Ep. 44 - Awakening from the Meaning Crisis - Theories of Wisdom

(Sectioning and transcripts made by MeaningCrisis.co)

A Kind Donation

Transcript

Welcome back to Awakening from the Meaning Crisis.

So last time, we took a look at the theory of Schwartz and Sharpe. And that was an important theory for linking wisdom to virtue and positive psychology. And we saw the deep connections between wisdom and the cultivation and practice of virtue. We made some criticisms of Schwartz and Sharpe. I argued that they should include sophia and not just phronesis. If you remember those, they were invoking Aristotle's two notions of wisdom and giving priority to phronesis. I think you need both as Aristotle argued: sophia and phronesis in order to be virtuous. I also argued that their attempt to explain phronesis with expertise, I think it was confused and we should put that aside.

And then we took from that some ideas about the, you know, the developmental aspect that's, of course, central to Aristotle. Remember, he brought the developmental dimension to wisdom and how much wisdom is becoming the virtuous person. Other things I think are lacking in the theory—and we'll come back to this, that there wasn't much discussion about the connection between wisdom and meaning in life.

But we then passed to taking a look at a theory that took very seriously the connection between wisdom and virtue. And this is the seminal theory of work of Baltes and Staudinger. We took a look at the idea of the metaheuristics, pragmatics for orchestrating mind and virtue and excellence. And they talked about the fundamental pragmatics of life. I pointed out to you that a way of making sense, conjointly of the invocation of metaheuristics and both senses of pragmatics is this idea that its core to wisdom is this capacity for relevance realization, obviously improved in some fundamental way, which I think means that there is integral connections between wisdom and intelligence via the notion of rationality that we've already been developing together.

And then we took a look at the five criteria where there was clear indications of propositional knowledge, procedural knowledge. The contextualism, I argued can be best, be seen as perspectival knowing. I argued against their notion of relativism and argued instead for humility and fallibilism. And then, obviously, I have the—I think that's—I'm sorry that was maybe too harsh to them. I think it's pretty clear that many of the seminal figures of wisdom figures from the past were not moral relativist or relativist in any significant way. So we—I strongly recommend replacing relativism with fallibilism and humility.

And then finally the fifth criteria is that wisdom is applicable to domains in which there is uncertainty. And of course, as I've already argued that a huge aspect of our life and our cognition, because ill-definedness, combinatorial explosion, et cetera, et cetera, which again means relevance realization is being strongly presupposed.

I want to give you some further quotes to indicate what's going on about that. So they talk about a wisdom having to do with generativity, flexibility and efficiency in application. And of course the, the generativity and, but the flexibility, but also the efficiency are bringing together many of the ideas that we've been talking about with relevance realization. They talk about it taking place—listen to this language—within the frame of bounded rationality. They're invoking the notion here from Simon. Bounded rationality. This is rationality that is taking place within a framing, you know, it's taking place within the constraints of a combinatorial explosion, within the constraints of working with ill-definedness. It's a notion of rationality deeply enmeshed with relevance realization.

They talk about a highly comp—these are all quotes. I'm giving you, by the way—highly complex sets of information about the meaning and conduct of life are—highly complex, okay?—are reduced quickly—listen to this!—to their essentials without being lost in the never ending process of information search—notice that combinatorial explosion directly being invoked here—that were to occur if wisdom was treated as a case of unbounded rationality. So I think it's pretty clear from all of those quotes that they are directly invoking the machinery of relevance realization.

I pointed out that they—with their criteria, they were able to begin the operationalization of wisdom and in some of the first experimental work, they found that cognitive style in which one had excellent skills of judgment, seemed to be predictive of the ability to do well in the experiments. They also found that discussing with another person or imagining discussing with another person enhance your capacity for wisdom, challenging an individualistic notion of rationality going back to Descartes and assumed, if you remember, by Cohen in his arguments. But what's really interesting about that is, you know, of course, this brings up the relevance of platonic dialogue, but also the Stoic idea of internalizing the sage because the case where people imagined talking to the significant other was just as efficacious as actually talking to a significant other. And both of those were more efficacious than just giving more time to think and reflect on your own.

I pointed out that one plausible explanation for why this works is that you're getting something like what Igor Grossman has shown with the Solomon effect that the move to take the perspective of other people—move to a third person perspective really enhances... I'm sorry, I'm going to have to get a drink. I seem to have something caught in my throat. Really enhances one's ability to overcome the transparency and the bias induction of one's own perspective and that it can be facilitated, of course, if you not only are taking the perspective of somebody who's present, but you can do that by simulating them internally. And eventually you could internalize that perspective the way we've talked about with the Stoics, internalizing Socrates, and one can learn to—remember this?—one can learn to converse with oneself dialogue, with oneself, do something like, and link us with oneself and provoke aporia, provoke the challenge and the demand for transformative change.

I think all of this is really excellent work on their part. I noted that they also, like Schwartz and Sharpe, I think, make the mistake of trying to understand wisdom in terms of expertise. And I'm not gonna repeat that argument. And I think that it is a kind of fundamental mistake. I think, understanding wisdom on the lines of something like rationality is a much more fruitful connection.

Further Criticism Of Baltes And Staudinger

Now, what are some further criticisms of Baltes and Staudinger? I think one of the most important criticisms I would make, other than the ones I've made about expertise and not being very clear on explicating the role of perspectival knowing—that's kind of an unfair criticism, cause it's anachronistic, but we should at least endeavor to bring that into our account of wisdom, given their own experiment and given the further work of Igor Grossman.

I would also say that one of my criticisms, and this is a criticism that I made with Leo Ferraro and the 2013 article we published on wisdom. I would argue that there's a mistake here at a more theoretical and conceptual level. It's a mistake of omission, not commission. What we're getting here is a product theory of wisdom (writes Product theory of wisdom) in which what you're trying to do is to come up with sort of the account of what wisdom is, and that's a valuable thing you should definitely do that you should try and come up with, not just a feature list, of course, that's a little bit of a problem with just the list of criteria, of course, but what you do is you want to come up with, you know, what am I going to do? I'm going to find wise people. I'm going to get, sort of, you know, widely shared definitions of wisdom and try and come up with an account of what wisdom is based on that. And that's a legitimate thing to do. It omits something that's very important though. It omits what we saw as so central to the ancient theories of wisdom that we were looking at. If you look at Plato, even Socrates and Plato and Aristotle and the Stoics, and if you look at the Buddha, and the centrality of transformational change in wisdom is being lost in a product theory. What you also need (Fig. 1a) (draws a double headed arrow beside Product theory of wisdom)—and these two should talk to each other—you need a process theory. You need a theory.

Fig. 1a

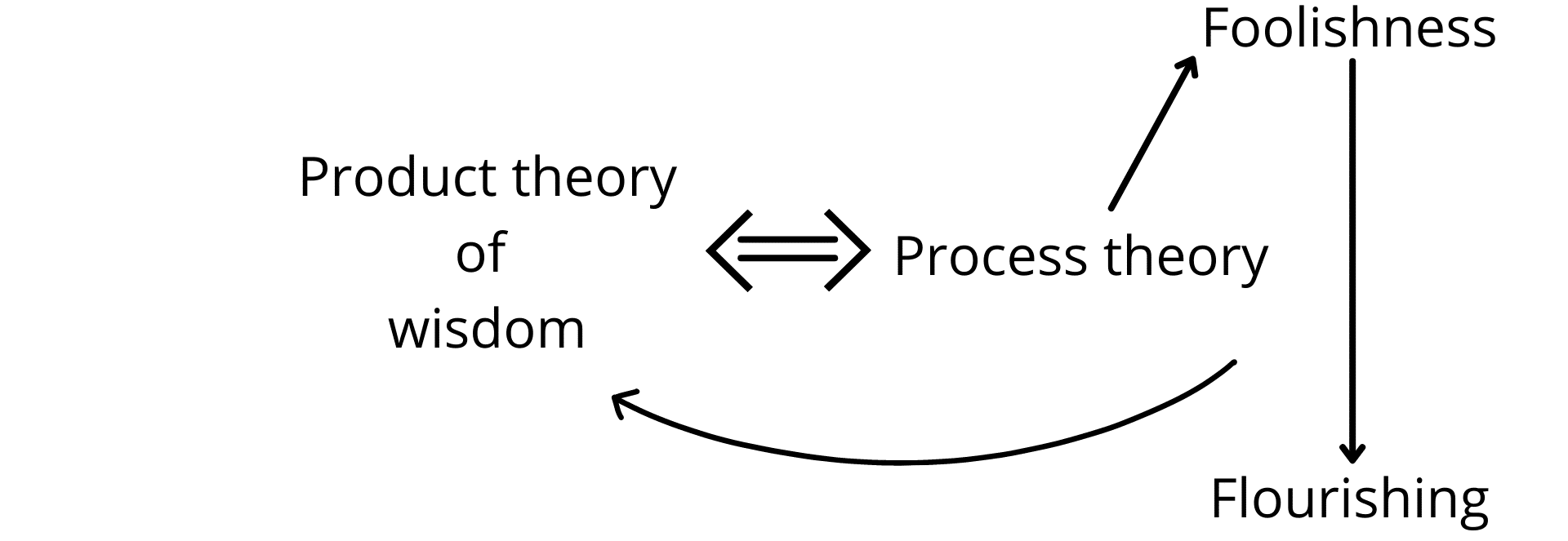

And this is what I think the ancient theories of wisdom are. You basically—what you're getting is (taps Process theory) an account that works something like this in a process theory. You have an independent account of what is foolishness (Fig. 1b) (writes Foolishness) and what is flourishing (writes Flourishing below Foolishness). And then what a process theory tells me is how I can overcome foolishness (draws an arrow pointing from Process theory to Foolishness) and how I can afford (draws arrow from Foolishness to Flourishing) flourishing. And then from that (draws an arrow from the arrow between Foolishness and Flourishing to Product theory of Wisdom), it tries to derive what wisdom is.

Fig. 1b

And I think this is a very important thing to do, to try and figure out what wisdom is from an account of how one becomes wise, because first of all, it taps into this longstanding and important philosophical heritage so there's a tremendous legacy that we've explored in this course that we should be making use of.

