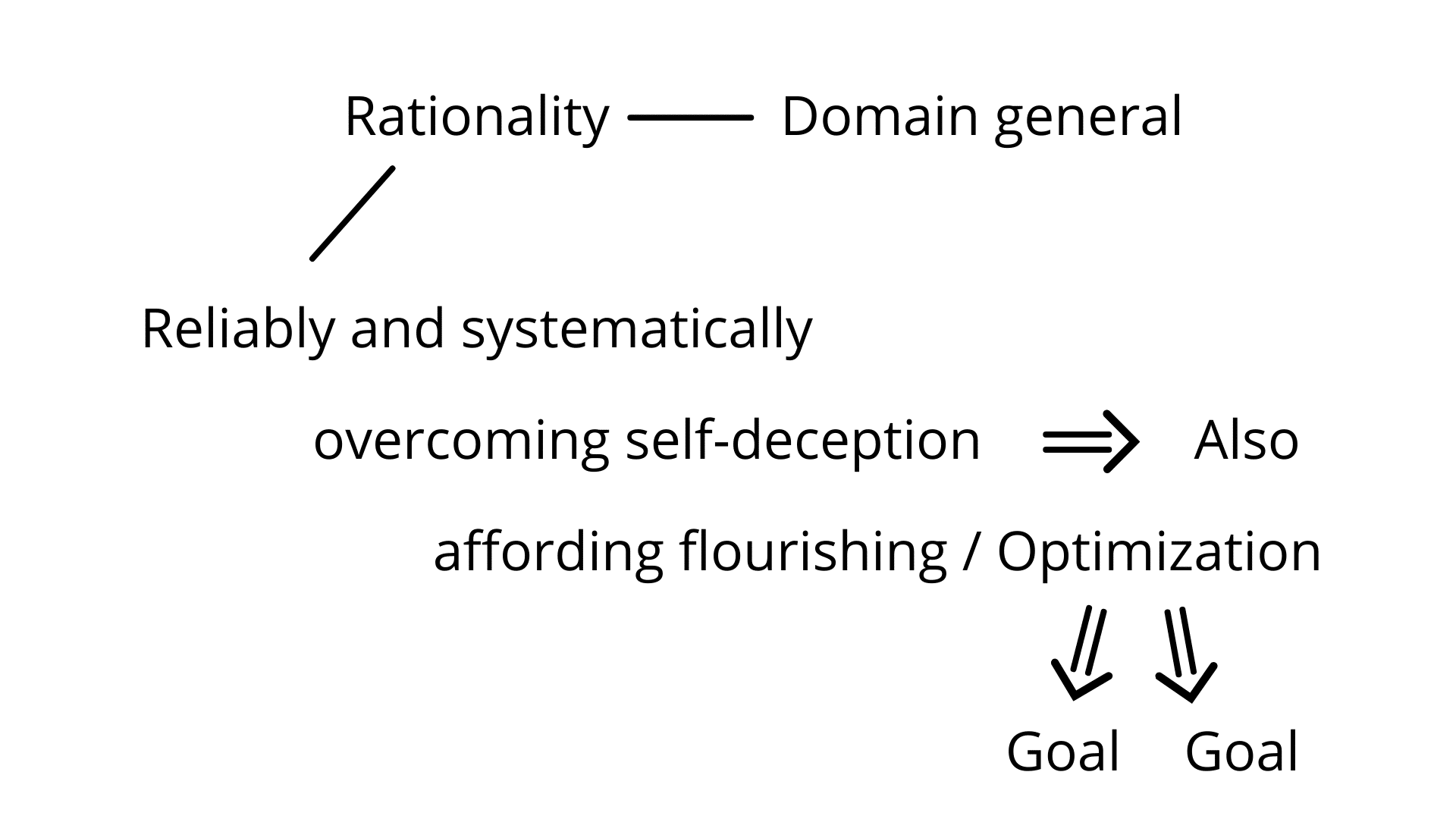

So rationality is to reliably and systematically overcome self-deception, also affording flourishing optimization. So you optimize (draws a downward arrow from Optimization) a set of procedures for achieving the goals you want (writes Goal below Optimization), but—And Stanovich doesn't talk enough about this, other people talk about this when they talk, like Agnes Callard, when she talks about aspirational rationality, part of it is also as you start to optimize your cognition, it will also tend to shift and change (Fig. 7c) (draws another arrow from Optimization and writes Goal) the goals you are pursuing. So the goals also tend to come under revision as we pursue this reliable and systematic overcoming of self-deception and the attempt to optimize our functioning so that we can afford flourishing. (erases the board)

Fig. 7c

Fig. 7c

Okay. So given that that's what—talking about. We can then take a look at Stanovich's work and other people's work. And the way to do this is to situate it within the cognitive science of rationality. And that is to take a look at the rationality debate (writes Rationality debate).

Experiments on Rationality

Okay. So the rationality debate was driven by a whole bunch of experimental results (draws arrow pointing to Rationality debate and writes Experimental results at the tail end) that seemed to show that human beings are irrational. Okay. And how that works is—I'm not going to go into this in great length and I recommend you read Stanovich's work. I'm just going to show you a couple of examples of the kind of experiments you do, and then show you the features of them. So you give people certain problems to solve. And then you will note certain things about how they solve them.

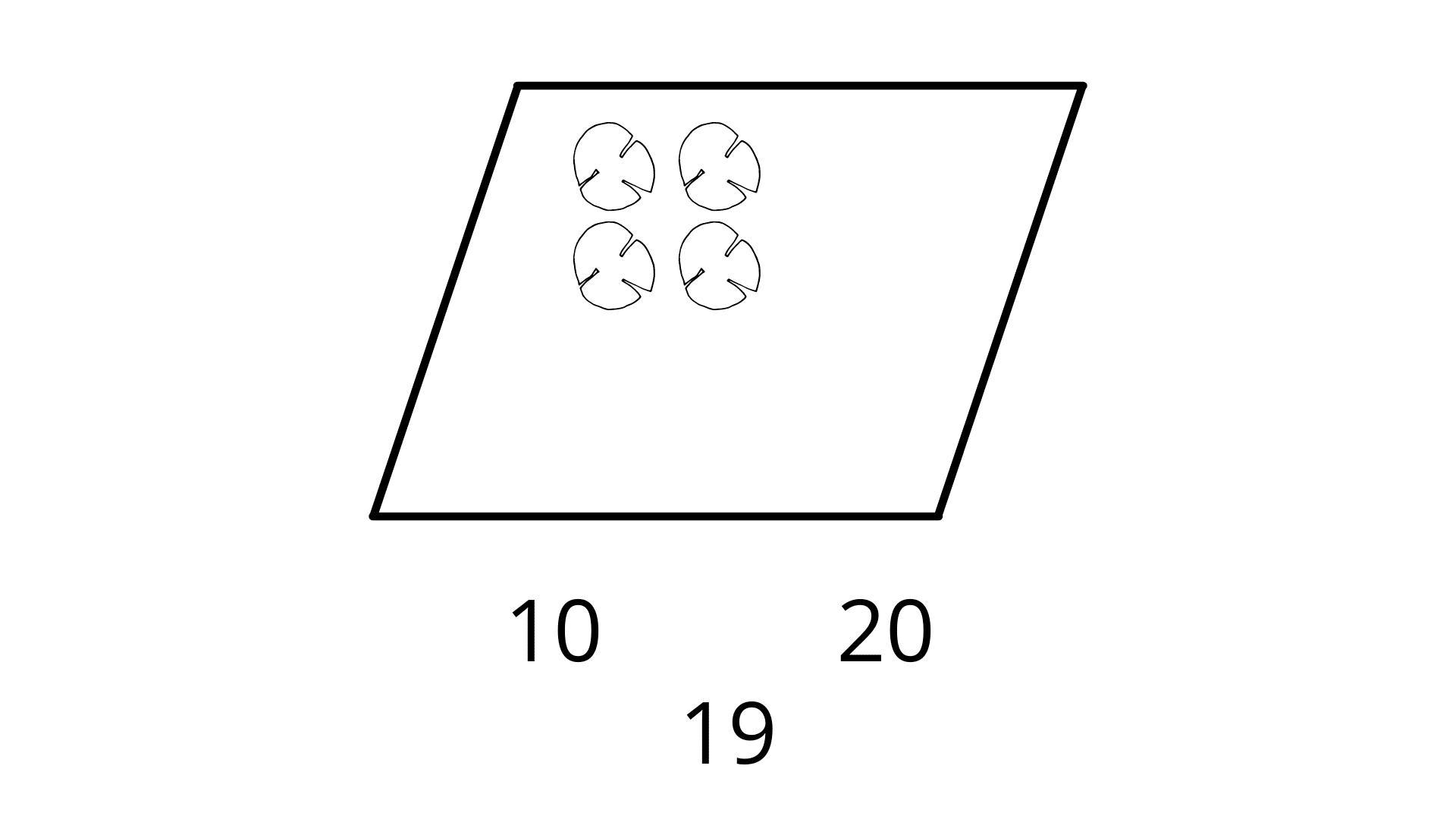

So here's one problem, right? So here's a pond of water (Fig. 10) (draws a parallelogram) and I'm covering it, right. There's lily pads growing on, it starts with one lily pad (draws a circle inside the paralellogram), and every day, the lily pads double. (draws three more circles) So on day one, there's one; day two there's two, and so forth. Every day, the lily pads are doubling. And then I tell you on day 20, (writes 20) the surface of the pond is completely covered. On what day was the pond half covered? And people say, "Oh, on the 10th day (writes 10) halfway through it's half covered." No. Right? On day 19 (writes 19), the pond is half covered because on day 19, I'm one I'm halfway, right? Oh, you have to ask yourself on day 19, I was halfway towards being full because doubling of half is what gets me full. So it's on day 19 that the pond was half-covered by the lily pads.

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Now what's interesting here is notice how the machine—there's machinery like your insight machinery. There's machinery that's making you leap to a conclusion. It sounds—it feels like an insight, but it's actually causing you to misleap. And we talked about this. You're jumping to a conclusion that's actually incorrect. Now, please note that how that adaptive machinery that often causes you to have an insight is actually thwarting you in an important way.

So people reliably fail on this kind of thing, right? (erases the board) This kind of task or you can give people this kind of task, you can get them to—You give a preliminary test and you find propositions that they strongly agree with or strongly disagree.