And secondly, it does something that I think is much clearer than what a product theory does, which is it picks up on the central insight that McKee and Barber talked about, which is seeing through illusion and into reality. The process theory gives you an account of what self-deception is and how you can see through it and into reality so that you can be better connected to yourself, to other people, to the world and thereby flourish.

So I would advocate that in addition, not in competition, but complimentary to a product theory, we should be developing a process theory. Tells us what foolishness is, how foolishness develops, how we can overcome foolishness, how we can afford flourishing. And then on the basis of that, get into a dialogue with accounts of what wisdom is. So I think that's important. I think, I mean, the fact that Aristotle's being invoked really says we need to bring in the developmental and transformative aspects of wisdom (underlines Process theory) in a more serious manner. So that's one of my most central criticisms of Baltes and Staudinger. The other one, like I said, is they seem to make a mistake around expertise.

I would now like to share with you some central criticisms made by a really seminal thinker. Somebody I've had the chance to meet a couple times and interact with. And this is Monika Ardelt (writes Monika Ardelt 2004). I think she did something really important, which is the critique she published of Baltes and Staudinger in 2004 and her ongoing work she's generated one of the wisdom scales that is used experimentally. She's generated a lot of experimental work. Monika's work is really important and central.

Modal Confusion

Now, I'm going to use some of my language that we've developed in this course to talk about Monika and I hope it's not imposing on her, but I think it's plausible that it's not. Her main criticism of the Baltes and Staudinger paradigm or approach is they confuse—this is her criticism. And I agree with it. They're confusing having theoretical knowledge about wisdom with being a wise person.

So there's a sense in which there's a bit of a modal confusion going on in the Baltes and Staudinger theory. It's like, I have a lot of knowledge about wisdom, that doesn't make me wise. So I'm an excellent case in point of that, I would think, I mean, I've read a lot of the wisdom literature, about the philosophical, and the psychological, I teach on it. I, you know, I'm involved with this currently some experimental work, et cetera. So I think I have quite a bit of theoretical knowledge about wisdom. I would not in any way dare to equate that with the claim that I'm a wise person. While that knowledge, I think, could be argued to be necessary. I think what Ardelt is clearly pointing to is that it's nowhere near sufficient. It's nowhere near sufficient.

And so what, I think, she's pointing to is the fact that a wise person—and we can think of the Socratic example here about the truth and the transformative relevance needing to be kept together. The wise person must realize these theoretical truths within a process of self- transformation, must realize this within a process of self-transformation. So people that are wise have gone through a process of self-transformation. They have achieved a significant kind of self-transcendence that allows them to embody and enact these truths rather than just having them in a propositional fashion.

So, Ardelt is clearly pointing towards something missing (indicates Process theory): the importance of the process of development. She's also importantly pointing to the way in which wisdom is a project of, you know, becoming a particular kind of person. And so she—a particular kind of person living in a particular kind of world. And so she's directly pointing towards what I've articulated in this course as participatory knowing.

Distinction Between Descriptive Knowledge And Interpretive Knowledge

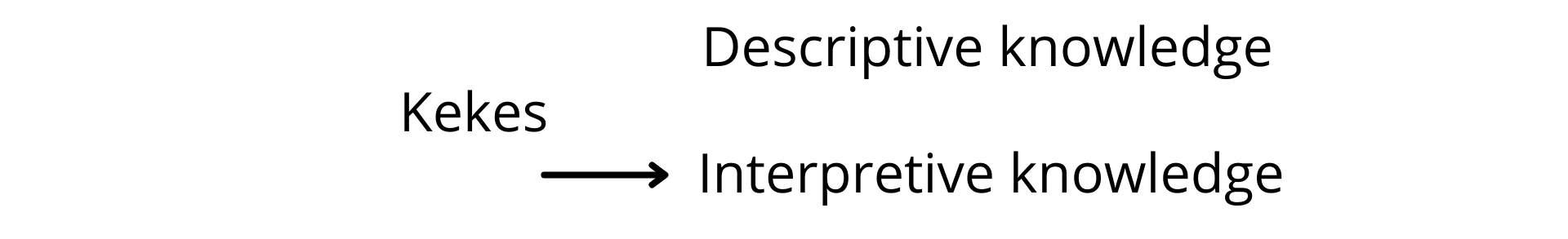

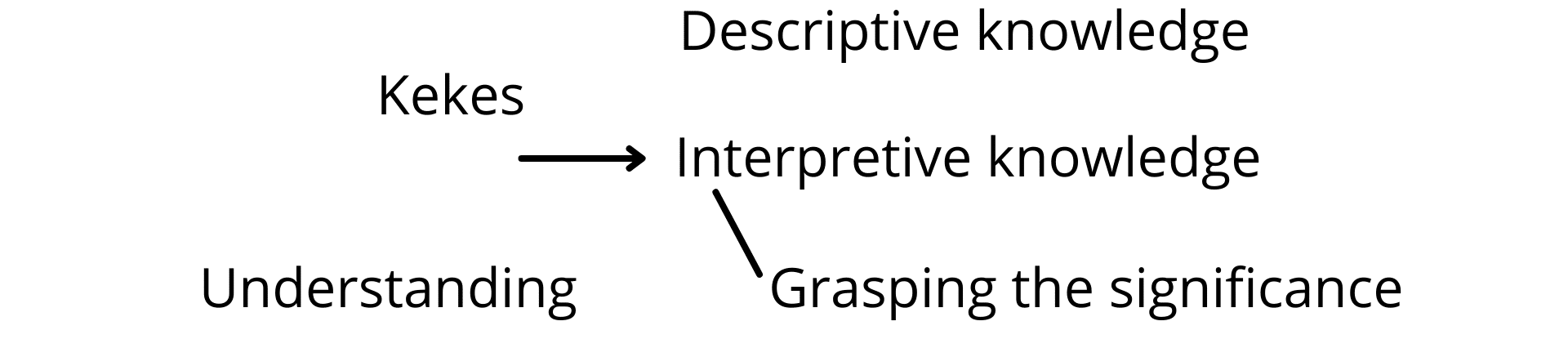

So she then brings out something very important about this distinction. She makes use of this distinction between having knowledge and being wise. And she makes use of a distinction from a really important philosopher, John Kekes (writes Kekes). I've mentioned him before that [he has] done some important work on moral wisdom and its relationship to virtue. And Kekes makes a very important distinction between descriptive knowledge (Fig. 2a) (writes Descriptive knowledge beside Kekes) and interpretive knowledge (writes Interpretive knowledge below Descriptive knowledge), which Monica points to.

Fig. 2a

And what Ardelt is pointing to is, of course, that wisdom has to do more with this (draws an arrow indicating Interpretive knowledge). So descriptive knowledge is basically your knowledge that, you know, the cat is a mammal. Your knowledge that the cat is a predator or something like that. Interpretive knowledge is your ability to grasp the significance of your descriptive knowledge (Fig. 2b) (writes Grasping the significance).

Fig. 2b

Now that's going to be important because that actually turns out to be a central feature in most of the theories that are now being developed about what understanding is and how it differs from knowledge. And I think what Ardelt is pointing to here by invoking Keke's notion of interpretive knowledge is the centrality of understanding (writes Understanding) to wisdom. And, of course, grasping the significance is putting us—I'm going to argue later, that this (encircles Grasping) of course is going to be, have to do with construal. And this (encircles Significance) is going to have to do about, of course, with relevance. Relevance realization.

Now, I think that's very important work and I think the fact that—there's so much happening in these theories and the thing is it's happening in a very sort of concise fashion. So let's gather what we've got here. We've got the realization that we shouldn't be just talking about having knowledge about wisdom (indicates Monika Ardelt 2004), we should be going through the process of self-transcendence (indicates Fig. 1) by which we become wise. That involves, as I said, a process theory. We're going to need a process theory, not just a product theory and that what the wise person has above and beyond knowledge (indicates Descriptive knowledge), I would call descriptive knowledge, knowledge, and Interpretive knowledge, whether that's knowledge, I don't know, but that's at least what many people are considering understanding. And this has to do, as I'm going to argue that—I'm going to argue that grasping the significance of your knowledge is, you know, good construal that realizes what's relevant.

Personality Characteristics Of A Wise Person

So Ardelt then talks about the personality characteristics that you should see in the wise person. So she thinks that if we want to talk about what it is to be a wise person, we shouldn't just be talking about the knowledge. Obviously. We should be talking about the kind of characteristics that the wise person has and that's important because we've already seen the deep connections between wisdom and virtue.

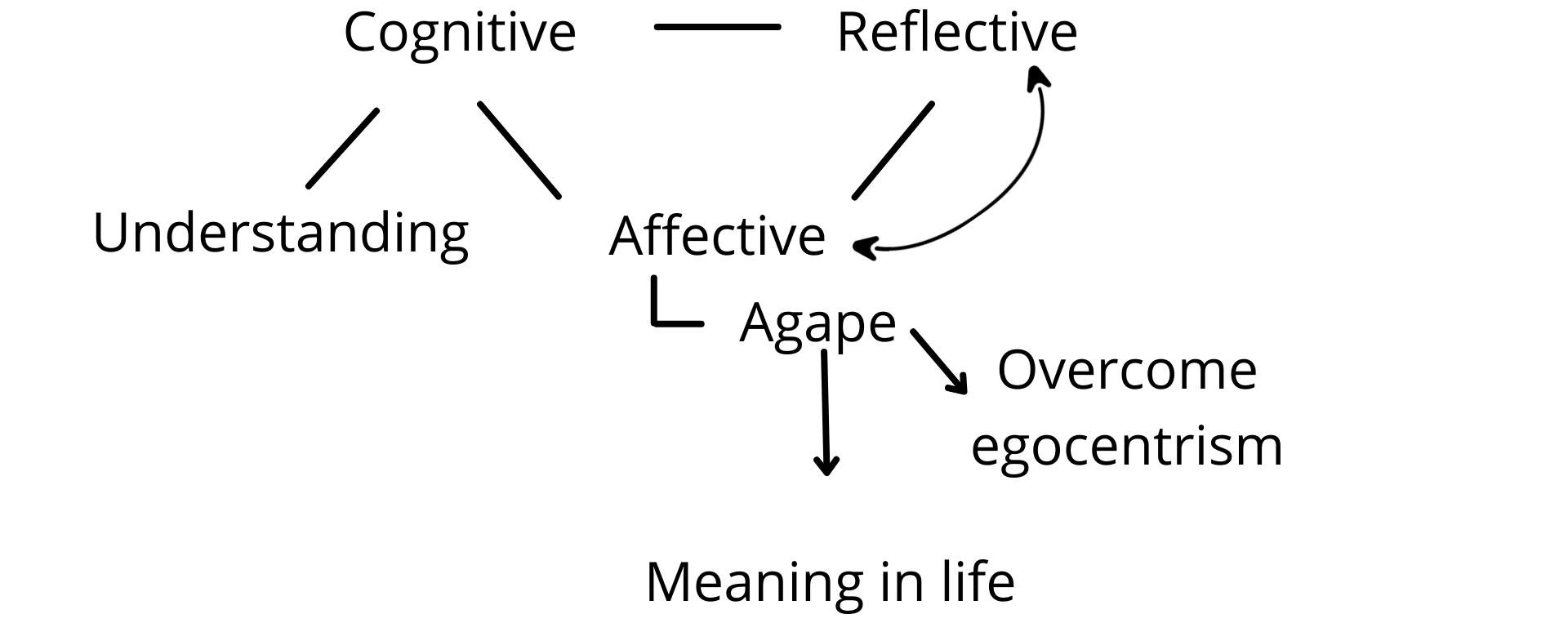

So she thinks that there are three ways in which we can judge the relative value. We can grasp the significance of info—of our knowledge. There's three domains—no, that's not right. I don't want to say domain. There's three dimensions of our personhood that are crucial for being a wise person (erases the board). She thinks there, and up until now, we've been clearly giving these emphasis.