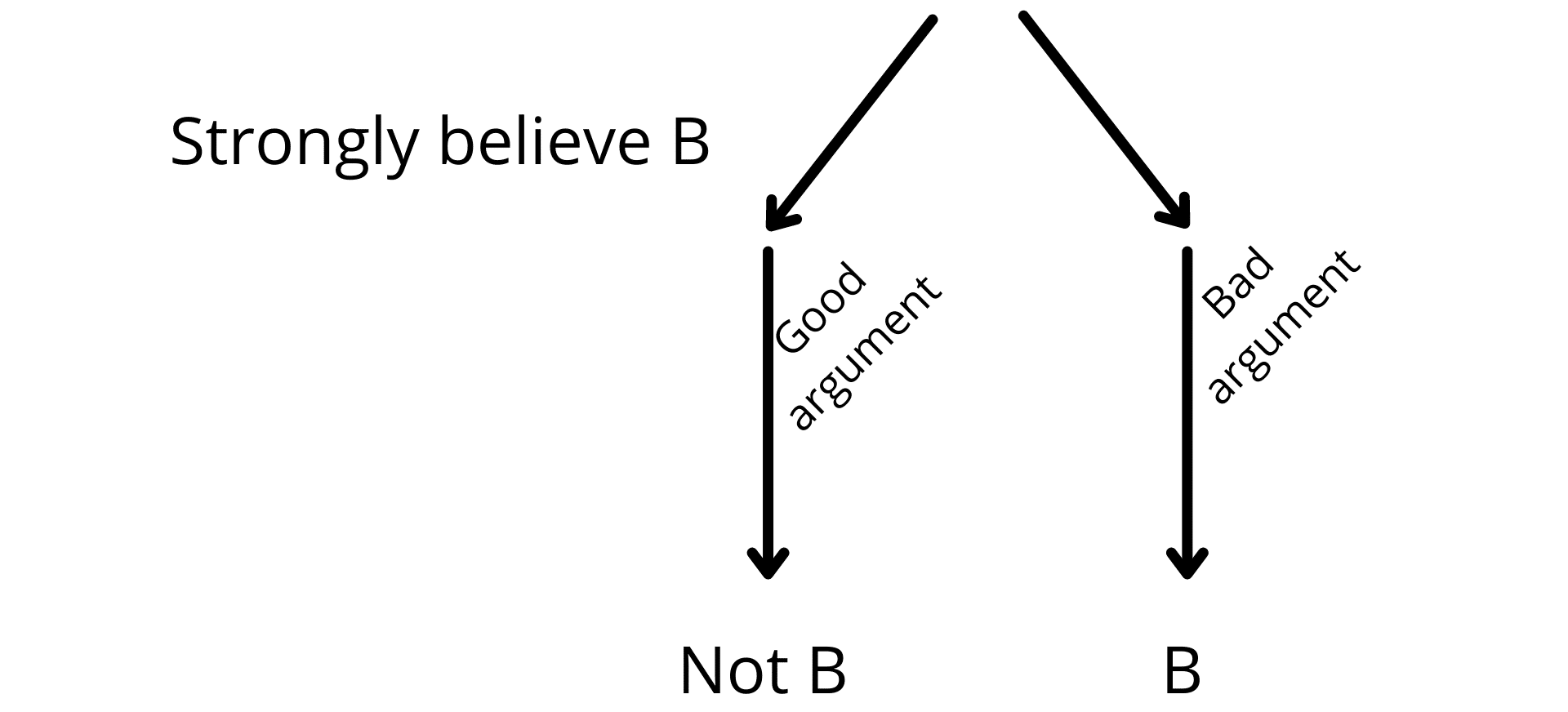

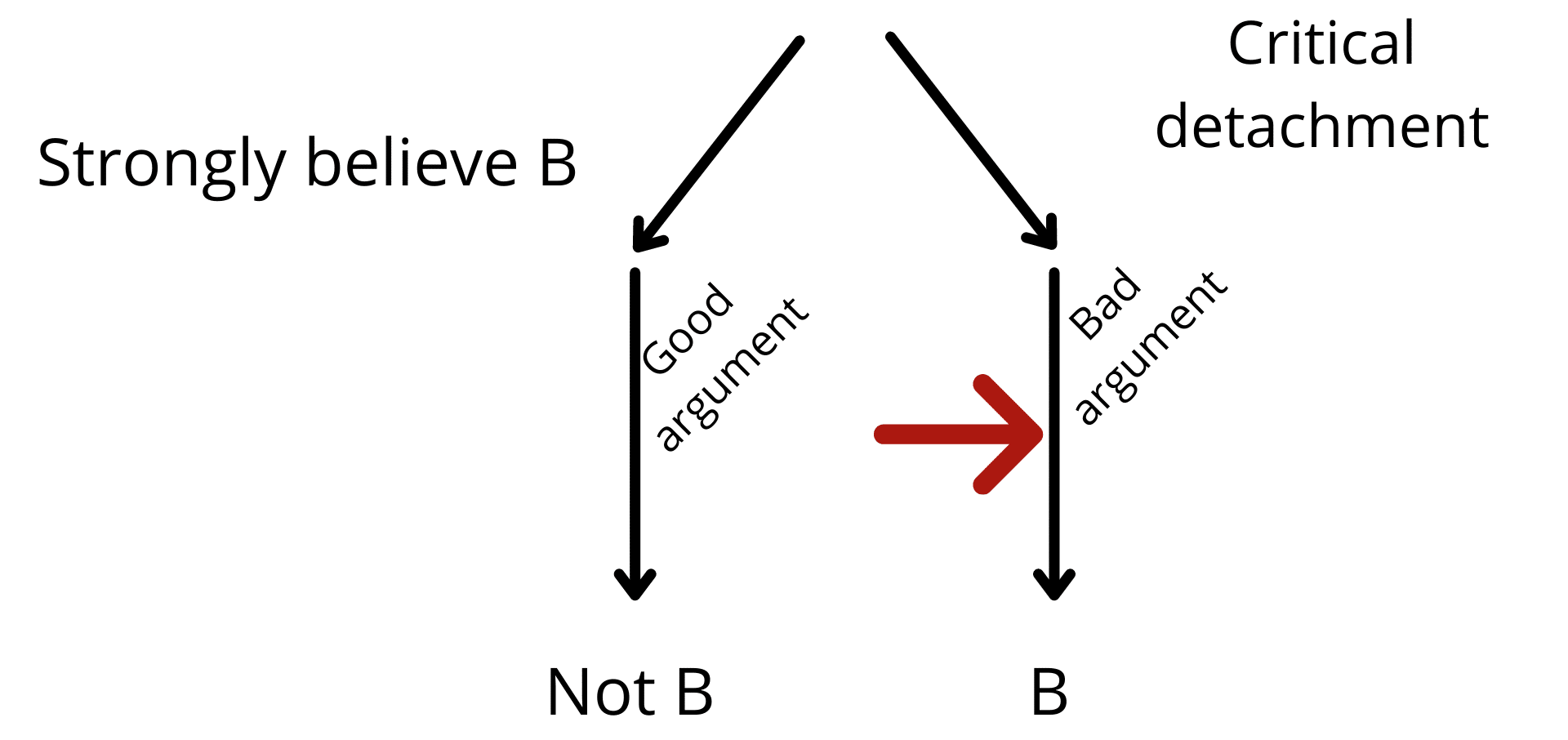

So let's say that some person strongly believes B. (writes strongly believes B) Well, you know, I'm not taking [a] stand here on this particular issue—they strongly believe that abortion is wrong or they strongly believe that capital punishment is wrong. Now, what you do is you give them two situations. (Fig. 11a) (draws a downward arrow) You give them a good, in the sense of a logically valid argument (writes Good argument beside the arrow) that leads to not B, (writes ~B) that (points to ~B) means not. Let's put not in here. (erases ~B and writes Not B) And you give them a bad, (draws a downward arrow parallel to the first arrow) very poorly constructed argument (writes Bad argument) that leads to B (writes B at the bottom of the arrow) and you ask them, "Take a look at this and tell me which one of these is a good argument (draws arrows pointing the first 2 arrows from above)."

Fig. 11a

Fig. 11a

And notice what I said earlier, how this points to what Stanovich argues that part of rationality is your ability to remove your fixation (continuously taps on Not B) on the product of your cognition. That's like being locked in the nine-dot problem, right? And be able to direct your attention and care about the processing (taps Good argument) for its own sake. This is critical detachment (writes Critical detachment). And what you find reliably for many people is people will say, "Oh, well, this is the good argument. This is the good argument (Fig. 11b) (red arrow appears pointing to Bad argument)." They'll fail at critical detachment (erases the board).

Fig. 11b

Fig. 11b

Now here's the thing. I'll give you a couple more of these, but notice when I showed you the right answer and the pond example, you went, "Oh, yes! Of course, of course." So you acknowledge the principle you should be using, but you don't actually reliably apply it. So you know what the right reasoning principle is, but you don't reliably apply. You know, you know that I should be able to independently evaluate an argument (draws a downward arrow and writes Good argument beside it) independent of what it leads to (draws a circle below the downward arrow), because if I can't do that, then there is no rationality possible because if you can't independently evaluate the argument, then you can't use the argument to evaluate the conclusion. And therefore I could never persuade you by argument. So you know that you should evaluate the argument independently from the conclusion, but we reliably failed to do that.

Do you see what the pattern is? We know what the principle is. We acquiesce in it when it is stated to us, but in experiment after experiment, we reliably fail to do it. Let me get you one more example. There are so many of these look up the conjunction fallacy, look up confirmation bias, look up the Wason selection task. Some of you can read some of my work elsewhere. I'll give you one more example of this, just because it's again so interesting about this.

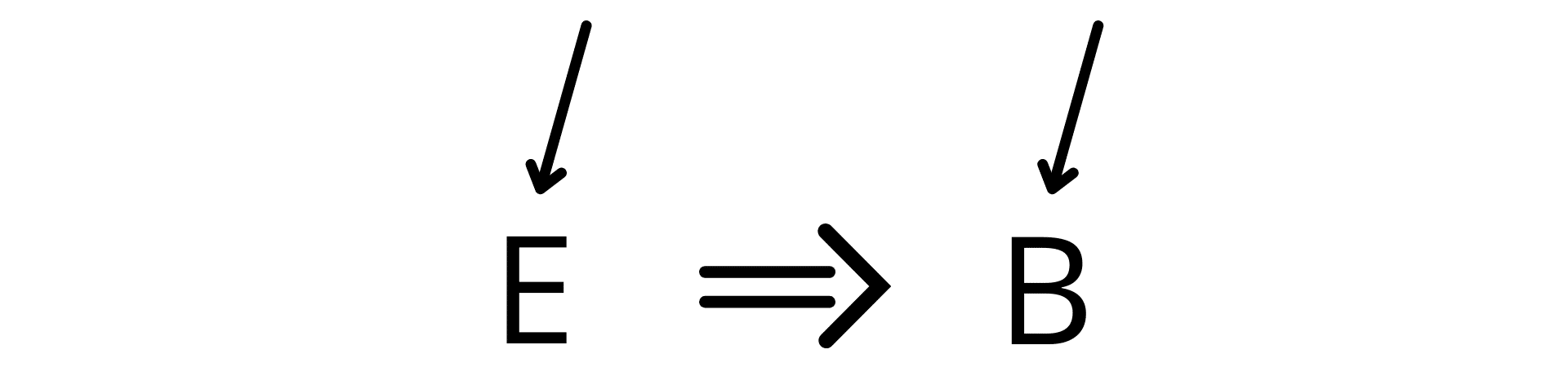

So here's a principle we all acquiesce in I believe. 'Cause whenever you ask people, they say "Yes, yes, of course. That's the rule we should be using." Here's the rule. So I've got some evidence (Fig. 12) (writes E) and the evidence is the basis for my belief (draws an arrow pointing away from E and writes B). And then if the evidence is undermined (draws an arrow pointing to E), I should change my belief (draws an arrow pointing to B). Of course, right? (erases the board)

Fig. 12

Fig. 12

Now, of course, we can have disputes about what counts as evidence and blah, blah, blah, but that principle, right? If the evidence for my belief changes, I should change my belief. Now, the problem, of course, with testing that experimentally is your beliefs are based upon all kinds of background, evidence, and information you've got. So testing it in an experimental situation is sometimes difficult, but this is what they did in an experiment, right? So what you do is you try and create a belief just in the experimental situation. So you're trying to create a new belief in the person, right in that experiment. And so the experiment is actually the place in which you're providing the evidence.

So what did they do is they brought a bunch of people in and they told them about this important skill that they wanted to see if they possessed, which is the ability to detect authentic suicide notes. Many of us have no experience with this. And so that's why it's plausible that this is going to be a situation in which a new belief is going to emerge. So the idea is I'm going to give you a bunch of notes. And you have to be able to tell me which ones are authentic and which ones are fraudulent. And this, of course, is a very valuable skill because it can help, you know, with first interveners, it can help prevent a real suicide. It can help us determine people who are just faking it or et cetera, et cetera.