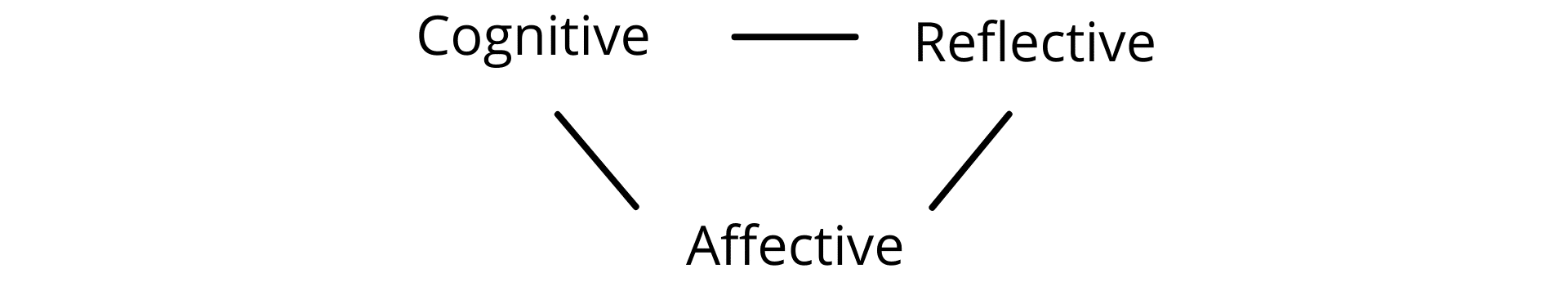

There are cognitive factors (writes Cognitive). So what are the cognitive factors here? This, of course, is your ability to gr—to have a comprehension of the significance and meaning of information. And not just theoretically. The significance of the information for your development, for your going through a process of self-transcendence and becoming a wise person.

Then there are reflective (Fig. 3a) (writes Reflective beside Cognitive). And I think the distinction here, this is picking up a bit on the way rationality has this reflective component into it, as opposed to intelligence, which is just your ability to grasp what's relevant. So I think that's something that can be integrated quite well with the discussion we had on rationality. So the reflective factors a person who has been cultivating wisdom is multi-perspectival. They're capable—excuse me, I don't know what's wrong with my throat. They're capable of engaging in multiple perspectives. They're capable of self-examination, self-awareness, self-insight. So notice again that the reflection here has an existential import. You're taking these perspectives, but you can ultimately internalize this perspectival ability onto yourself in self-reflection, self-examination, self-insight. So I think that's very valuable (draws a line connecting Cognitive and Reflective).

Fig. 3a

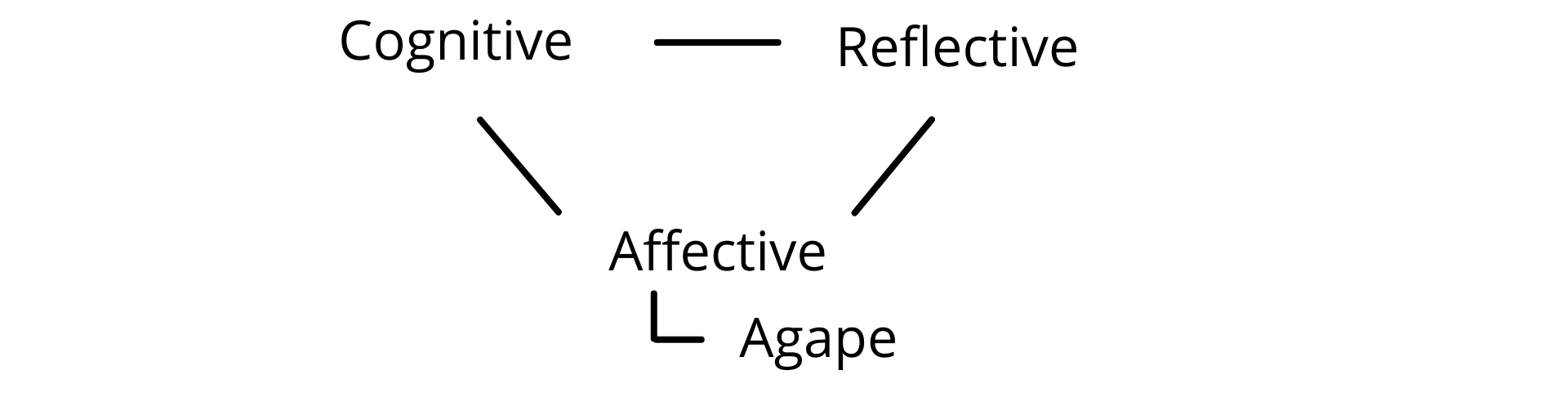

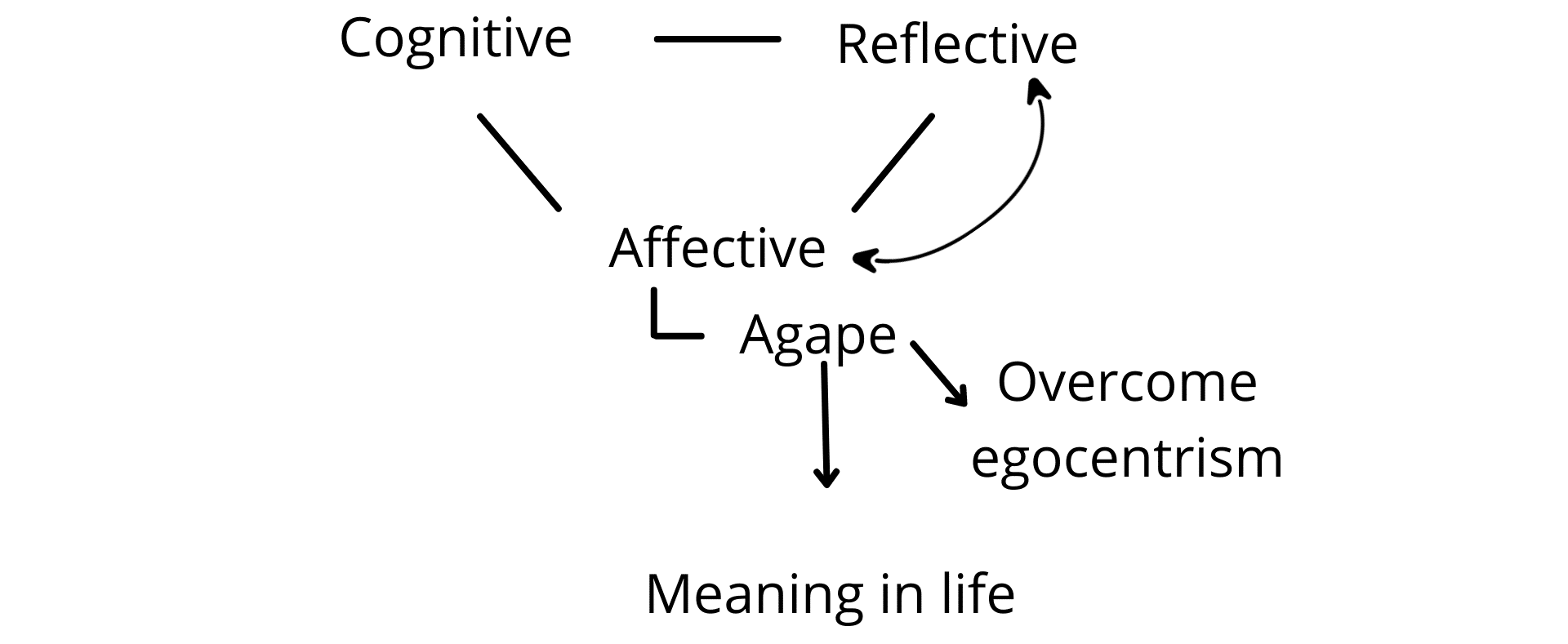

And then there's an affective component (writes Affective below Cognitive and Reflective). And I'm doing this because Ardelt clearly thinks that these three are mutually influencing, mutually constraining, causally interacting with each other. So the affective dimension, she talks about in terms of compassion, I've made a case that, so—because of some of the models she invokes from Buddhism, I don't think this is inappropriate. I've made a case that the capacity for agape (Fig. 3b) (writes Agape below Affective) is the best way of understanding compassion.

Fig. 3b

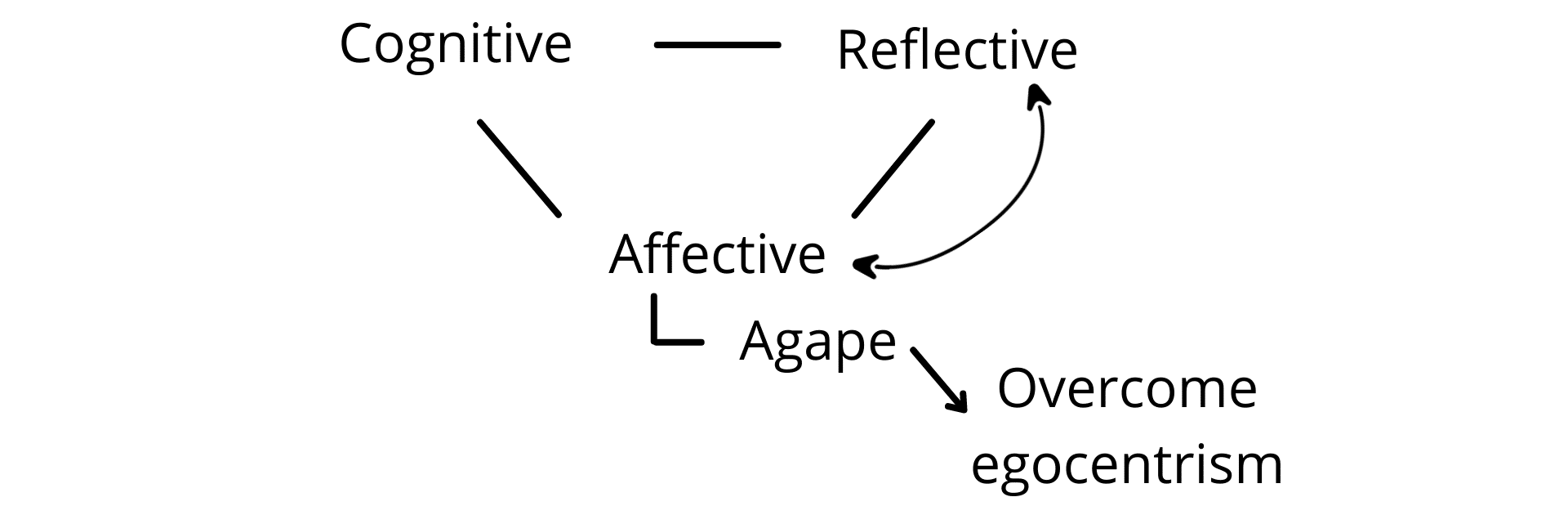

The main idea here is, and this is why I'm invoking agape, as opposed to either philia or eros is because it helps to overcome egocentrism and you can see how these two are working together (draws a double-headed arrow pointing to Agape and Reflective), right? How this (indicates Agape) is helping to overcome egocentrism (Fig. 3c) (writes Overcome egocentrism below Agape) in kind of a powerful way. So this is sort of overcoming egocentrism (indicates Reflective) perspectivally. And this (indicates Affective) is overcoming egocentrism attitudinally in terms of your core motivations, your core set of priorities and preferences. Basically the way in which you're caring about the world and that you're caring is directed towards the flourishing of other persons.

Fig. 3c

So I think that also is an important improvement in the theorizing. The fact that Ardelt is clearly giving equal priority to cognitive, I would call, you know, these are perspectival (indicates Reflective) and the perspectival aspects of rationality and, of course, the important affective things. And if you remember, this does something also, at least implicitly that we don't have in Baltes and Staudinger.

And so this is one other criticism I would make on behalf of Monika Ardelt of the Baltes and Staudinger theory, which is agape starts to (draws an arrow down from Agape)—I've argued, so I'm not attributing this argument to Ardelt but I'm supplementing it to her theory because what agape gives is, it at least gives a way of trying to talk about meaning in life (Fig. 3d) (writes Meaning in life below Agape), the way Wolf talked about it. And I argued that agape helps us to get that kind of connectedness and caring that is so central to grounding meaning in life. We don't have to ground meaning in life, in being subjectively attracted to something that's completely objectively attractive. We just have to be transjectively coupled to those things we find inherently valuable because of their connection to meaning making coherence and caring.

Fig. 3d

And so this (indicates Agape and Meaning in life) allows, well, what it affords and I would argue enables Ardelt's theory to do is to connect her account of wisdom to meaning in life in a much more direct fashion. That connection to meaning in life is not clear in Baltes and Staudinger.

And if you remember Wolf argues that you can't reduce meaning in life to morality. So the connection between wisdom and virtue while central, and being discussed well by Schwartz and Sharpe, and by Baltes and Staudinger, is not reducible to, it's not sufficient for the connection between wisdom and meaning in life. By bringing in this affective component, and the idea that we are becoming wise, not just thinking about wisdom, and so the process of identification, the modal existential aspects, Ardelt is doing a lot more with, about connecting wisdom to meaning in life. And I think that's very, very important.

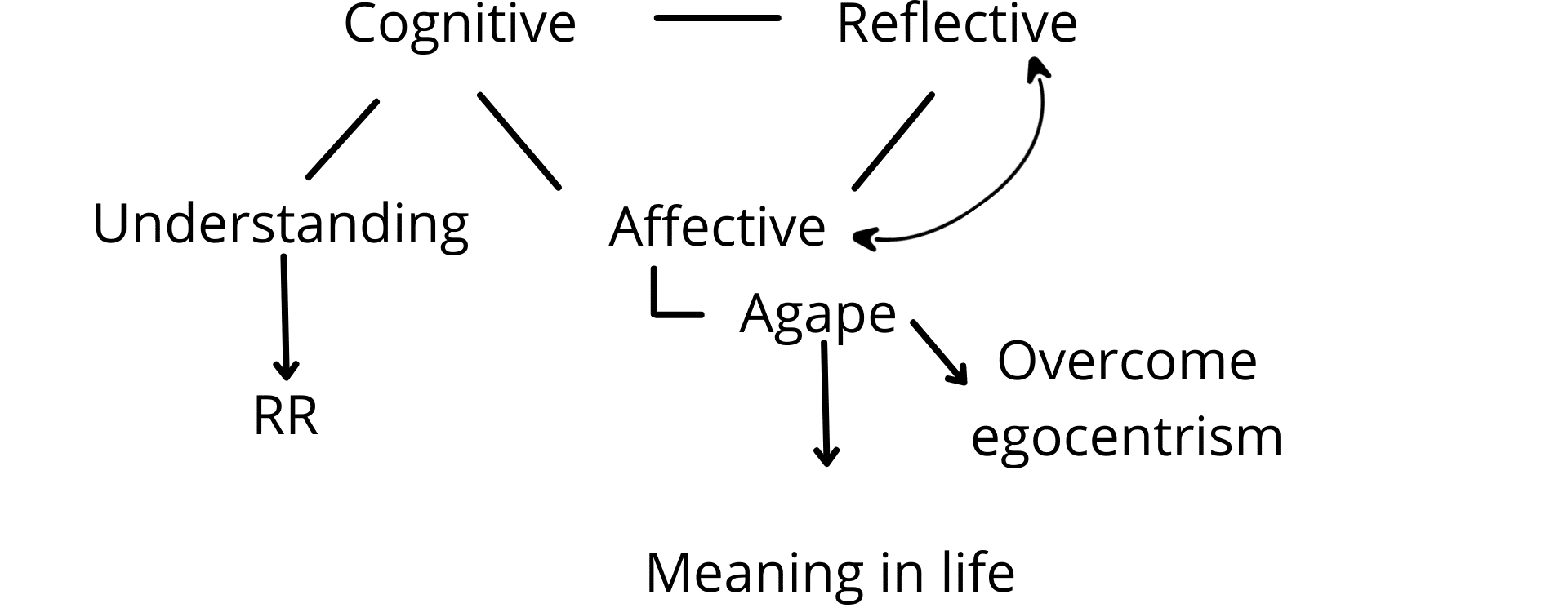

Okay. So, you know, this is sort of understanding (Fig. 3e) (writes Understanding below Cognitive) in a sense I'm going to help develop later. This ability to pick up on what to realize the significance of your knowledge. And allow you, and again, in an existential fashion, not just abstract, theoretical, but in a way that allows you to, I would argue, ultimately see through illusion and into reality so that you can afford your development.

Fig. 3e

Then you—that is connected to your reflective capacity, your perspectival knowing which ultimately could be linked to the stuff we saw with Grossman's work and in the Berlin paradigm of Baltes and Staudinger. The ability to take the perspective of others, being multiple perspectival and ultimately turn that back on oneself, in self-examination, internalize it in self-insight. And that those two (indicates Cognitive and Reflective) are also linked to something like a capacity for agape. And I would argue that you need these two (indicates Agape and Reflective) for overcoming egocentrism and it also—I haven't seen Monica develop this very explicitly in connection, especially with Wolf's work, but there's the real potential here of connecting wisdom to something other than virtue. It should be connected to virtue, but it should also be importantly connected to meaning life.

What are some of my criticisms of Ardelt's work? Well, it clearly invokes transformational processes. It doesn't really incorporate a theory of transformative experience or an account of it. You know, like we have in LA Paul's work. It doesn't really give us a processing theory. It points towards the—and this is important—it points towards the need for a processing theory, but it doesn't give us an account of what that process looks very much like.

And it doesn't have an independent account of foolishness. It doesn't really tell us very much what foolishness is and that's something needed if we're going to, I would argue, to have a good process theory of wisdom. There is an untapped potential. This isn't so much a criticism as encouragement that there's an untapped potential, given this theoretical machinery of connecting wisdom to meaning in life in a way that compliments the connections between wisdom and virtue.

So I think these are all some very important features about this. I've already indicated, you know, grasping the significance. I think this is points towards RR (Fig. 3f) (writes RR below Understanding). We've already talked a lot about agape and the relationships I tried to drive between it and relevance realization. And, of course, I've already indicated this (indicates Reflective) is bringing in the recursive aspects. It's bringing a perspectival knowing. And there's also, at least in the background sense, the participatory knowing because one is coming to know oneself differently. One is coming to know the world differently, because one is going through this inherent transformational process.

Fig. 3f

So (erases the board) we're seeing how the theory of wisdom is sort of building up. It's becoming more complex. It's bringing in different aspects of, you know, the different kinds of knowing, there is, you know, quite important aspects of relevance realization in Schwartz and Sharpe clearly in Baltes and Staudinger. Quite strongly implied in the central role, at least in the cognitive aspects—although I would argue also in the reflective and the affective aspects of Ardelt's theory. Relevance realization is playing an important role. And we can see how its getting a—we see how it's getting sort of developed and specified into and connected to other important cognitive processes.