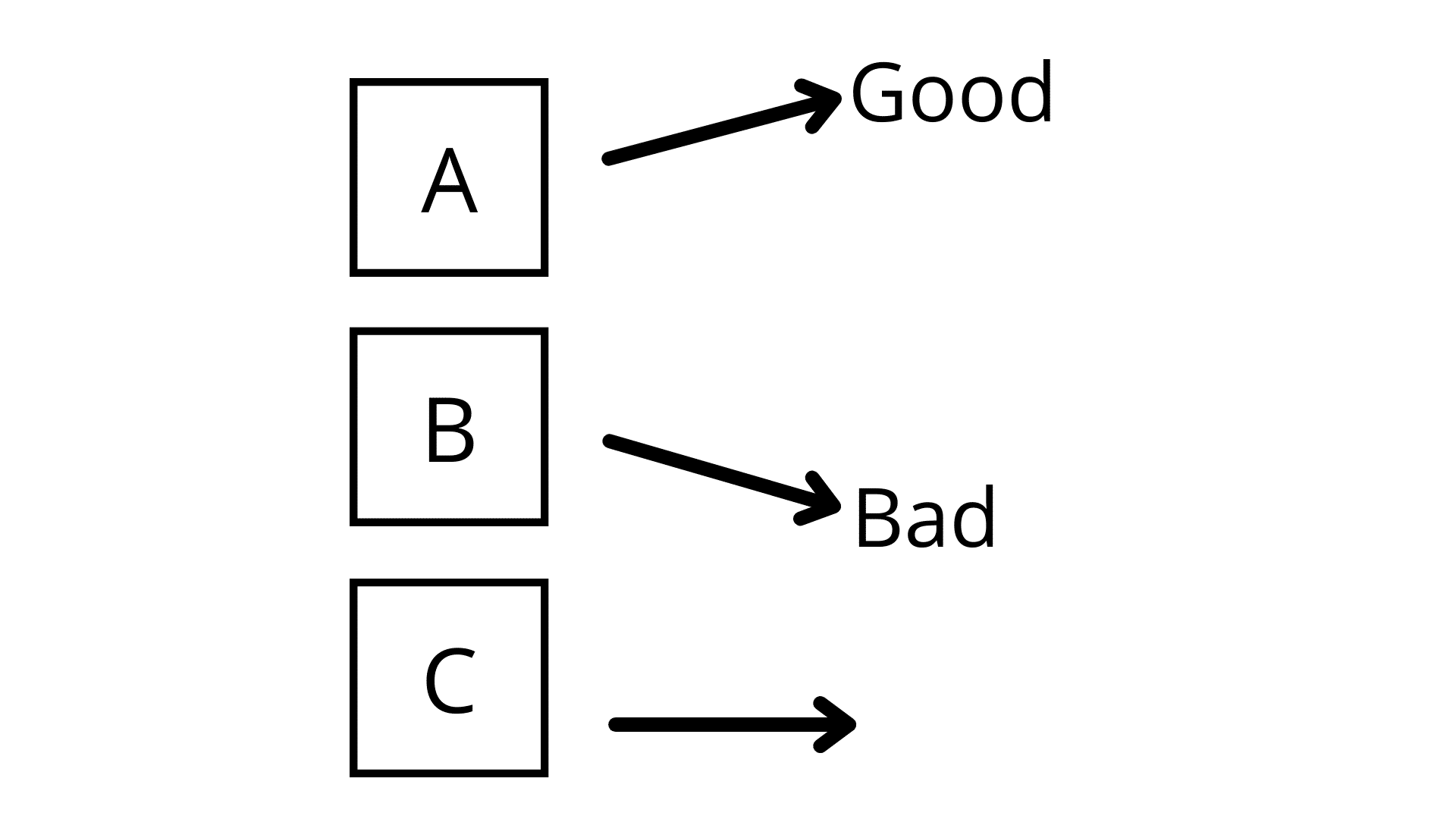

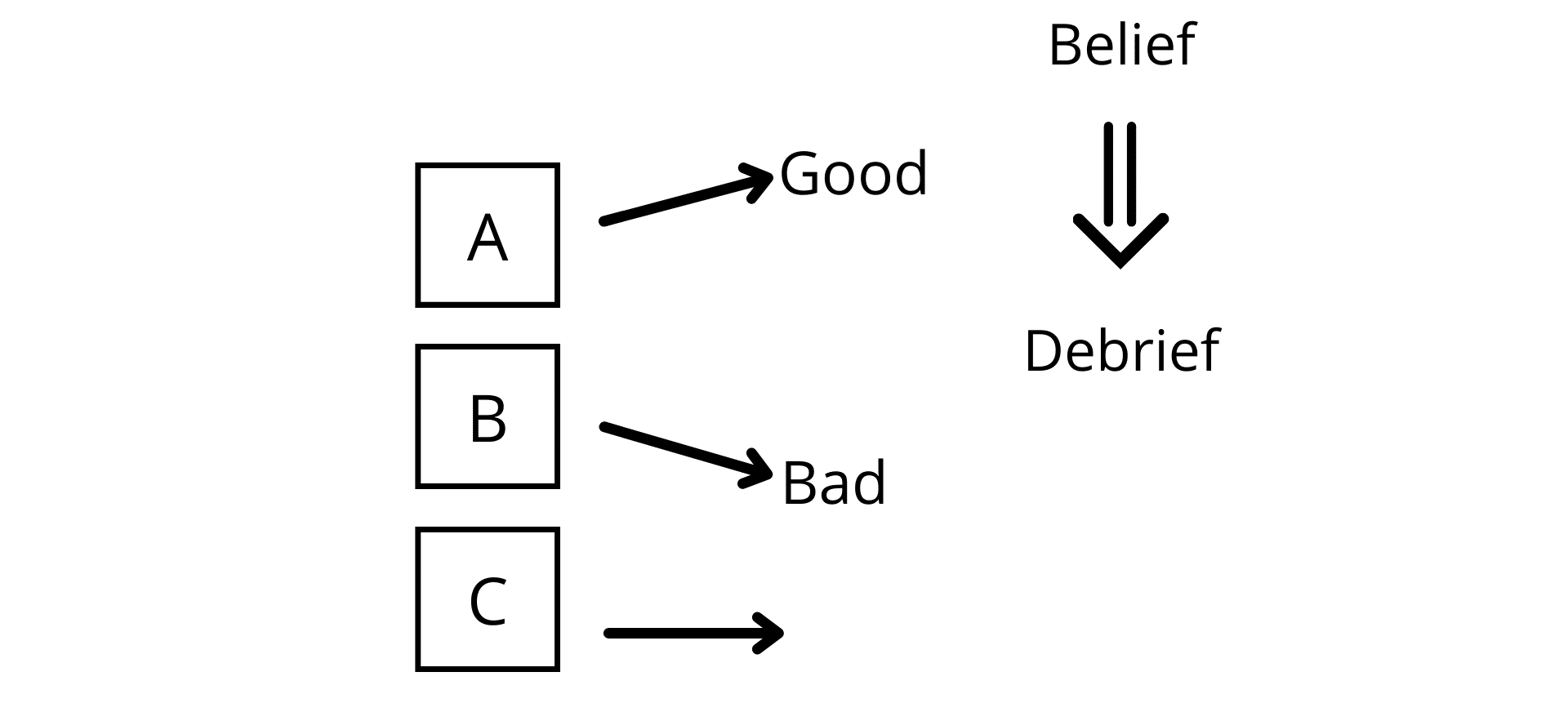

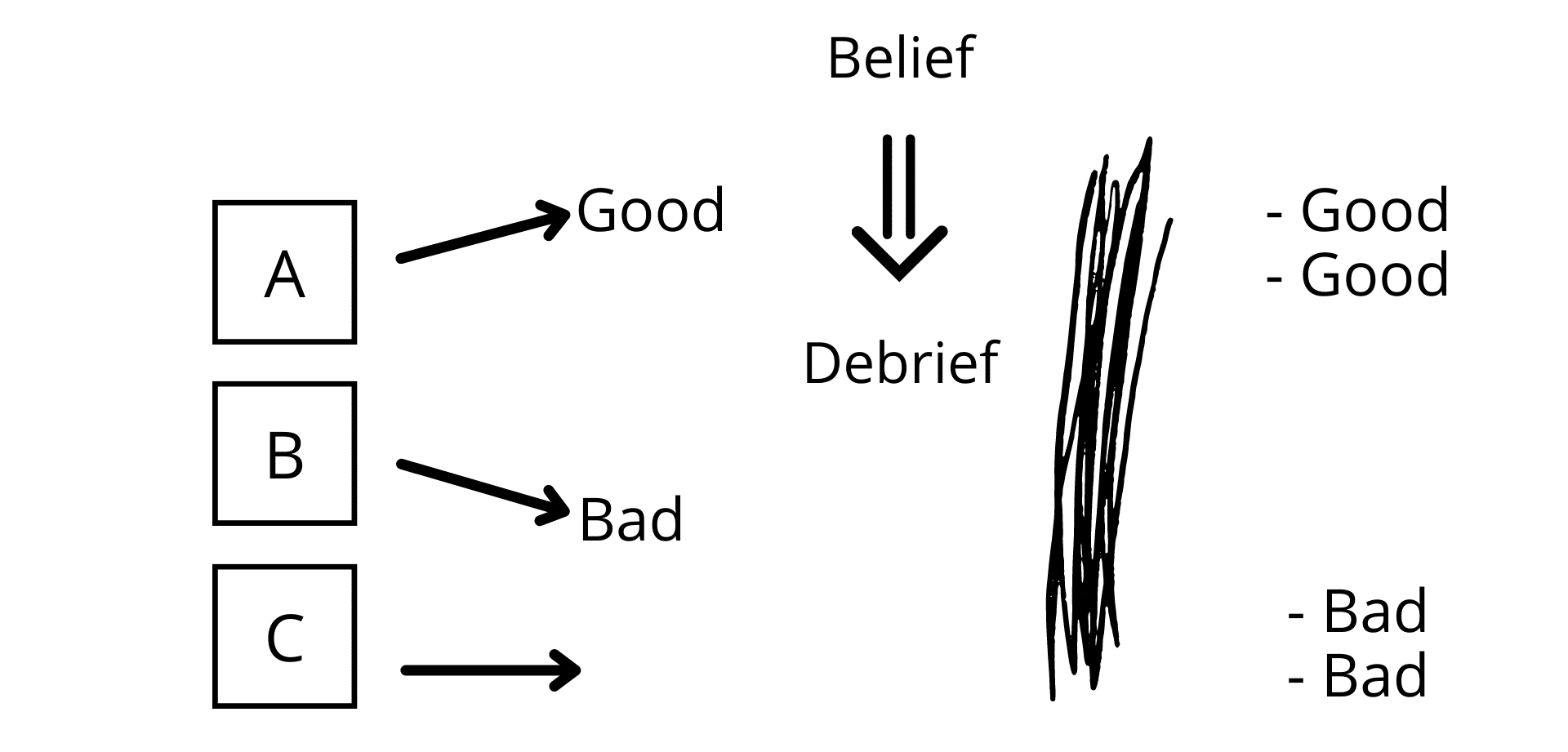

And so what you do is you give people a bunch of notes and they make their judgments. "I think this is real." "No, I think this is fraudulent." And then you, of course, give them feedback or, "Yes, that's, that's right." Or "That's incorrect." And then what happens is you later reveal to people, the following thing has happened. People were randomly assigned to group A, (Fig. 13a) (draws a square and writes A inside) randomly assigned to group B (draws a square below A and writes B inside). If they were in group A, they were told they were very good at this task. (draws an arrow from A and writes Good) If they were in group B, they were told they were very bad at this task. (draws an arrow from B and writes Bad) Of course, there's going to be a group C, (draws a square below C and writes C inside) which is the control group, and it's just going to be neutral and you're going to use them as a control. I'm not going to go into that because that's just good experimental design, right? And so these people (Group A) come to believe, again, on the basis of the evidence in the experiment that they're good. These people (Group B) come to believe they're bad.

Fig. 13a

Fig. 13a

And now this is what you now do. Once you get them to reliably evaluate like they self-evaluate. Say, "Yeah. I'm good. Look, I keep doing well on it." "No, no, I'm bad at this. I keep doing bad on [this]." Then you say, "Aha!" Then you debrief them, right (writes Debrief)? And you show them that they were only getting the feedback completely randomly. You show them two things. All of the notes are fakes. All of the notes are fakes. None of them are real. And you were given the feedback only on the arbitrary, on the arbitrary factor, the completely random factor that you were just assigned to group A, or group B. What that means, is the belief (writes Belief above Debrief) that you are good at this or bad at this should be completely undermined because the evidence for it: that these are real suicide—some of these are real suicide notes and that I'm getting the feedback based on my performance has been completely undermined. (Fig. 13b) (Draws an arrow from Belief to Debrief)

Fig. 13b

Fig. 13b

And now you give people a bunch of distractor tasks, so they're doing other things (Fig. 13c) (draws parallel lines), right? And then you come back and ask them, "Okay. But how do you think you would do on this in real life?" These people reliably report, "I'll be bad at it." (writes bad) "Oh, no," these people (points to Group A), "I'll be good at this." (writes Good) Or you ask them, "How would you do on a task very analogous to this? How would you be able to distinguish between fraudulent and legitimate marriage proposals?" Right? Something like that. And these people (indicates Group A) say, "Oh, I'll be really good at it." (writes Good) These people (Group B) say, "I'll be really bad at it." (writes -bad) This is known as belief perseverance. Belief perseverance, that people maintain the belief, even though the only evidence for it has been completely directly undermined in front of them.

Fig. 13c

Fig. 13c