Alright. I think the next important theory we should turn to is Sternberg. So, and this is because you can see Sternberg's work (writes Sternberg) running throughout the history. Robert Sternberg's work—running through the history of the psychology of wisdom. Robert Sternberg basically really gets this off the ground with his pivotal work, not only in his own theories. But, the title this work he's done in putting together anthologies, various anthologies on wisdom or related anthologies on foolishness, Why Smart People Can Be So Stupid as one of the best anthologies on the psychology of foolishness I've seen right.

He is also been tireless in trying to connect the psychology of wisdom to pedagogy. He gets—again, something that is important and central, and we see it crucially in the ancient theories of wisdom. It's not so clearly present in the current psychological theories, but the deep connection between wisdom and teaching that's, of course, clearly the case in Socrates, it's clearly the case in Jesus of Nazareth. It's clearly the case in Buddhism that they're, like in the work of the Buddha, that there's a deep connection between wisdom and education. And so he's been very tireless, not only sort of theoretically pointing out that connection, but trying to work out, if you'll allow me, I mean, this word in a complimentary sense, trying to engineer some psychotechnology, sets of practices for how to bring the cultivation of wisdom into the educational domain.

So, and so for many reasons, Sternberg is a pivotal figure in the wisdom ind—the wisdom. I was going to call it the wisdom industry. That sounds like an industry for producing wisdom. In the community of people who are endeavoring to come up with a psychological cognitive scientific, even neuroscientific theory of wisdom. There are some people who are pursuing this. Meeks and Jeste are one. Other people are pursuing the neuroscientific aspects, but I'm not going to go into that in great detail right now. I'm trying to concentrate on the psychological theories, precisely because they are the ones that are most directly accessible and relevant to trying to respond to the meaning crisis.

A Balance Theory Of Wisdom

So in 1998, Sternberg, he had an earlier theory where he was talking and he's come back to this many times. He has a book where he tries to talk about the relationships between intelligence, wisdom, and creativity. I'm trying to follow that up in my own way, trying to show you the relationships between the intelligence, rationality, wisdom, insight, et cetera. So definitely influenced by Sternberg in that way, but he then came up with a more—I don't—I want to be complimentary of the newer theory without being completely dismissive of the older. I would say the newer theory is sort of more coherent, more tightly integrated, more explicated. So in 1998, he came up with what he's called and maintained a balance theory of wisdom. That's actually the title of the 1998 article, A Balance Theory Of Wisdom. So the notion of balance (writes Balance beside Sternberg) is going to play a crucial role in this theory.

Now Sternberg starts by talking about sophia and phronesis and episteme, which is at the core of epistemological—that's what I would call propositional knowledge. He calls it scientific understanding. He quickly drops that as not being particularly relevant to wisdom, not because knowledge is unimportant. Because everybody knows the centrality of knowledge to wisdom. That's why we're spending so much time on getting knowledge in this course, but everybody pretty much also understands that wisdom is something above and beyond scientific, theoretical propositional knowledge. Okay. So that's sort of easily understandable.

He also, like I said, he invokes sophia and talks about it sort of in connection with contemplation, phronesis and practical wisdom. He zeroes in like Schwartz and Sharpe on phronesis. I think that's, again, a little bit too much of a neglect of the important role of sophia. He also draws on Polanyi's idea of tacit knowledge. Remember we talked about that when we talked about subsidiary awareness? And he talks about the tacit knowledge having to do with our procedural abilities. It's relevant to attaining goals. It's not explicitly taught, we experience it intuitively, so he's invoking all kinds of important aspects about implicit learning, intuition and procedural knowing.

I think that's good. I think he needs to also add to that techne. What are some important psychotechnologies? Especially since I can, I think, in fairness, say that he is trying to engineer such psychotechnologies in his pedagogical endeavors. I also think he needs to try to do what Aristotle did, which is integrated how phronesis, which is largely happening in an implicit intuitive sort of S1 kind of fashion is integrated with sophia, which can have a more reflective, perhaps a more S2 aspect to it.

All right. That being said, what's the core theory? Well, the idea is we, and this is important because it's just sort of directly invoked, right? He invoked—the tacit knowledge is also... It's used as a way of— he starts talking about it as tacit understanding. So the tacit knowing, the tacit—the implicit learning, it is also a way in which Sternberg tries to invoke the capacity for understanding.

Now that isn't very well explicated in the account. I'm thinking. I'm trying, I'm speculating that what I think he's trying to get at is that the machinery by which we sort of grasp the significance of our knowledge and use it to directly and intuitively cope with the world is a significant component of understanding. So I think that's why the shift is there. He then talks and the way, the reason why I want to invoke that is because the, what the tacit understanding is doing it's again, so pregnant with aspects of relevance realization, because he talks about the understanding, guiding our ability to adapt to—listen to that language, to adapt to situations, to shape them. And that doesn't necessarily mean physical. It can mean how we construe them, how we formulate our problems and the selection of environments, the selection, the moving around the exploring or exploiting. This is all very much doing with relevance realization. He talks about these abilities are needed to deal with practical problems.

This is why he's emphasizing wisdom. Not as the same thing as theoretical knowledge, he's picking up on the same point that Monika Ardelt did. But he said these practical problems, quote, are unformalized or in need of—sorry, I misquoted. And that misquotation was an important mistake. These problems are unformulated, much more relevant to problem formulation or unformulated or in need of reformulation. And so he's invoking problem formulation here. He's, of course, with the notion of reformulation, he's invoking the notion of insight. And so we can see, again, the relevance realization machinery being invoked.

So his theory quote involves—sorry, his theory involves quote views. Let me start that again. His theory, quote, views wisdom as inherent in the interaction between an individual at a situational context. It's inherently transjective. It's about fitting. In fact, he then goes on to say wisdom depends on the fit of a wise solution to its context. So notice the fittedness. All of the language that we've developed is being directly invoked, it's being put at the center of the theory.

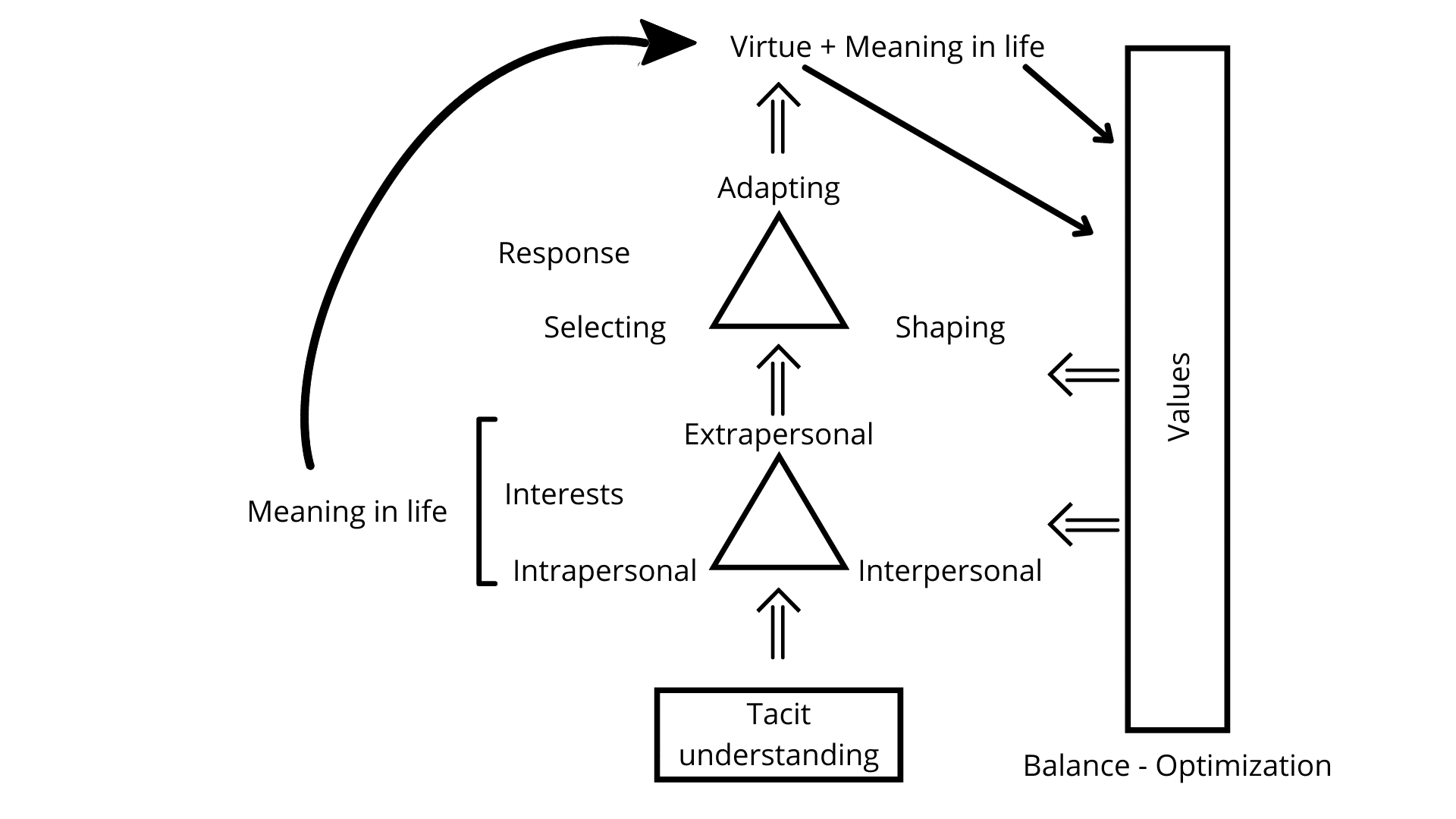

And I'm going to argue that what he is invoking when he's invoking balance is he's invoking optimization (Fig. 4) (writes Balance - Optimization). And I, of course, argued that relevance realization is an optimization theory.