So once again, what do we see here? People acquiesce on a principle. They say, "Yes, this is the principle,"—Notice my language. "I should use. I acknowledge and accept that I should use the principle that if the evidence is undermined, I should revise the belief." And yet they reliably do not do that. So again, and again, again, you have all these experiments and there is a lot of them. I've just given you three examples and there are like, there's like 15 kinds of experiments you can run and, you know, tens, sometimes hundreds of versions of these experiments. So people acknowledge the principle and then they reliably fail to engage in it. So they suffer—notice my language here—from systematic illusion, systematic self-deception.

Rationality Debate

All right. So a bunch of psychologists, cognitive scientists, and philosophers were coming to the conclusion that, well, that must— human beings are just irrational, right? They're just irrational. And so this idea that we've carried throughout all of our history from, you know, Aristotle on that human beings are the rational, the rational animals that's ultimately flawed. We're not. Human beings are not rational.

Now that's very problematic, right? Because think about what that means. If you were convinced that that was deeply correct, that human beings are not rational, then you'd have a very tough time justifying democracy because if human beings are reliably irrational, democracy is a very bad idea. You should, you should have the few people who are reliably rational and let them rule for example. I'm not saying this, I'm not advocating this. I'm trying to show you the consequences. You know, our legal system is also based on the idea that people are fundamentally reasonable, reliably rational, but if that's not the case, can we hold people responsible for their actions? I mean, the way they're connecting evidence to belief to action is seriously, you know, problematic.

Morality depends—and this is something that Kant famously argued for— morality depends on rationality. People can only be held moral if they can also be deemed rational, right? If you keep doing the right thing because of luck, right? Or because of coercion, we don't think you’re moral—we think—but if you do the right thing because you have reasoned it out and come to the conclusion that that is the right thing to do, right, then, of course, we do deem you moral.

So as you can imagine, right? A debate arose, and this is a very good thing for science, right? So you notice what's going on here with rationality. Rationality isn't just a fact out in the world, like whether or not the earth is round. Rationality ultimately goes, because it is so deeply tied to perspectival and participatory knowing it, goes deeply to who and what I am. And that has implications for what kind of political citizenship I can have. What kind of moral status I can have. What kind of legal status I can have, even your judgments for example, if I'm mature, immature are going to be vectored through how well you —how you assess how rational I am. Rationality is a deeply existential thing.

So a debate ensued around this, whether or not we should interpret the experiments are what they are, and they're robust and reliable, they are not suffering the replication crisis, these experiments. So these experiments are robust and reliable, but there's a debate about, and there's always and there always should be a debate in science about how you interpret your experiments. Should we interpret these experiments to mean that human beings are fundamentally irrational?

Now, a debate ensued. And that debate is very important. And I want to go through this debate. Why are we doing this? Well, first of all, I'm trying to show you the deep connections between wisdom and rationality. And I'm trying to show you the existential and political and moral import of rationality. And I'm also trying to get you to consider expanding and revising the notion of rationality in a way that will help us to come back and deepen our understanding of wisdom. Why are we trying to understand wisdom? Because wisdom is deeply associated with meaning and wisdom is deeply needed for addressing the project —sorry, for cultivating enlightening— for the project of enlightenment and addressing the perennial problems and also for the project of addressing the historical forces that have driven the meaning crisis.

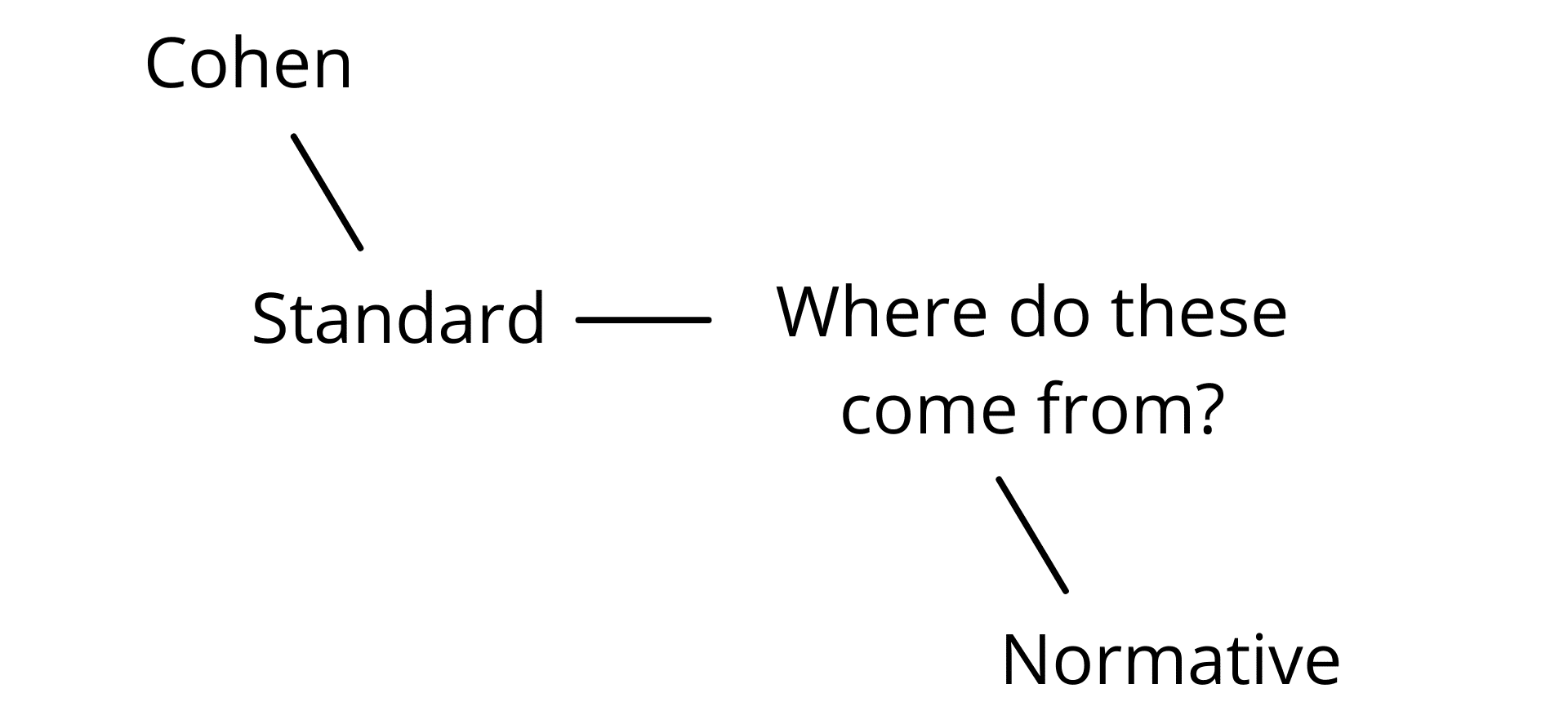

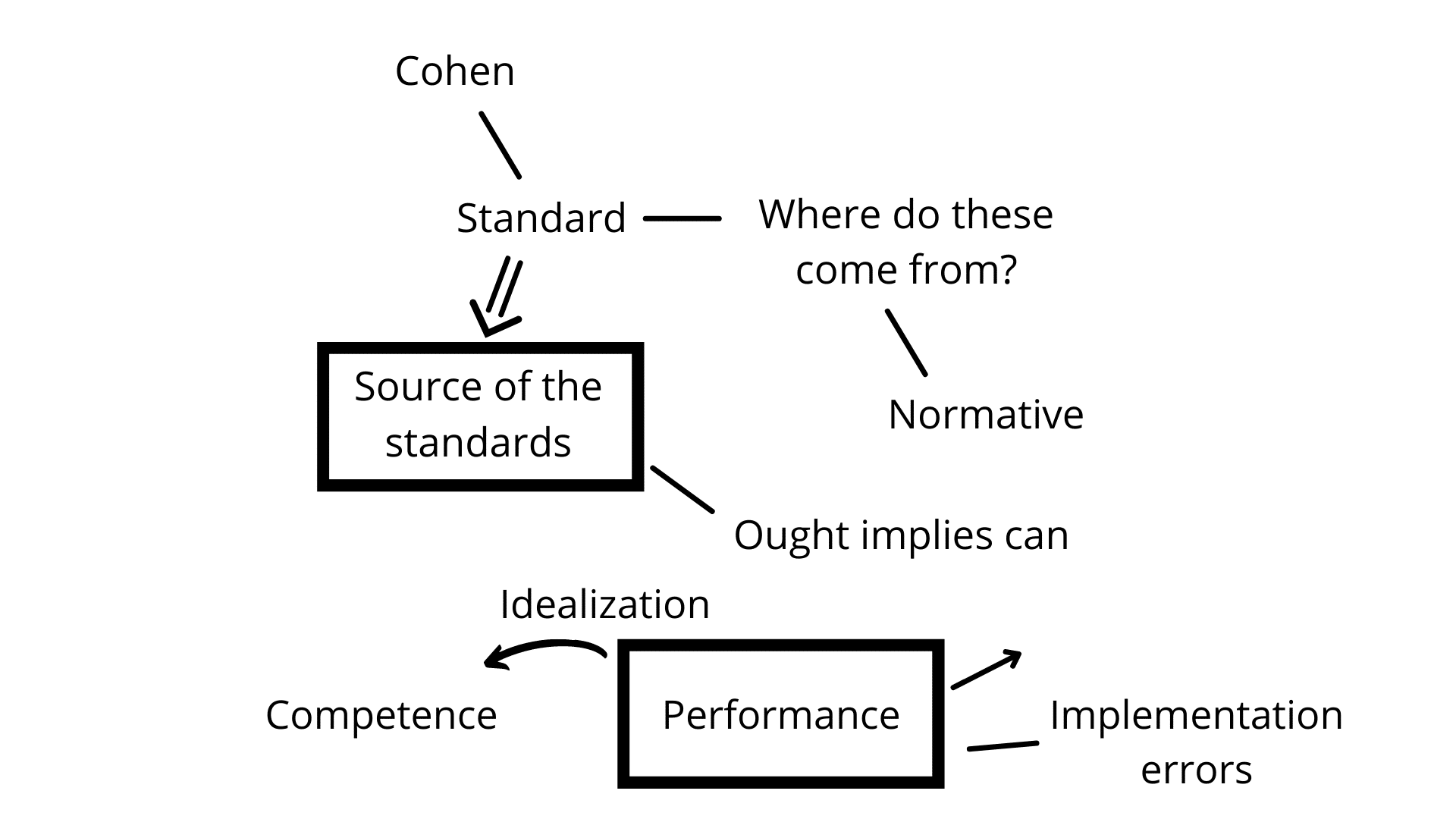

Okay. So the rationality debate, the first major response is by Cohen (writes Cohen). And Cohen makes a very important argument. It's an argument that we have—we need to go carefully through and see again, this is what I mean, there has been so much deep work put into the notion of rationality. We should not take the, right, self-proclaimed promoters of rationality on YouTube to be clear examples of what rationality is. Okay? We have to do this more carefully, cautiously, reflectively paying much more attention to the scientific evidence, the empirical evidence and the debate.