Fig. 4

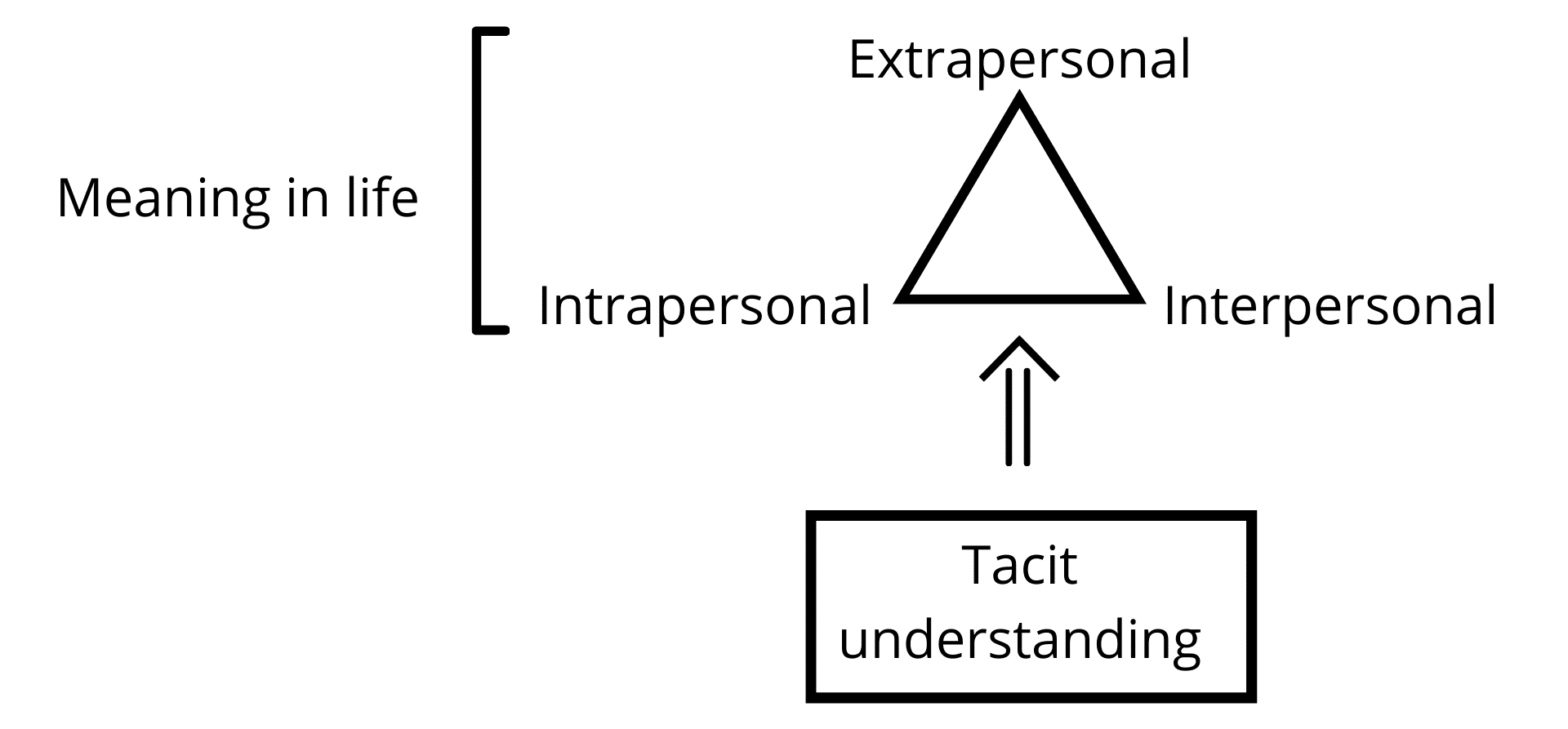

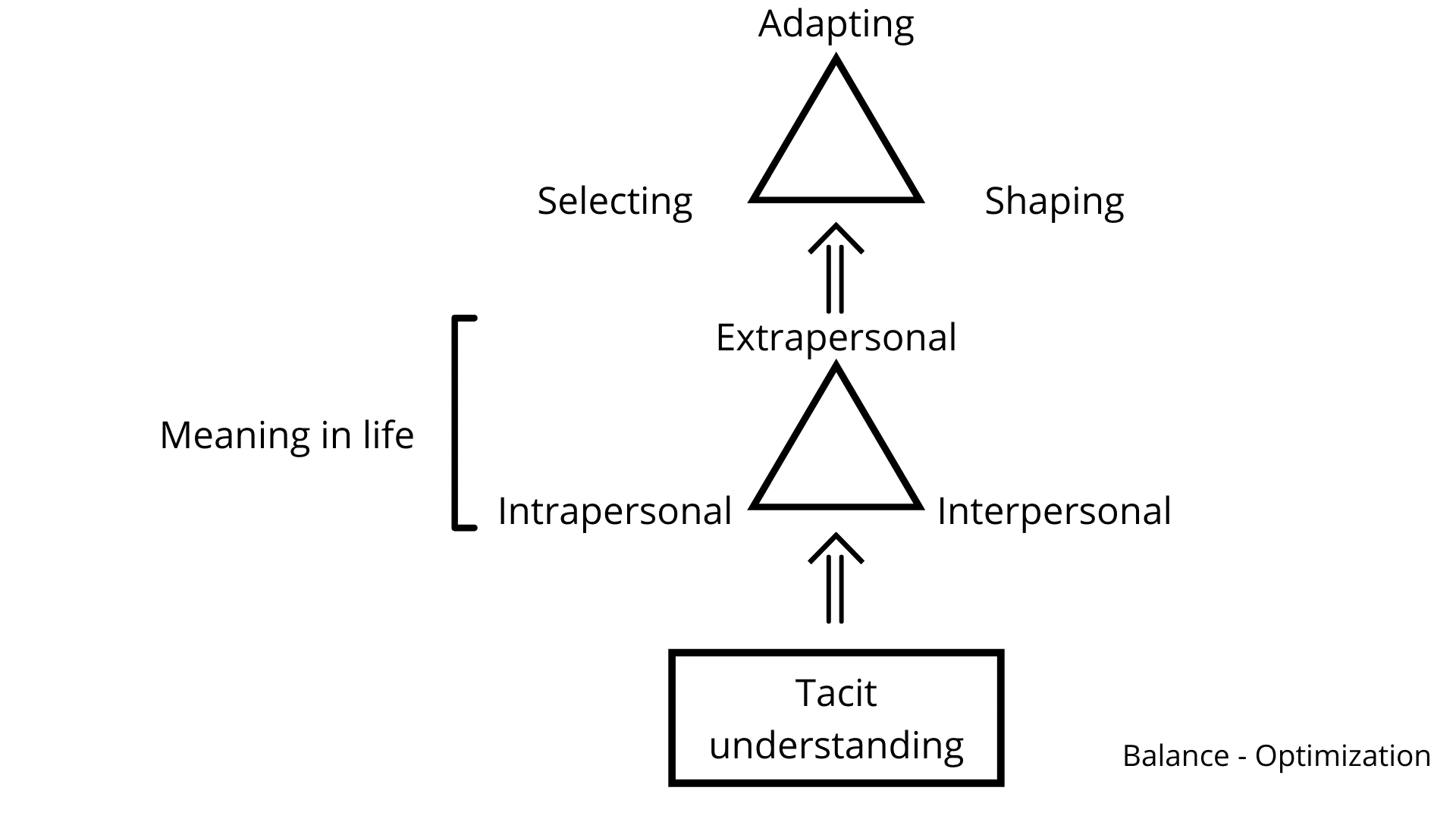

So what's sort of beautiful about the theory is he gives a schematic diagram of it and I'll draw this for you. So here's our tacit understanding (draws a box and writes Tacit understanding inside) that's that implicit processing, et cetera. Remember, we talked about that so much in connection with flow?

And what's happening is it is dealing with trying to balance your interests (Fig. 5a) (draws a triangle above Tacit understanding). Balance your interest. What you're interested in, what you find salient, important. And he talks about three kinds. There's the intrapersonal, the interpersonal and the extrapersonal. So this of course is interest between people (writes Interpersonal at the right corner of the triangle). This is interest within a person (writes Intrapersonal at the left corner of the triangle). So you can think of Plato here trying to get your various centers and what they're interested in coordinated together. And extrapersonal (writes Extrapersonal at the top corner of the triangle), having to do... I think this is ultimately how you're connected to yourself (indicates Intrapersonal), how you're connected to other people (indicates Interpersonal) and how you're connected to the world (indicates Extrapersonal). I think he's invoking, at least implicitly, the three dimensions of connectedness that go into meaning in life. And so, I think, at least implicitly, we could make a clear argument here that he's trying to connect wisdom to meaning in life (draws a bracket on the left and writes Meaning in life).

Fig. 5a

And that this capacity (indicates Tacit understanding) for sort of zeroing in on relevant information is playing an important role in that. And the reason why I say that is because (Fig. 5b) (draws an arrow pointing up from Extrapersonal). It's not clear to me why the arrows only go one way. It seems to me that I—well, this is a criticism I would make. I think the arrows should go both ways because there's also going to be feedback. But anyways, they feed forward to the three things (draws a triangle above the second arrow) that are clearly I would argue are, which is the adapting (writes Adapting at the top of the second triangle), the shaping (writes Shaping at the right corner of the second triangle), and the selecting (writes Selecting at the left corner of the second triangle).

Fig. 5b

I'll come back to that (indicates Balance - Optimization and erases it on the board) notion. The triangles are meant to indicate balance. And I've tried to indicate to you that,I think, I'll put that down here and we'll come back to it. That balance has to do with optimization (writes Balance - Optimization).