So Cohen argued that there is a problem with concluding that human beings are fundamentally irrational. And his argument comes down to a couple of very key points. So let me use this word cause... okay (writes Standard below Cohen). Cohen says, okay, to be rational is to acknowledge and to follow a set of standards. And we noted that, that we can only attribute irrationality to someone, something if it acknowledges the standards and then fails to meet them. To say that this book is irrational makes no sense because it does not acknowledge the authority of those standards. (Text overlay appears saying, The book as a physical object, not the statements in it) So the fact that it fails to meet those standards is no reason for calling it irrational. The book is arational.

Okay. So Cohen stops right there. And he says, well, let's slow down. Let's ask ourselves, where do we get these? (Fig. 14a) (writes Where do these come from?) The way he asked this is how do we come up with our normative theory? (writes Normative) Normative, not meaning statistically normal here, but normative meaning that the theory about the standards to which we should hold ourselves accountable when we're reasoning. So where does our normative theory come from, right?

Fig. 14a

Fig. 14a

Reason As The Source Of The Norms

And then he makes use of an argument that goes back to Plato and it goes all the way through to Kant. And it's like, well, there's a deep sense in which reason has to be autonomous. Let's say, I believed that my standards were given to me by some divine being, right, in the sense that it is commanded of me. There is some Moses of rationality. And then he comes back or she comes back with the commandments for how we're supposed to reason. So if we follow these just because we are commanded to do so, that is ultimately not a rational act. That is just to give into authority, to give into fear. And we would be doing the same thing regardless of what those standards were, right? If we follow the standards because we acknowledged that they're good and right, that means we already possessed the standards. This is an old argument that goes back to Plato. It's in the Euthyphro dialogue, right? Where normativity has to be really deeply autonomous if something is only good because the gods say it, then the gods aren't good in saying it. Look, if God says to you do "X" and " X" isn't independently good to do, then God saying do "X" does not make God good because it would only make God good to say doing "X" if doing X was independently good. And if we only do something because we're commanded to do it, not because we independently accept that it is the good or the right thing to do, then we are also acting arbitrarily and not acting in a good manner.

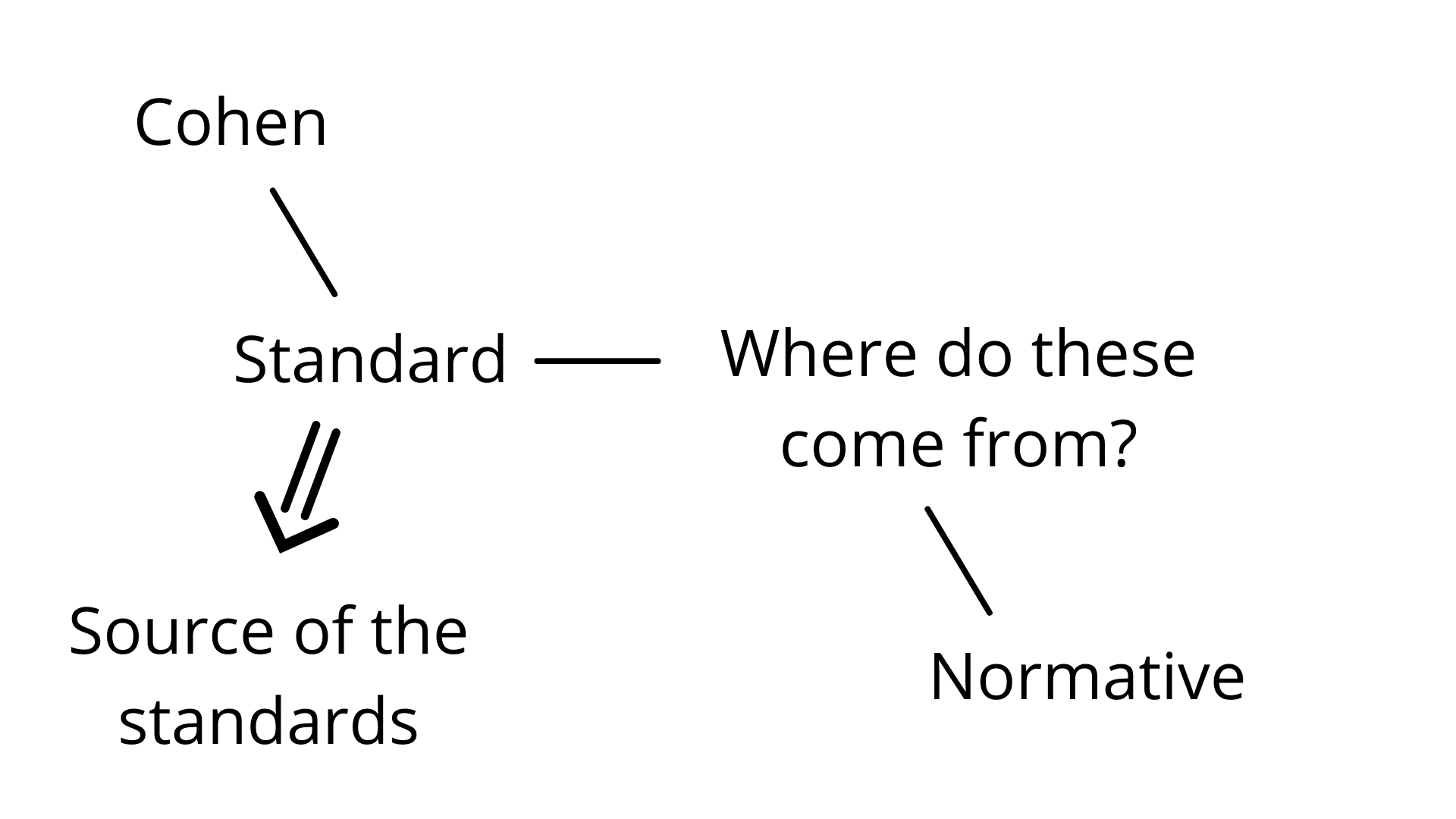

So we have to possess the standards. This is an argument that's crucial in Kant. Reason is ultimately autonomous. Not in the sense that people misunderstand it, that it's like a God or that it has absolute source. It's that reason has to be the source of the very norms that constitute and govern reason because that's how reason operates. Okay. So we have to be the standard.

Ought Implies Can

There's another way of seeing this. Ought implies Can. I'll give you two separate arguments for this idea. Ought implies Can. (Fig. 15) (writes Ought with an arrow pointing to Can) If I lay (underlines Ought) a standard upon you, "You ought to do this," then you have to be able to do it. It makes no sense to apply a standard to you that you do not have the competence to fulfill. Okay. "You ought to always say what is only certain and perfectly true. And if you don't, you are failing; you're immoral in some fashion." But that's of course impossible. You can't lay on anybody the obligation to speak all and only what is true. Because everybody has false beliefs. Most of our beliefs are false. And nobody can act comprehensively according to standards of certainty. If I lay that standard on you, it's a mistake because you don't have the competence to fulfill those standards.

Fig. 15

Fig. 15

Okay. So (erases Fig. 15), and there's just so much argument that converges on this point. (draws a downward arrow from ) Okay. We are the source of the standards. (Fig. 14b) (writes Source of the standards below Standard) That's of course, why you so radically acquiesce to them, but then of course you should immediately say, "Right. But what the experiments show is: yes, people acknowledge the standard, but they fail to satisfy them." Well, then Cohen does something very interesting. He says, well, we have to be careful. People make two kinds of mistakes, right? And what we have to do is we have to make a distinction between competence and performance.

Fig. 14b

Fig. 14b

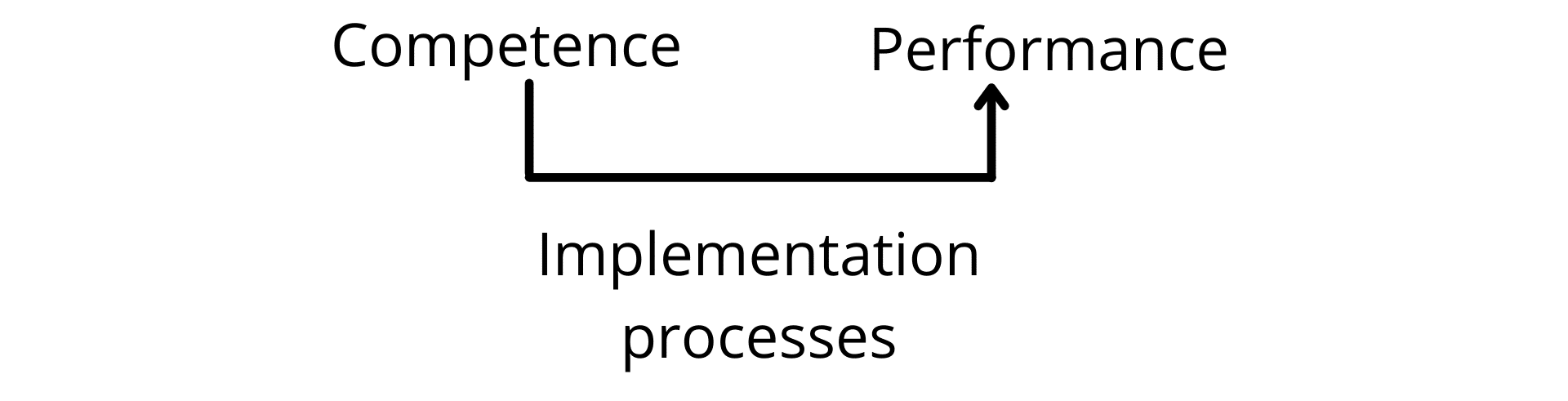

So let me give you an example. (writes Competence and Performance) This goes back to Chomsky and we talked about it when we talked about systematic error. Let's do it again, just to bring it back into the argument. Okay. Competence is what you're capable of doing; performances is what you've actually done. You have a competence that greatly exceeds what you've actually done. You have a competence to speak so many sentences that you will never speak, right? Right. So it is false that I have held my breath underwater for 17 days while listening to Beethoven's fifth symphony with a company of super-intelligent starfish. That sentence happens to be true by the way. The fact that I uttered it is bizarre. I probably would never have uttered it in my life. Right. So, but you have the comp—I have the competence to generate it and you have the competence to understand it. So competence is what you're capable of doing; performance is what you actually do.

Now, the thing is in between your competence and your performance, right? (Fig. 16) (draws an arrow from Competence to Performance) There are all the implementation processes. (writes Implementation processes below the arrow) You remember this? So I have the competence to speak English, but if I'm extremely tired, the implementation processes: the English in me doesn't—it comes up garbled. I start slurring my speech or right, perhaps if I was very drunk or something. Now you don't think that when I'm very drunk or very tired, that I've lost the competence. You just think, rightly by the way, that there's something interfering with the implementation processes, right? But if I get in a car accident and my brain is damaged and I am slurring my speech all the time, then you go, "Oh no, John's lost English." It's a different thing, right?

Fig. 16

Fig. 16

Process of Idealization

Now, Cohen does something really clever here. And he says, How do we come up with this? (encircles Source of the standards) Well, we have to be the source of it and it has to be something that we can hold ourselves to. Ought implies can. (Fig. 14c) (writes Ought implies can beside Source of the standards) Okay? So where do we come up with these standards? Well, what we do— this is how we come up with all of our normative theories. What we do is we look at our performance and we try to subtract (draws a diagonal arrow from Performance) from our performance. All of the errors that are due to implementation— implementation errors (writes Implementation errors beside Performance). Or as if they're often called performance errors, errors in how I'm implementing my competence. And so what I do is by this process of systematic idealization (draws an arrow from Performance to Competence and writes Idealization), I try to come up with an account of what my competence looks like completely free of performance errors. So what would I have to have in my head so that I could reliably speak and understand English all the time in a perfect manner? Now, of course, all the time I'm speaking, because of implementation processes, there are performance errors. I sometimes stammer, I sometimes stutter there's gaps. I speak elliptically. Notice there I just went, "I—I." Those are performance errors and you read through those, right?

Fig. 14c

Fig. 14c

So what we do is we take our performance. We put it through a process of idealization. We try and subtract all the performance errors that come from the implementation. And then we get a purified account (encloses Competence in a box) of our competence, an idealized account. But in that sense that it's purified of a distortion by performance errors. And then that is the standard to which we hold ourselves. That's how we come up with a normative theory that shows how we can be the source of it and how we're ultimately capable of it, but how we can nevertheless, a lot of the time fail to meet it (taps Performance). So what he argues, brilliantly, but we're going to see there's going to be problems with it. He argues that all of the errors in these experiments have to be performance errors (encircles Performance). That all of the mistakes that people are making are like the slips of tongue that pervade my speech; they're performance errors, because why? People have to be the source of the standards and they have to be able of meeting those standards. So we might just have at the level of our competence all of the rational standards, we must be, at the level of our competence, rational beings. And the only reason we're making those mistakes is performance errors, which means that human beings are not fundamentally irrational after all; they are rational.

Now, what I want to show you next time is what's right about that argument and what's deeply wrong about that argument. How Stanovich and the work of Stanovich and the rest reply to this argument (indicates Fig. 14c) in a really brilliant way and what it's going to show us again about the nature of human rationality. Human rationality is much more comprehensive than facility with syllogistic logic, right? It is the reliable and systematic overcoming of self-deception and that has to do with us, not just sort of theoretically. It has to do with us existentially and therefore this notion of rationality deeply overlaps with, and, I am going to argue, is a component of what it is to be a wise person; to be able to systematically see through self-deception and into reality in such a way that, like rationality with wisdom, we can actually afford meaning in life.

Thank you very much for your time and attention.

- END -

Episode 40 Notes:

To keep this site running, we are an Amazon Associate where we earn from qualifying purchases

Article Mentioned: On Defining Wisdom

Leo Ferraro

Publication: Relevance, Meaning and the Cognitive Science of Wisdom

Keith E. Stanovich

Keith E. Stanovich is Emeritus Professor of Applied Psychology and Human Development, University of Toronto and former Canada Research Chair of Applied Cognitive Science.

Publications by Keith Stanovich

John Kekes

John Kekes (/kɛks/; born 22 November 1936) is Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at the University at Albany, SUNY.

Book Mentioned: Moral Wisdom and Good Lives – Buy Here

Agnes Callard

Agnes Callard (born January 6, 1976) is associate professor of philosophy at the University of Chicago.

Book Mentioned: Aspiration: The Agency of Becoming – Buy Here

Conjunction fallacy

The conjunction fallacy is a formal fallacy that occurs when it is assumed that specific conditions are more probable than a single general one.

Confirmation bias

Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms or supports one's prior beliefs or values.

Wason selection task

The Wason selection task (or four-card problem) is a logic puzzle devised by Peter Cathcart Wason in 1966.

Rationality debate

The Rationality Debate—also called the Great Rationality Debate—is the question of whether humans are rational or not.

Cohen

Laurence Jonathan Cohen, FBA, usually cited as L. Jonathan Cohen, was a British philosopher.

Ought implies can

"Ought implies can" is an ethical formula ascribed to Immanuel Kant that claims an agent, if morally obliged to perform a certain action, must logically be able to perform it:

For if the moral law commands that we ought to be better human beings now, it inescapably follows that we must be capable of being better human beings.

The action to which the "ought" applies must indeed be possible under natural conditions.

Euthyphro dialogue

Euthyphro, by Plato, is a Socratic dialogue whose events occur in the weeks before the trial of Socrates, between Socrates and Euthyphro. The dialogue covers subjects such as the meaning of piety and justice. As is common with Plato's earliest dialogues, it ends in aporia.

Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky is an American linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist, historian, social critic, and political activist.

Other helpful resources about this episode:

Notes on Bevry

Additional Notes on Bevry