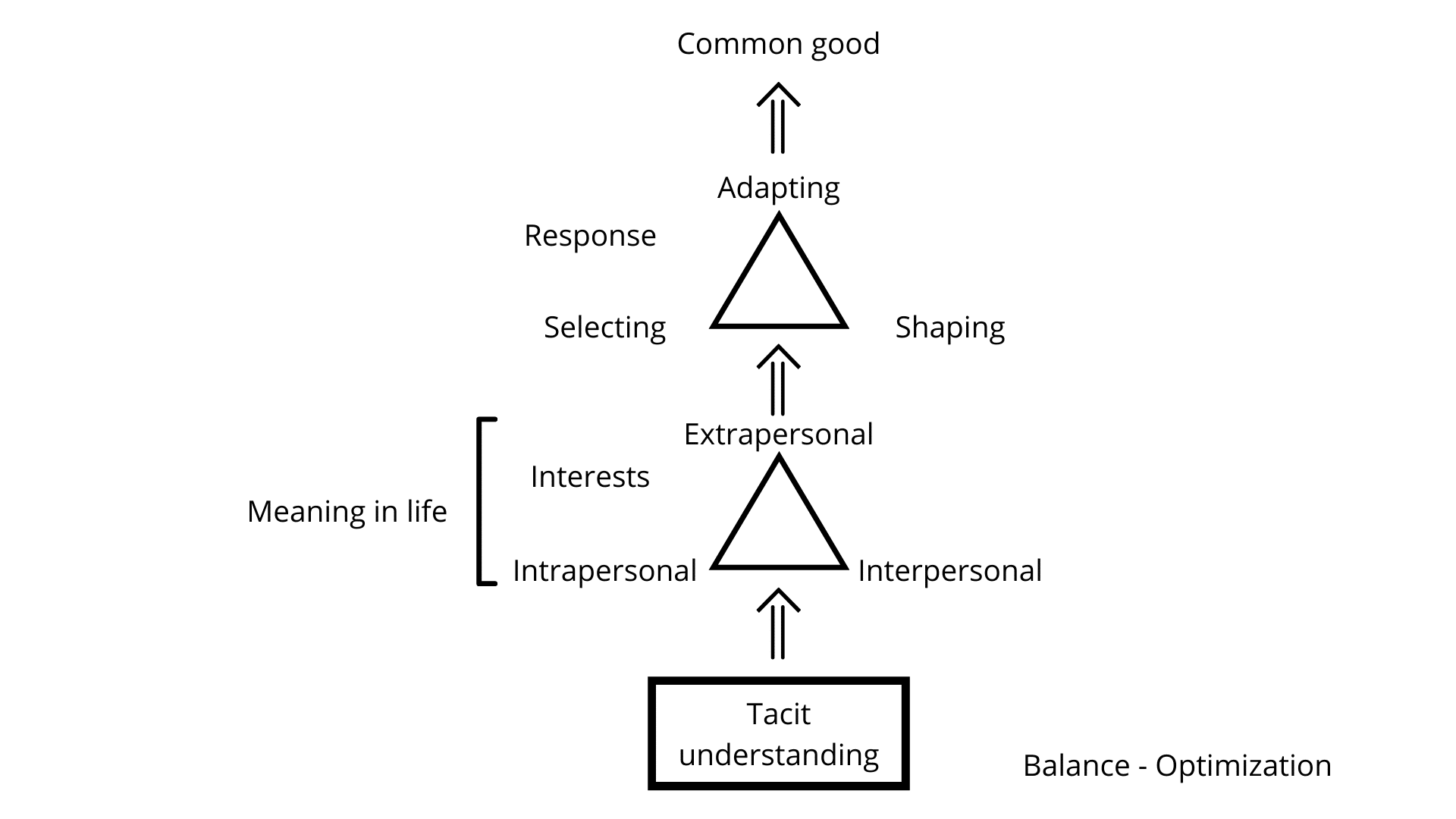

Okay. So what's going on here is this is a balance of your response to the environmental context. So this is balancing your interests (indicates the lower triangle and writes Interests) and this is balancing your response (writes Response beside the second triangle). Like I said, that's (indicates the upper triangle) pretty clear of our relevance realization stuff.

This then is directed towards, he argues the common good (Fig. 5c) (draws an arrow above the upper triangle). Here again is where I have to step aside (writes Common good) from the value he's articulating and the theory he is generating. I agree, especially within a liberal democratic framework, a framework deeply influenced by Christianity, that the common good is an overarching value for us. I'm not sure that that is going to be universally shared by all people who I think can reasonably be deemed wise individuals.

Fig. 5c

So if you're in a culture, that's—what this means, maybe you have to bend this (indicates Common good) so much, then it's then trivial. It doesn't mean—maybe it doesn't mean common in the sense of shared by everyone. It might be, you know, you're in some sort of hierarchical, feudal society and the common good isn't that everybody equally benefits from it. It might be more that, you know, everybody is working well together, some sort of justification like that.

I'm not trying to justify a hierarchical society or anything like that. I want you clearly to understand. I think this (indicates Common good) is an important value. I'm just concerned here that Sternberg is being anachronistic here and he's using one of our central values and attributing it to every person who has been wise? I'm not, I'm not sure. I mean, I think you could make a case that that's clearly the case in Jesus or the Buddha. I'm not sure that it's the case for Marcus Aurelius and all of the Stoics. It's clearly not the case for Epictetus. So I'm hesitant about putting that up there.

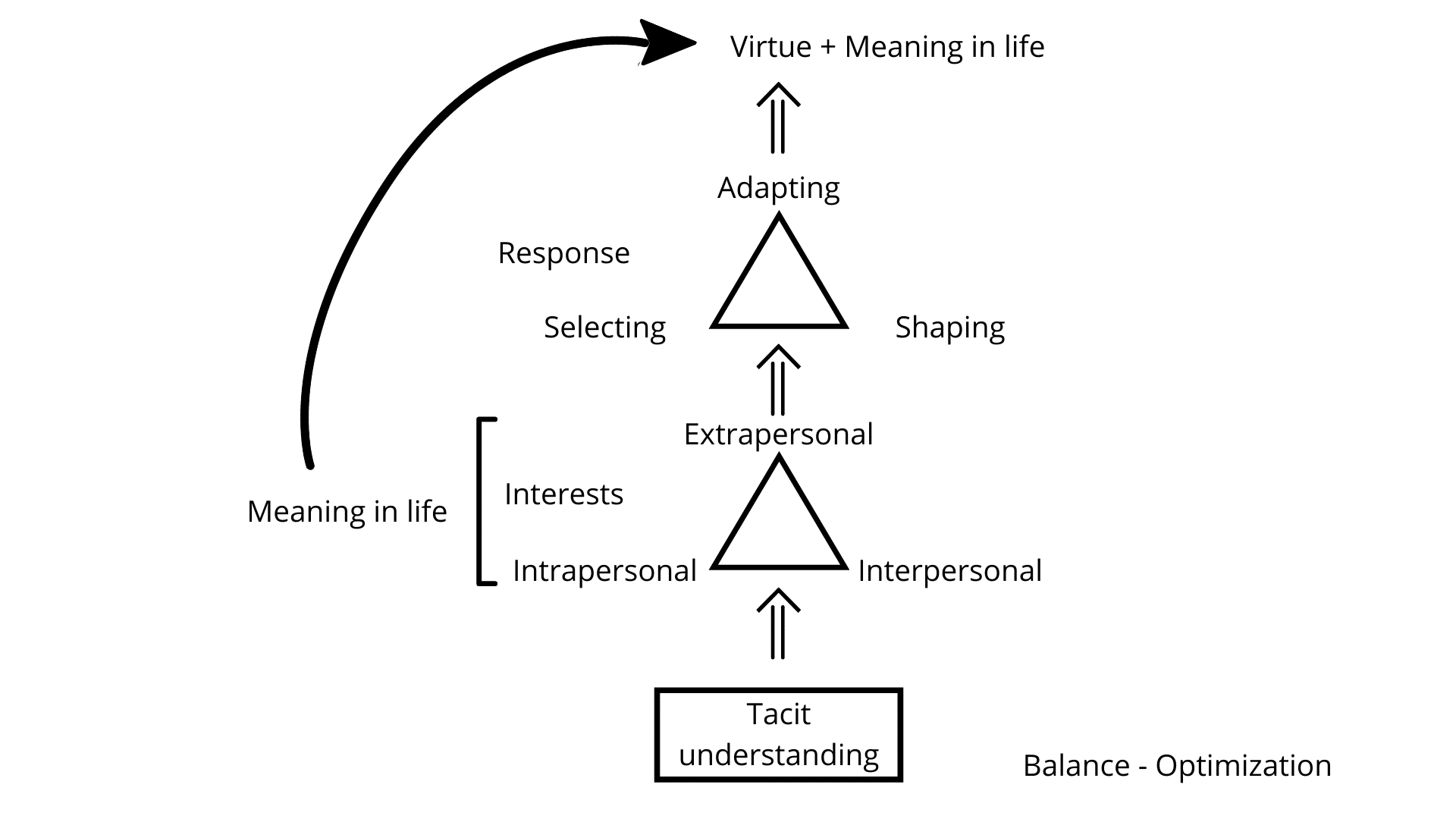

I'm going to advise that there's something I think more, more broadly comprehen—I think the things that we should put up here (erases Common good) are things that there's already a consensus on a broader notion of virtue. Oh, sorry. That really makes it sound like I'm making an emphasis here that we're really concerned with is virtue (Fig. 5d) (writes Virtue above the upper triangle). Right? And because of this (draws an arrow from Meaning in life to Virtue), I think, and meaning in life (writes + Meaning in life).

Fig. 5d

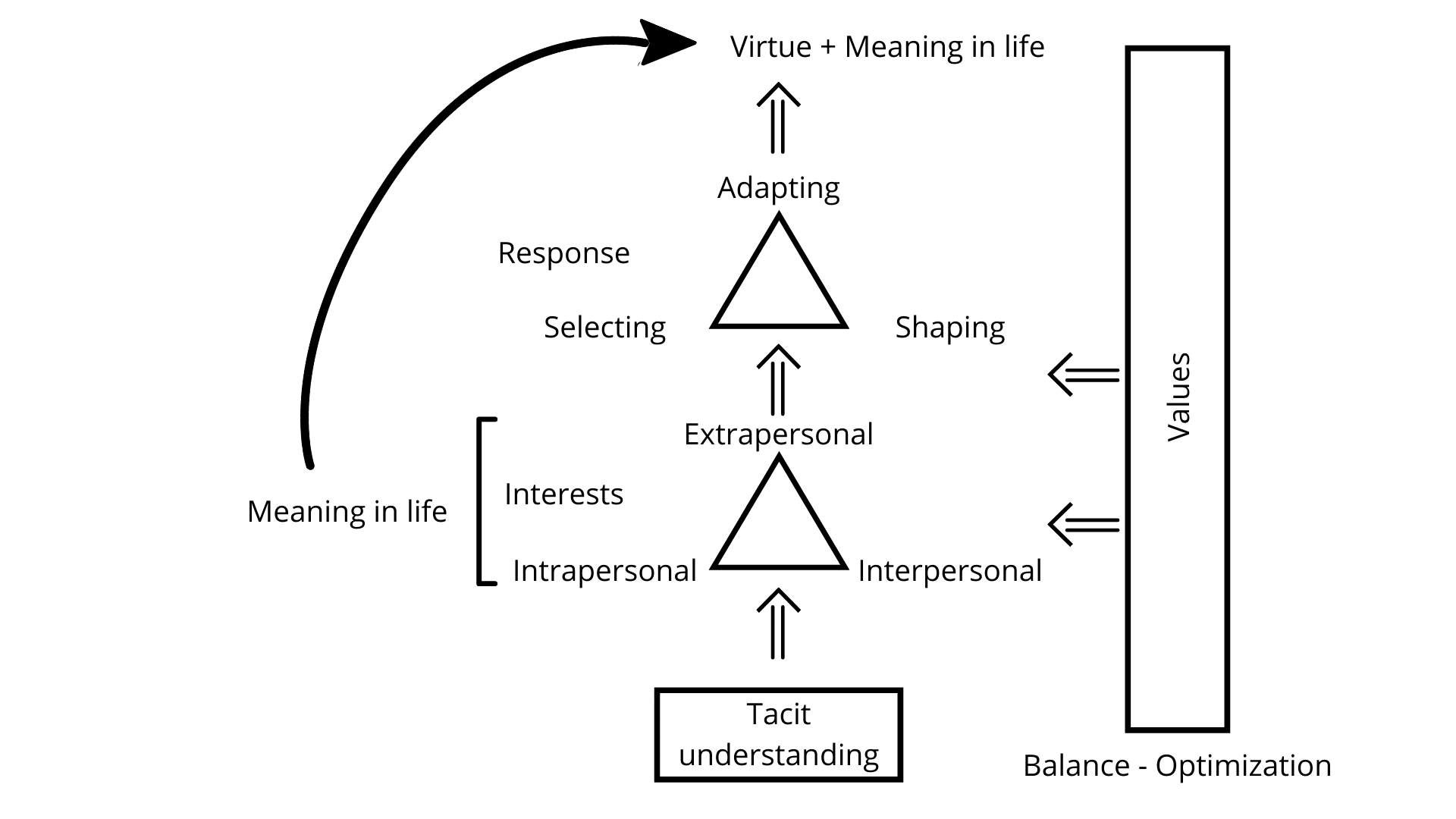

Okay. I have changed (indicates Virtue + Meaning in life) that is not in his model. I have changed it because of, again, I'm worried that his particular term is, anachronistic and idiosyncratic to our particular historical cultural context. It's important to also note that, running alongside of this (draws a rectangle to the right) is values (Fig. 5e) (writes Values inside the rectangle) and then arrows that are kind of indeterminately pointing (draws two arrows from Values pointing to the left).

Fig. 5e

So trying to interpret what that means is something like, the wise person is being constrained by values. What those values are are not clear. Again, is it that we're talking about things like meaning in life and the virtues (Fig. 5f) (draws an arrow from Meaning in life to Values and another arrow from Virtues to Values)? Perhaps.

Fig. 5f

So another criticism I have is that this part of the theory (indicates the part where Values are located), this part of the diagram, the way it's operating is unclear. It might be something as basic as the wise person is working normatively. They're trying to get the best. And then this (indicates the Values) is not that interesting a claim because wisdom is itself a normative notion. And therefore the fact that the wise person is being governed by normativity is almost definitional. If it means something specific like the wise person has a specific set of values that needs to be explicated and defended. So I don't know quite what to do with that. So I have to sort of leave it somewhat inert.

What I would argue, and I think what these triangles indicate and what the language indicates is that the balance is used to adapt to shape and select environments. And what is this balance? He argues that something like Piaget's equilibration between assimilation and accommodation. He argues that it's a balance between coping with novelty and proceduralization.

You see what he's doing, what the balance here is? It's balance that is directly invoking a lot of the machinery we've talked about relevance realization, and he's clearly not invoking sort of a spatial balancing. He's invoking optimization. He's invoking optimization.

So I think this theory is also a theory that is deeply integratable with a lot of the material we've been discussing. Relevance realization is playing a key role in terms of the balancing and this (indicates the upper triangle) process here also down here (indicates Tacit understanding) at the level of grasping the significance, at least intuitively of our knowledge and the patterns we picked up from the environment. There's deep connections to, or at least there's a real potential in Sternberg's theory for making deep connections to meaning in life (taps the lower triangle). Because as I said, I think this has played clearly how you connect to yourself (indicates Intrapersonal), how do you connect to others (indicates Interpersonal), how do you connect to the world (indicates Extrapersonal). Right? There's important possible connections, possibly (indicates Values)—I'm unsure between this (indicates Values) and virtue and meaning in life. So this is all very good. And like I said, overall, this is clearly a dynamic optimization and it's invoking something very much like relevance realization.

All right. What are some of (the) criticism? Well, I'll leave that on the board for now. What are some of the criticisms of Sternberg? This is still in the end, a product theory. It's not a process theory. It doesn't make the sort of, I mean, this (indicates Tacit understanding) avoids equating wisdom with expertise and that's a powerful advantage of this theory, but there, like I said, this domain, the values unexplicated, it could either be somewhat trivial, because it's almost tautological that the wise person is acting according to normative standards, or it could be a much more controversial claim that specific values are involved. I don't know. I've already told you (indicates Virtue + Meaning in life) I don't think that the common good is the goal of all wise people that see seems anachronistic to me in an important way.

The theory could clearly be improved by getting clear about the nature of tacit implicit learning. Getting clearer about optimization, getting clearer about relevance realization, getting clearer about how relevance realization connects to meaning in life. So all of those things would be developed if one started to develop a process theory and not just a product theory.

So Sternberg needs an independent theory of foolishness. Now he has a theory of foolishness, but it's not independent. His theory of foolishness is basically foolishness is an imbalance in these things. So what foolishness is, is basically a lack of wisdom. And again, while that's definitionally the case, what you need is an independently constructed theory of wisdom—sorry, a theory of foolishness. You need a theory of foolishness that takes in hand the centrality of seeing through illusion and into reality, that has an independent account of how we're self-deceptive, how we're self-destructive, how that operates, how that unfolds, because we see that in many of the ancient wisdom theories and how we can ameliorate that. So I think that that is missing in a central way from Sternberg's work.

Okay. So I think in the end, what I want to do is try and draw all of these together. I've tried to indicate important points of improvement. One theory, with respect to the other relative strengths and weaknesses. I've also tried to indicate powerful points of convergence and connection to the ideas of relevance realization that we've been developing in this course because that's part of the big possibility diagram. To show how the machinery of relevance realization can help to explain what it is to be wise and help to explain, as I'm going to argue, what it is to become wise, to give a processing theory.

So we want to take that up in the next account. And I'm somewhat hesitant about that. Because you know, I'm sort of okay with, you know, offering you proposals of—well, I'm not, I mean, I'm very cautious about proposals, about consciousness and other things like that, but, you know, we've got proposals about higher states of consciousness and insight and that. And I've tried to make arguments for that, and I'm going to make an argument that I have made with Leo Ferraro about wisdom. But there—it's something —it borders on hubristic to talk about this in that way, but I'm going to try and draw on this and at least show you a plausible way in which we can draw all of this material together with the theory of relevance realization and come up with an account of wisdom.

And then, I think, also subject that theory, at least the version that was published in 2013 to some important criticisms. And then hopefully then be in a place where we can fold it back into the connections between wisdom, the cultivation of wisdom, the cultivation of meaning in life, the cultivation, the pursuit—are these the right verbs?—of enlightenment. How these are all connected and how that can be situated into the larger project of awakening from the meaning crisis.

Thank you very much for your time and attention.

- END -

Episode 44 Notes

To keep this site running, we are an Amazon Associate where we earn from qualifying purchases

Herbert Simon

Herbert Alexander Simon was an American economist, political scientist and cognitive psychologist, whose primary research interest was decision-making within organizations and is best known for the theories of "bounded rationality" and "satisficing".

Bounded Rationality

Bounded rationality is the idea that rationality is limited when individuals make decisions. In other words, humans' "...preferences are determined by changes in outcomes relative to a certain reference level..." as stated by Esther-Mirjam Sent (2018).

Leo Ferraro

Publication: Relevance, Meaning and the Cognitive Science of Wisdom

Susan Wolf

Susan Rose Wolf is an American moral philosopher and philosopher of action who is currently the Edna J. Koury Professor of Philosophy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

L. A. Paul

Laurie Ann Paul is a professor of philosophy and cognitive science at Yale University. She previously taught at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the University of Arizona. She is best known for her research on the counterfactual analysis of causation and the concept of “transformative experience.”

Robert J Sternberg

Robert J. Sternberg (born December 8, 1949) is an American psychologist and psychometrician. He is Professor of Human Development at Cornell University.

Book Mentioned:

Wisdom: Its Nature, Origins, and Development - Buy Here

A Handbook Of Wisdom: Psychological Perspectives - Buy Here

The Cambridge Handbook of Wisdom - Buy Here

Why Smart People Can Be So Stupid - Buy Here

Applying Wisdom To Contemporary World Problems - Buy Here

Teaching For Wisdom, Intelligence, Creativity, and Success - Buy Here

Wisdom, Intelligence, And Creativity Synthesized - Buy Here

Article Mentioned: A Balance Theory Of Wisdom

Dilip V. Jeste

Dilip V. Jeste, M.D. is an American geriatric neuropsychiatrist, who specializes in successful aging as well as schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders in older adults.

Sophia

Sophia is a central idea in Hellenistic philosophy and religion, Platonism, Gnosticism and Christian theology.

Phronesis

Phronesis is an ancient Greek word for a type of wisdom or intelligence relevant to practical action, implying both good judgement and excellence of character and habits.

Episteme

Episteme is a philosophical term that refers to a principled system of understanding; scientific knowledge.

Michael Polanyi

Michael Polanyi was a Hungarian-British polymath, who made important theoretical contributions to physical chemistry, economics, and philosophy.

Tacit knowledge

Tacit knowledge or implicit knowledge—as opposed to formal, codified or explicit knowledge—is knowledge that is difficult to express or extract, and thus more difficult to transfer to others by means of writing it down or verbalizing it. This can include personal wisdom, experience, insight, and intuition.

Other helpful resources about this episode:

Notes on Bevry

Additional Notes on Bevry